Tianzhuo Chen is a hard man to define.

Primarily a visual artist, over the past few years he’s been producing some of China’s most attention-grabbing performance and video works, experimenting in an array of media, and has moved well beyond the confines of the art world.

Emblematic of the new wave of young Chinese artists, he’s also made his presence felt in fashion and clubbing, building a reputation for bold, bizarre, almost Bacchanalian parties via his Asian Dope Boys collective, with stints everywhere from legendary Berlin club Berghain to Paris’ Palais de Tokyo.

“I’m someone that gets easily bored with my own creations,” the prolific creator, tells us. “If I keep doing the same thing, I’ll get extremely bored. So I need to constantly shift my identity to adjust my creative process.”

We meet Chen in a coffee shop within Beijing’s 798 Art District, just as his performative exhibition piece Trance is underway at the capital’s M WOODS space. Opening at the end of October 2019, the three-day, 12-hour performance combined a dizzying array of influences.

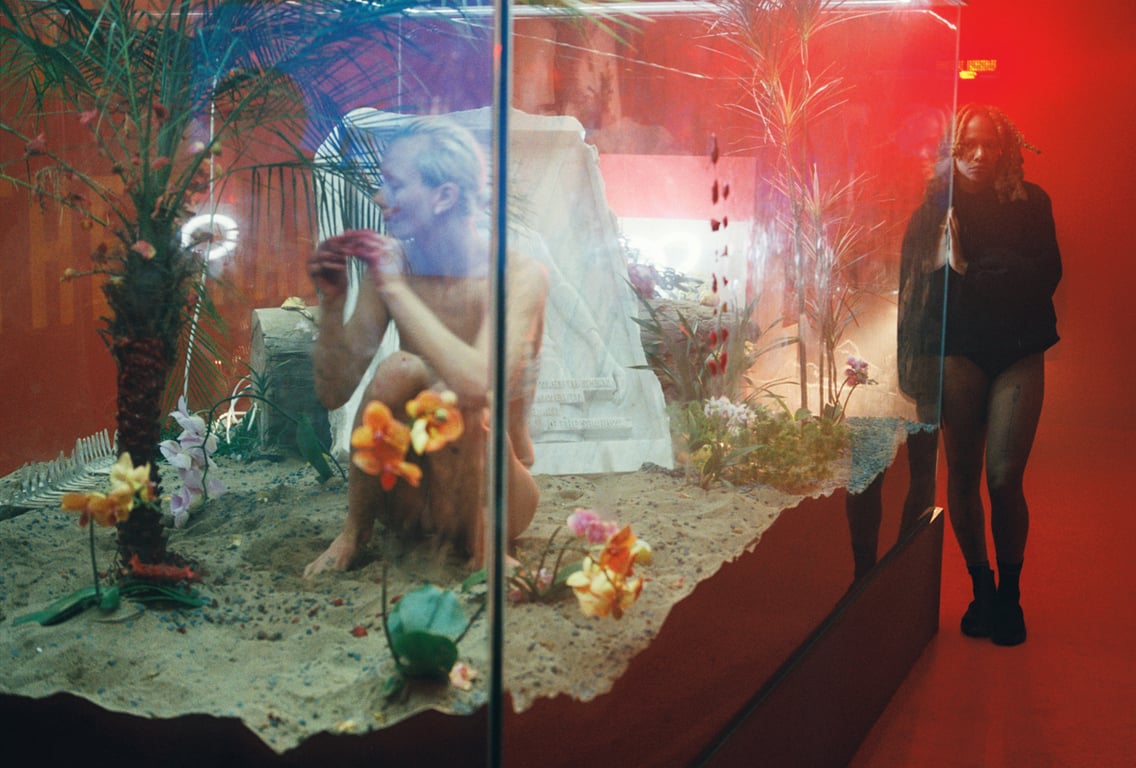

That show comprised of wild scenes of performers painted in different colors acting on an altar-like terrace in a smoggy square space. They splashed water from skinny vases onto their half-naked bodies, curling up together behind a huge screen that was simultaneously live-broadcasting their movements, while others crawled beside a skeleton lying to the side of the platform.

The intense, captivating performance was composed of six stories relating to human illusions, drawing inspiration from a variety of multicultural sources. It’s a work that excellently captures Chen’s recent creative tendencies, as it combines his preoccupation with performance and improvisation, as well as a plethora of cultural influences such as Kusozu, an ancient Japanese painting style, references to the life after death of Tibetan lama Delog Dawa Drolma, as well as the diaries of French playwright Antonin Artaud, and the spiritual letters of British poet William Blake.

The grab-bag of influences is partly informed by Chen’s own background. Born in Beijing, he received his Masters in Fine Arts from the Chelsea College of Art and Design in London after graduating from Central St. Martins with a Bachelor’s degree in graphic design.

This idea of innate multiculturalism brought about by living outside of China is something that he refutes, however. “I only stand on my own viewpoint, that is, maybe I will be attracted to a certain cultural phenomenon or attracted to something at a certain period of time,” he says.

That tendency falls in line with his aforementioned impulse to constantly shift medium in search of a fresh approach. He is an artist that is always hunting for fresh influences. His art oeuvre includes pieces that range from paper to installation, video to photography. Over the past half decade, however, he has been mostly focused on performance in various guises.

“When I was creating installations, I became interested in cinema; when I was creating video works, I thought the work might be better as a performance,” he says. “You can perfect a video work through intensive editing but performance is always one-off and every performance is different from another. Also, I find the direct emotional exchange, the direct relationship between performers and the audience, to be very interesting.”

This is a relationship that Chen has also explored in the club space through his nightlife collective Asian Dope Boys, as well as through his performative art exhibitions, which tend to be open and allow for audience participation. His Acid Club performance at Star Gallery in Beijing in 2013, PARADI$E BITCH at Bank Gallery in Shanghai in 2014 and his eponymous solo exhibition at Palais de Tokyo in 2015 all involved pulling the audience into the art to some extent, with Chen as master of ceremonies.

Related:

Club Seen: Asian Dope BoysChen Tianzhuo’s nomadic club night has shifted its spotlight to local artists and musicians over the last yearArticle Aug 15, 2019

Club Seen: Asian Dope BoysChen Tianzhuo’s nomadic club night has shifted its spotlight to local artists and musicians over the last yearArticle Aug 15, 2019

For someone whose Instagram features myriad out-there images and who is in the midst of attempting to induce a trance-like state out of gallery goers, Chen is a surprisingly laidback interview subject when we meet. He can be, as he tells us, a very serious person and he regularly offers considered ruminations on his own work.

“I create ephemeral temples in different places in order to question the fragility of our contemporary lives and dwindling morality and beliefs,” he once told The Daily Beast.

To achieve this, Chen regularly borrows from a broad sweep of iconography, aiming to create works that reflect the individuality of his generation and the flood of fragmented information and experiences that comprise their lives. The marijuana leaf, the Eye of Providence, skeletons, neon lights, kawaii (cutesy Japanese) imagery, BDSM and South Park’s Cartman, as well as hip hop, pop and experimental electronic music all make regular appearances. If this sounds like flippant hipsterism, Chen argues that these archetypal images are framed in such a way as to reveal deeper meanings, ancient ideas that seem to have been demoted to irrelevance in everyday life.

“Actually the reason why I started Trance is that I think life nowadays lacks narratives of fairytales and mythologies,” he says. “People see this information on the internet, or see news about some technological changes: we can become super humans, we can edit genes, we can correct our defects, we can edit embryos and create a better type of human being. But our control of our own spirit is unprecedentedly out of control, while our mastery of the physical body is unprecedentedly in control.”

Chen’s work therefore suggests an interest in filling this void, creating a type of contemporary religion by building on primitive beliefs, pop culture and everyday objects, morphing average people into “gods” as they each partake in his peculiar trance, reaching “a state of madness” after “enlightenment.”

“There is no such trend of mythology in daily life now, there are no collective rituals,” he says. “Every one of us is in our own bubbles and our online information intake looks to be equal, but in fact we only absorb information based on our biases or those imposed by others. So I hope to create this kind of trance, a kind of religious ceremony that exists because it has no time limit.

“In today’s society, there’s a kind of truth to that.”

This is perhaps the most interesting aspect of Chen’s work, his preoccupation with the past. By using religious symbolism, he goes against the grain of contemporary Chinese art that is often obsessed with the future. While art, film and even musical trends have consistently pointed towards concepts of post-humanism, of digital bodies or android-like characters set in the future, Chen’s ideas revolve around historical archetypes of mankind, symbols that have been, ironically, forgotten in this age of information.

By transcending multiplying media and cultures, Chen also overcomes dullness and cultivates his creativity. It’s fitting then, that a common slogan on his work is “Ordo ab Chao” — “order out of chaos.”