How German Settlers in China Created One of the World’s Most Consumed Beers

In the seaside city of Qingdao, the German-founded Tsingtao brewery has withstood a century of turbulence to produce one of the world's most consumed beers

There’s only one thing powerful enough to bring over six million tourists to China during the peak of the mainland’s most sweltering months — beer. More specifically, the biggest beer festival in continental Asia.

Fittingly dubbed the “Asian Oktoberfest,” the Qingdao Beer Festival boasts over 1,300 types of beer, from over 30 different countries and regions. This booze-filled maze of tents, live music and belly-baring, drunken antics lasts the entirety of a month in the seaside city that gives it its name.

Beer lovers will have great chance to revel in the ongoing 29th Qingdao International Beer Festival. Hailed as Asia's Oktoberfest, the Qingdao International Beer Festival is the largest of its kind in Asia and one of China's biggest tourism events. pic.twitter.com/0Zs21vjpnQ

— Qingdao, China (@loveqingdao) July 28, 2019

But why Qingdao? Here’s a look at the surprising story of how this northeastern Chinese city became synonymous with beer, with a little help from Germany.

The Birth of the Brew

In 1891, recognizing Qingdao’s unique coastal location, leaders during the late Qing Dynasty turned the city into a defense base against naval attack. But European colonists had other plans for the small Chinese town. Thirsty for land and control, German naval forces soon seized the coastal backwaters of Jiaozhou Bay, in what is now known as Qingdao. The precarious Qing Dynasty regime was unable to defend itself, and Qingdao was swiftly refitted to be the administrative center of Germany’s newest colonial concession.

The Germans would soon become thirsty for something a bit more refreshing than new land. After the occupation, settlers realized that there was one integral thing missing in their new home — a brewery. In 1903, the Germania Brauerei was founded by Anglo-German Brewery Co. Ltd.

A3. The Tsingtao brewery and museum in Qingdao, China. Not just a history of the brewery, it was a great history of the evolution of modern China from the European colonial period and imported German brewers to right now with sleek, stainless steel machines #foodtravelchat pic.twitter.com/2txe5bYZb0

— Gorkamorka (@beekeasy) May 24, 2018

The facility’s first beer, served in 1904, was a German-style pilsner made according to the Reinheitsgeobot, a beer “purity law” originating in Bavaria. Beers made in accordance are crafted using only water, hops and barley so as to ensure what Bavarians felt was the purest production.

These expat brewers adapted to their environment, sourcing mineral water from the nearby Laoshan spring. Thus, from a purist German brewing tradition, the original Tsingtao Beer was born.

Changing Hands

The start of World War I quickly brewed up a storm for Germans living in Qingdao, who were ousted by the Japanese Imperial Army.

By 1916, Germania Brauerei had been liquidated and sold to Japanese brewery Dai-Nippon, which itself would eventually split into the producers of two other famous Asian beers, Asahi and Sapporo. Qingdao’s brewery was then passed from the Japanese invaders to the Chinese nationalist government, and when the People’s Republic was founded in 1949, it became a PRC-owned enterprise. It was finally privatized in 1990 and merged with three other Qingdao-based breweries, to re-emerge as the enterprise we know it as today.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BnYzGt0B8_O/

A note on the spelling discrepancies here: “Tsingtao,” the name plastered on every single beer bottle, comes from the old Chinese postal romanization (largely similar to the Wade-Giles system) of the city’s Chinese name (青岛), which today is more commonly transcribed in pinyin as “Qingdao.”

Tsingtao Today

While German expatriates did have a hand in the original brewery, it should come as no surprise that Tsingtao beer has gradually soaked up the flavor of the mainland since its privatization.

Beer buffs may scoff at the fact that China’s “quintessential beer” is little more than a light lager, more similar in profile to other notoriously weak Chinese beers than the original German pilsner. But others argue that the formula better complements the Chinese culinary palette, pairing well with the spicy, flavorful foods favored in many provinces.

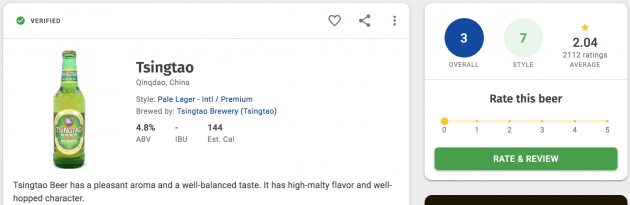

Tsingtao’s score on RateBeer.com

It’s a taste so popular, in fact, that it now accounts for half of China’s national beer exports. Today it produces over 8 million kiloliters of its famous draft brew, and exports to over 70 different countries.

Tsingtao is actually the second-most consumed beer in the world; first is another Chinese beer brand, Snow Beer. But Snow is mostly consumed domestically, and has far less name recognition internationally.

Tsingtao, on the other hand, has evolved into one of the earliest and most widespread symbols of Chinese success (and soft power) abroad. In recent years, the brand has tried to cash in on that household name and crop up on places you might not expect to find it — like the high fashion catwalk. Earlier this year, the beer brand paired up with trendy Chinese streetwear brand NPC to roll out a Tsingtao-themed clothing line at New York Fashion Week.

Related:

Tsingtao’s Influence in Qingdao

In the present day, a large part of Qingdao’s economic development and prosperity has become irrevocably tied to the production of beer. It washes over just about every sector of Qingdao, from the dinner table to the tourism industry and is such a part of everyday life in the city that you can find it being served directly into plastic bags from street corner kegs.

Attractions like the Tsingtao Brewery Museum and the specialty bar in the city’s Liuting International Airport attract thousands of domestic and international tourists annually. But beer tourism isn’t exclusively for those legally allowed to drink — guests of all ages can experience guilt-free inebriation through attractions such as the Tsingtao Brewery Museum’s “drunk room,” which simulates the feeling of a few too many beers.

But no attraction embodies this energy quite like the Qingdao Beer Festival.

First held in 1991 to celebrate the city’s centennial birthday, this festival is Qingdao’s paramount way of commemorating the historic role of beer as an economic and cultural staple in Chinese life. Perhaps that’s why it attracts those six million drinkers from across continental Asia and beyond.

Three hundred drones danced in the air, presenting wonderful scenes related to beer, and celebrating the opening of the 29th Qingdao International Beer Festival in #Qingdao on July 26. pic.twitter.com/PHtIBrS7Rd

— Qingdao, China (@loveqingdao) July 31, 2019

Since German settlers first opened a brewery looking for a taste of home, Tsingtao (and the city it took its name from) has managed to withstand a century of political turbulence and evolve into a symbol of Chinese identity. It’s since cultivated both a loyal following among Chinese consumers and name-brand recognition worldwide, and left an indelible impact on the city in which it originated. Now that’s something to raise a toast to.

Cover image: Thanakrit Gu