Brandstorm is a series in which we feature the most notable fashion, beauty, and retail brands in China. From edgy jewelry designers to coveted influencers, these are some of the industry’s most talked-about names.

Founded by Janny Jingyi Ye, clothing brand Seventyfive draws inspiration from historical Chinese fashion, especially styles from the 1930s, while also upholding sustainability.

Born in Guangzhou and raised in China and Vancouver, the designer expresses her thoughts in a carefree mix of English, Cantonese, and Mandarin, and her sensibilities through fashion, a medium she deems more versatile and universal than language.

Boasting a prestigious academic background (London’s Central Saint Martin and Royal College of Arts), Ye has formed high-profile partnerships with the likes of London Fashion Week and bi-monthly British online magazine Dazed.

While some collections feel like fashion for fashion’s sake, Ye’s work is grounded in innovative research methods and powerfully connects garment production with East Asian history and social issues.

We spoke to Ye to learn more about the brand, which is breaking temporal, cultural, and gender boundaries:

RADII: How was Seventyfive born?

JJY: Seventyfive started at the beginning of the pandemic, […] not a good time to start a brand focused on the materiality and tactility of clothes. That being said, during the pandemic, everything slowed down, and I had a lot of time to refine ideas, learn new skills, explore archives, and think about fashion in ways that I wouldn’t have been able to otherwise.

With Seventyfive, I’ve included a range of new experiences and research methods, and throughout this process, I’ve really grown as a designer.

What inspired your new collection Cardinal?

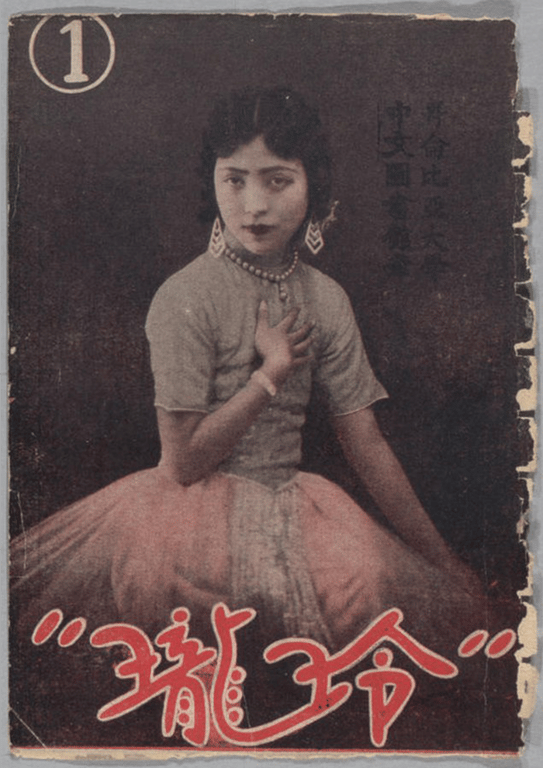

JJY: Cardinal is a continuation of our previous collection, Pomelo, an exploration of the 1930s Chinese women’s magazine Linglong. In Pomelo, we explored the wider spectrum of visuals and ideas shared in the magazine and focused on the reader contributions, which often included photos of themselves.

Linglong was actually very subversive. Lots of women were rejecting marriage [and] relationships and wanted to be single or in life-long companionship with friends.

Cardinal expanded on this premise, focusing on one specific aspect of Linglong: Women practicing androgyny who were regularly discussed and visualized in the magazine. So, the core drive behind Cardinal is Chinese female androgyny in the 1930s.

Why is the collection called Cardinal?

JJY: For this collection, I wanted something that was not too cliche, not too in-your-face, and I remembered that there are certain organisms [who are] born with male and female characteristics, leading to their body being visibly split (gynandromorphy). This happens with butterflies, but also with certain birds, such as cardinals.

I found the cardinal a really striking example, as the body [of mixed sex cardinals] is half beige and half red. I used the name ‘Cardinal’ to reflect on how gender and biological status can be so fluid. That it is not a male-female binary, but rather a spectrum.

Why are you interested in Chinese female androgyny?

JJY: Although the idea of androgyny is not unfamiliar to Chinese audiences — think of things like The Ballad of Mulan and Butterfly Lovers — of Linglong, the topic has been discussed in a more contemporary setting, not as an element of a grand narrative. [Chinese female androgyny] was everyday, mundane, and real.

I started to do more research into the broader spectrum of women practicing androgyny in the 1930s. I followed traces in Linglong to find women around the world who practiced androgyny when it was still a dangerous thing to do. For instance, it was still technically illegal for women to wear trousers in certain countries in the 1930s.

Why is non-European fashion history important to you?

JJY: The vision and perspective of global fashion have always been very Eurocentric. There are many resources to examine fashion from a European point of view, but I feel there is a lack of non-European aesthetics and references; [many] designers and brands are not earnestly engaging with non-European fashion history.

I think many designers with non-European backgrounds and heritage are now trying to engage with reference points, materials, and garment traditions from outside of Europe.

For me, that means a more Asian aesthetic and garment philosophy, meaning the looks, the materials, and how garments can be constructed to last longer — sustainability through sturdiness.

This does not mean Europe will disappear; other brands will continue to reference Europe, and even Linglong discusses European fashion. European fashion is inescapable, but by introducing examples from elsewhere in the world, I hope that the fashion industry can become more inclusive and more diverse.

How do you think fashion relates to social topics such as gender issues?

JJY: I think fashion has been a safe space for a variety of communities to express themselves for some time. This was visible in the 1930s, through our source material, Linglong, with women wearing androgynous looks and complaining about life in a patriarchal society where they were expected just to get married and have children.

Fashion, for those women, was not just an escape, it was them being true to themselves. I am not an expert on gender and sexuality, but the fashion and aesthetic codes we live by have been taught to us from a young age.

Many people may ignore fashion and aesthetics, considering them trivial or frivolous. But clothes are one of the first things you notice about people, how you evaluate and understand them, and they are some of the easiest codes to break, to play with.

Why did you choose to launch your collections as multimedia projects, including videos and zines?

JJY: While Cardinal is a collection considering gender and androgyny, it is also about China, Chineseness, the Chinese diaspora, and being East Asian.

I hope that through fashion and multimedia projects, I can continue to give a voice to East Asian people, people from the modern-day and the past.

Part of what Seventyfive is doing is showing that East Asian designers and consumers are more than just numbers and that we are people with histories, traditions, and tastes that matter.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

All images courtesy of Seventyfive unless otherwise stated