#Illustration

#Books

Three illustrators who contributed to artbooks ‘The Shanghairen’ and ‘The Beijingren’ answer the above question Read More

Only three years ago, the future of the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, China’s preeminent private contemporary art museum, looked hazy. The museum was established by Belgian collectors Guy and Myriam Ullens in 2007 in Beijing’s 798 art district, helping to reinvigorate what had previously been a loose collection of artist residences and small galleries under constant threat of eviction into a thriving hub of commercial and nonprofit art spaces. After nearly a decade promoting cultural exchange through exhibitions and programming, on June 30, 2016 it was announced that the Ullens were looking to sell UCCA, news that jolted the art world. As Randian wrote at the time: “the stunning news means that clouds are hanging over the future of the institution, widely regarded as the most important contemporary art institution in the country.”

UCCA’s renovated facade (Twitter)

Relief from this uncertainty came almost a year and a half later, when it was announced in October 2017 that a pool of investors would step in to fill the role previously held by the Ullens, with UCCA persisting under the stewardship of director Philip Tinari. The museum’s financial future secured, Tinari promptly launched a series of sweeping renovations, which were first partially glimpsed in a monumental retrospective for Beijing artist Xu Bing last year.

But the full scope of UCCA’s rebirth was unveiled earlier this month to coincide with what is arguably its highest-profile exhibition to date: Birth of a Genius, an array of 103 works by Pablo Picasso, mostly from the first three decades of his career. Despite the Spanish artist’s profile, his history of being exhibited in China is remarkably short. According to an essay by art historian Wu Xueshan accompanying the exhibition’s catalog, the first time a work by Picasso was shown in China was at the very birth of the nation-state as it exists today, on October 2, 1949. Having been heartened by Picasso’s decision to join the French Communist Party five years prior, early PRC leadership adopted the artist’s Dove of Peace as an emblem of international solidarity:

In April 1949, the Chinese delegation to the World Peace Council in Prague saw Picasso’s dove of peace, and later, this dove flew to Beijing. On 2 October 1949, the Chinese Conference for the Protection of World Peace was held in Beijing, with major figures like Zhu De, Gao Gang, Chen Yi, Lin Boqu, Dong Biwu, Guo Moruo, and Deng Xiaoping in attendance. In the 3 October edition of People’s Daily, a report stated that “the decorations at the meeting site were stately and refined, and hanging from the center of the dais was Picasso’s famous work — a dove representing world peace.” The next day, People’s Daily published another article about the conference that described the images above the dais: “Portraits of Stalin and Mao Zedong hung above the stage, while Picasso’s famous dove emanated a radiant light of peace.” In other words, Picasso’s dove was featured alongside portraits of Stalin and Mao. Naturally, this “famous painting” was probably a copy based on the promotional materials for the World Peace Council.

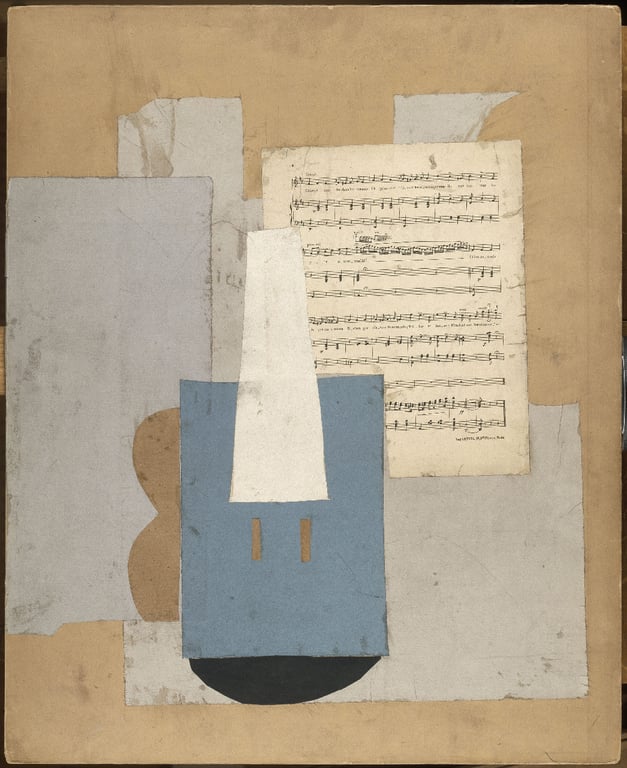

Violin and Music Sheets, Paris, autumn 1912 (Musée national Picasso-Paris)

It would be a long time before original, non-shanzhai Picassos would make their way to China. Picasso was first properly exhibited ten years after his death, in 1983, when 33 of his works were shown at Beijing’s State-run National Art Museum of China (NAMOC). 62 works were exhibited at the Shanghai Expo in 2010, and NAMOC included 100 Picasso prints in a 2014 exhibition, but according to Tinari, Birth of a Genius represents the first time the master’s works have been selected and curated with a specifically Chinese audience in mind. “Birth of a Genius is not a simple touring exhibition, but an exhibition tailored for UCCA and the Chinese audience,” Tinari said at an opening press conference:

“We believe that Picasso’s story is closely related to today’s Chinese audience, as the unique individuals here continue to address the challenges of creativity, originality and innovation.”

Birth of a Genius is a collaboration between UCCA and Musée national Picasso-Paris, and has been touted as “a significant contribution to the bilateral cultural dialogue between China and France” by such high-ranking luminaries as French president Emmanuel Macron, Prime Minister Edouard Philippe, and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang. RADII caught up with UCCA director Tinari on the eve of the exhibition’s record-breaking opening to discuss its significance as a benchmark of bilateral cultural diplomacy, UCCA’s role within China’s contemporary art landscape, and where the institution’s momentum will be directed in the near future.

French President Emmanuel Macron meets with artist Xu Bing and UCCA director Philip Tinari

RADII: Birth of a Genius is the largest show of work by Picasso ever mounted in China, and the press release says that it “grows out of a recognition of the importance of cultural and artistic exchange between France and China at the highest levels.” What level are we talking about here?

Philip Tinari: It was actually president-to-president, in terms of deciding and making a priority of, specifically, more high-level exhibitions traveling between China and France. That’s a cultural policy priority that was first voiced during Macron’s visit in 2018, when he actually came to UCCA. It continued in June of 2018 when Edouard Philippe, the Prime Minister, came, then in March of 2019 when Xi was in Paris. At their joint press conference at the end of that meeting they voiced that again — in fact, Macron listed this exhibition as an example of that.

And then finally, when the French Foreign Minister came for the Belt and Road Forum [in April/May 2019], at his meeting with his Chinese counterpart, he raised the very key issue that it’s great to have this policy directive, but you then have to go about getting this work into the country. We’re an accredited museum and a non-profit, but there’s the challenge of dealing with customs. Getting a waiver of the import duty for this noncommercial exhibition purpose is what allowed us to organize the show.

What is your plan or hope to facilitate this exchange in the other direction by exhibiting Chinese artists in France?

We have lots of ideas in that regard. Nothing on the books right now. But to give one example — this is not exactly a collaboration, but Cao Fei is a great Chinese artist who’s having a major show here in the Fall of 2020, and she’s just opened a show at the Centre Pompidou [a few weeks ago]. So at least on that level, of the kinds of artists that we’re interested in, that kind of interaction, there’s a lot going on. We’d love to send our shows to French museums, so we’ll see if there are those kinds of opportunities.

This exhibition is also a full unveiling of a major series of structural renovations for UCCA. How long has the renovation been in the works and what are the major changes?

Basically, UCCA restructured in late 2017, so 2018 was very much a transition and construction kind of year. 2019 is a rollout sort of year. We finished the facade in January, and we’ve been phasing everything in over the last six months. The landscape, the cafe just opened today, the store just opened today, there’s a Shanghai Tang store here, and then kids’ education on the second floor of the red building, and our offices on three and four. That’s the transformation.

You opened a satellite space last year, UCCA Dune in the remote coastal enclave of Aranya. What is the plan for that space and how does it tie in with the program in Beijing?

UCCA Dune, which we operate as part of Aranya’s community, is a couple of things. It’s an amazing building that we are really lucky to have architectural and curatorial stewardship over. It’s a very distinct — you might even say, challenging — exhibition space, where we organize exhibitions specifically that go with that space, two a year, for a very dedicated group of vacationers and tourists, people who are coming through that place. But for us, operationally, it’s also an example of how it might work for us to be operating across multiple sites. We actually program Dune from Beijing, and execute there, but the partnership with Aranya, and the way we are curating for non-Beijing sites from Beijing, are maybe relevant to future developments.

UCCA Dune

What else is on the horizon for UCCA that you’re excited about?

The Fall show is Matthew Barney, one of the highlights of the year. It’s an amazing show, a singular body of work that Barney developed in the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho, where he comes from. It’s a film, it’s sculptures, it’s etchings, it’s kind of a Gesamtkunstwerk if you will. So that’s going to take over our Great Hall from late September to mid-December. And he’s an artist that I’ve always been very passionate about, but also who had a huge influence on the Chinese art scene in the ’90s, as it was first internationalizing. So that’s the Fall show, and then we’ve got a number of other things in the works for next year.

“There’s always been a real desire to use art as a space to convene global conversations.”

Speaking of diplomatic or governmental support — is there any official interest from the US side in that show? Are they supporting in any way?

We’ve shown a number of American artists over the years, and there’s always a willingness to engage. The US government is not necessarily resourced to be supporting exhibitions happening in foreign countries. But at the same time, we didn’t receive financial support for this [Picasso] show from France, either, and we won’t require that level of support governmentally to realize the show of Barney.

We always do have an eye to how these kinds of moments can create chances for conversation, dialogue, understanding between China and different parts of the world. That’s always been part of UCCA’s mission since the beginning, one thing that makes us different from all these other private museums in China, is that we were founded in the very lead-up to the [2008 Summer] Olympics by a passionate European who wanted to put Chinese art in an international context, and vice versa. And we’ve stayed true to that, even as we’ve become much more locally grounded over the years. I think there’s always been this real desire to use art as a space to convene global conversations.

—

Find full info on Picasso — Birth of a Genius on UCCA’s website

You might also like:

#Illustration

#Books

Three illustrators who contributed to artbooks ‘The Shanghairen’ and ‘The Beijingren’ answer the above question Read More