On Thanksgiving Day 2020, Xavier Murphy and his family went online for a Zoom reunion decades in the making. In South China, thousands of miles away, 93-year-old Hermede Shim Kong, Murphy’s uncle, was on the other end of the video call.

Murphy, who was born in Kingston, Jamaica and now resides in South Florida, was in his 20s when he first heard rumblings of a mysterious relative back in the ’90s.

“I thought it was almost like a myth,” he recalls. “I remember one of my older aunts saying we have an uncle — we can’t find him, but he’s in China — and that’s the first time I remember hearing about it.”

From there, Murphy pieced together bits and pieces of his fabled uncle’s backstory at family gatherings. Details were scarce, but the uncle was said to be the child of Murphy’s maternal grandmother, born before she married his grandfather and gave birth to her other children.

Xavier Murphy in Florida

“As I grew older, as we started having more reunions, as I started to question my aunts about things, then it was like, ‘ok, there’s definitely something here. Let me see what I can pursue,’” Murphy tells RADII.

Unsurprisingly, tracking down his uncle with little more than word-of-mouth recollection was no easy task.

He learned his uncle’s name and that his uncle’s father, Philip Shim Kong, owned a shop in downtown Kingston. He took the clues to the Chinese Benevolent Association of Jamaica, but hit a dead end. His uncle remained an enigma.

Out of Many, One People

The International Organization for Migration estimates 60 million people make up the Chinese diaspora today — a combination of emigrants and their descendants defined as ethnic Chinese residing outside of the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

Originally home to the Taíno indigenous peoples, the colonization of Jamaica began with the Spanish in the 16th century. The British took control of the island in the 17th century, and waves of migration followed — first with the import of enslaved Africans, then through indentured labor that brought people from Europe, and later India and China to work on sugar plantations.

Through this cultural milieu, Jamaica’s national motto, “Out of Many, One People,” was born.

The Jamaica Coat of Arms. Image via Wikimedia

The first wave of Chinese migration began in 1854 when 472 Chinese people came to the island from Panama. A subsequent wave of Chinese laborers came from British Guiana and Trinidad between 1864 and 1870. An additional 680 workers, predominantly men of the Hakka ethnic group, arrived directly from China in 1884.

Around the turn of the century, anti-Chinese sentiment led the government to issue stricter rules for migrants from China — not unlike Chinese exclusion policies enacted in the United States and Canada — requiring Chinese immigrants to register and provide personal information and an address to authorities.

By the mid-1930s, 6,000 Chinese people lived in Jamaica, and additional measures were added to restrict immigration, including an entry fee, language proficiency testing, and medical examinations.

More than a decade later, the number had doubled. The 1947 census lists 12,394 Chinese people in the country, including those born in China, those born on the island, and individuals of mixed Chinese-African ancestry.

Jamaica saw anti-Chinese riots in 1918, 1938, and 1965, and many Chinese Jamaicans moved elsewhere in the ’70s, mainly to Canada and the United States. Many more remained, though, setting up storefronts and businesses through the 1900s, and a wave of new arrivals from Taiwan and Hong Kong came in the ’80s. Others, like Hermede Shim Kong, returned to their ancestral homes in China.

Today, ethnic Chinese people make up around 1.2% of the Jamaican population — a small but thriving community whose cuisine and culture are part of the fabric of Jamaican society.

Notable Chinese Jamaicans include rapper Sean Paul, dancehall artist Shenseea, and the founders of pioneering independent reggae and dancehall record label VP Records, Vincent and Patricia Chin.

A Lucky Break

The hunt for Murphy’s uncle took a positive turn when he discovered My China Roots (MCR) in 2020, a Guangzhou-based company (with branches in Beijing and London) dedicated entirely to helping people trace their Chinese ancestry.

The team at My China Roots said Murphy was going about his search all wrong: Instead of looking for his uncle, they needed to find information about his uncle’s father. So, they returned to Kingston’s Chinese Benevolent Association (CBA) to approach the search from this new angle.

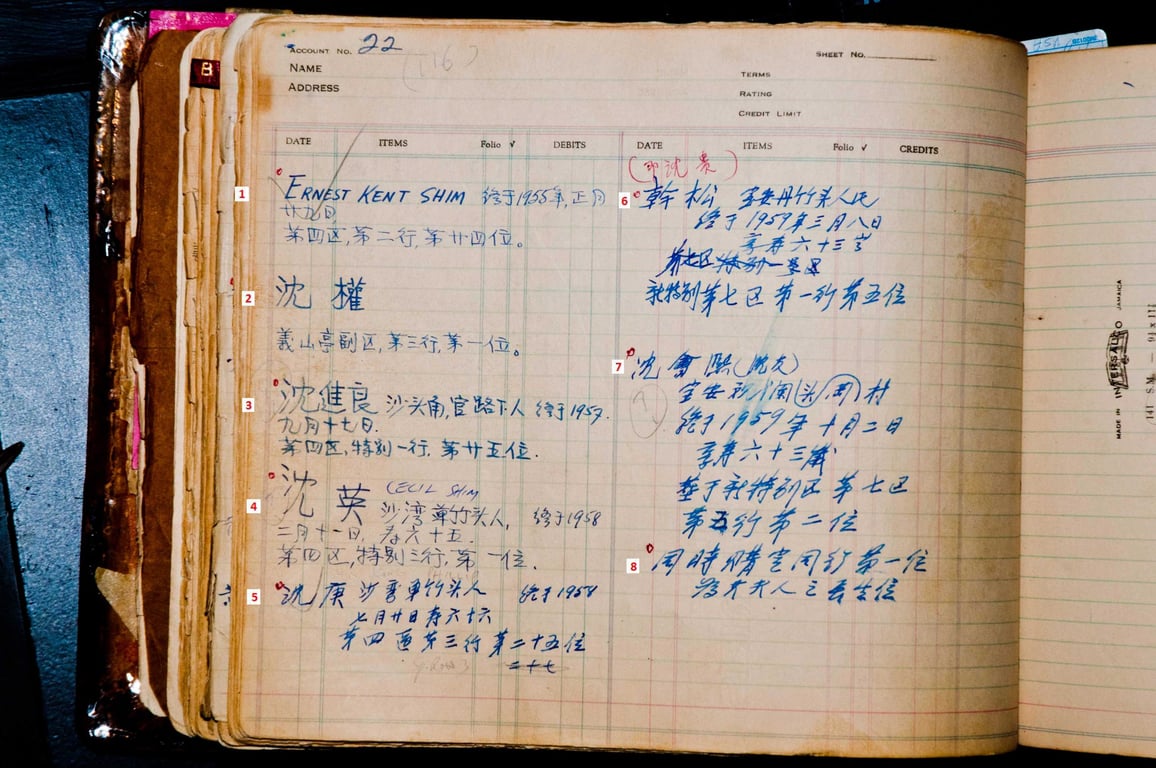

The gravestone of Philip Shim Kong lists Hermede’s birth name and the name of his brother

The CBA is the caretaker of a Chinese cemetery in Kingston. Over the past decade-plus, they’ve undertaken the painstaking effort of cleaning up the cemetery and photographing, translating, and digitizing information from the graves — including names in Chinese and English and the villages people came from.

The gravesite of Murphy’s uncle’s father, Philip, was among those in the Chinese cemetery in Kingston.

Through the CBA, My China Roots found the Chinese names of Hermede and Philip, and the elder relative’s village in China. From there, the search took off.

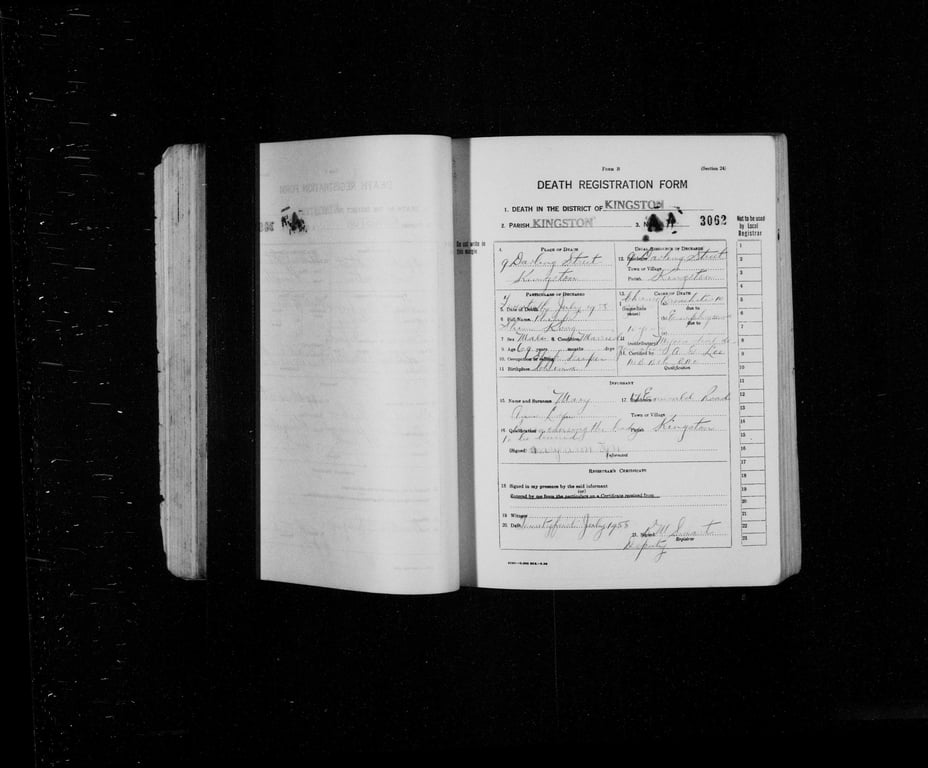

Philip Shim Kong’s death certificate, found in the Jamaican Civil Records on Familysearch.org

My China Roots sent researchers to the village in Shenzhen where the uncle’s father came from. They also connected with a blogger named Mr. Lin who introduced them to Hermede’s daughter, Shen Anli.

In a matter of weeks, they made contact with Murphy’s uncle — still alive and well, with a family of his own.

My China Roots learned Hermede has two daughters and is the eldest of three brothers, all children of Philip. Hermede’s Chinese name is Shen Yingqian (沈英强), but interestingly, his birth name (which is on his father’s tombstone) is actually Guanfa. (For clarity’s sake, we’ll continue referring to Murphy’s uncle as Hermede for the remainder of this article.)

Philip Shim Kong’s burial log reads: “Shem Kong: a native of Danzhutou, died July 20, 1958, at age 66. Buried section 4, row 3, grave no. 25”

My China Roots’ success tracking down Hermede came as a massive surprise to Murphy.

“I was shocked. When I reached out, I was saying I’d love to find relatives because I do not think he’s alive — I thought he would have passed,” says Murphy. “I was elated. I get goosebumps just thinking about it, finding him alive.”

From the Caribbean to East Asia

Hermede Shim Kong was born in 1926 to a Chinese father from Shenzhen and a Jamaican mother, Ruth Deeble-Reid, in Kingston, where he lived until age 3 before returning to China with his father.

Unfortunately, when Hermede arrived in China, his Jamaican birth certificate was taken by Hong Kong immigration officials. Interestingly, his daughter told researchers her father’s Hong Kong-born younger brother was also given the name Guanfa in the hopes of reclaiming his brother’s birth certificate from Hong Kong authorities. (A ploy that seemingly didn’t pan out.)

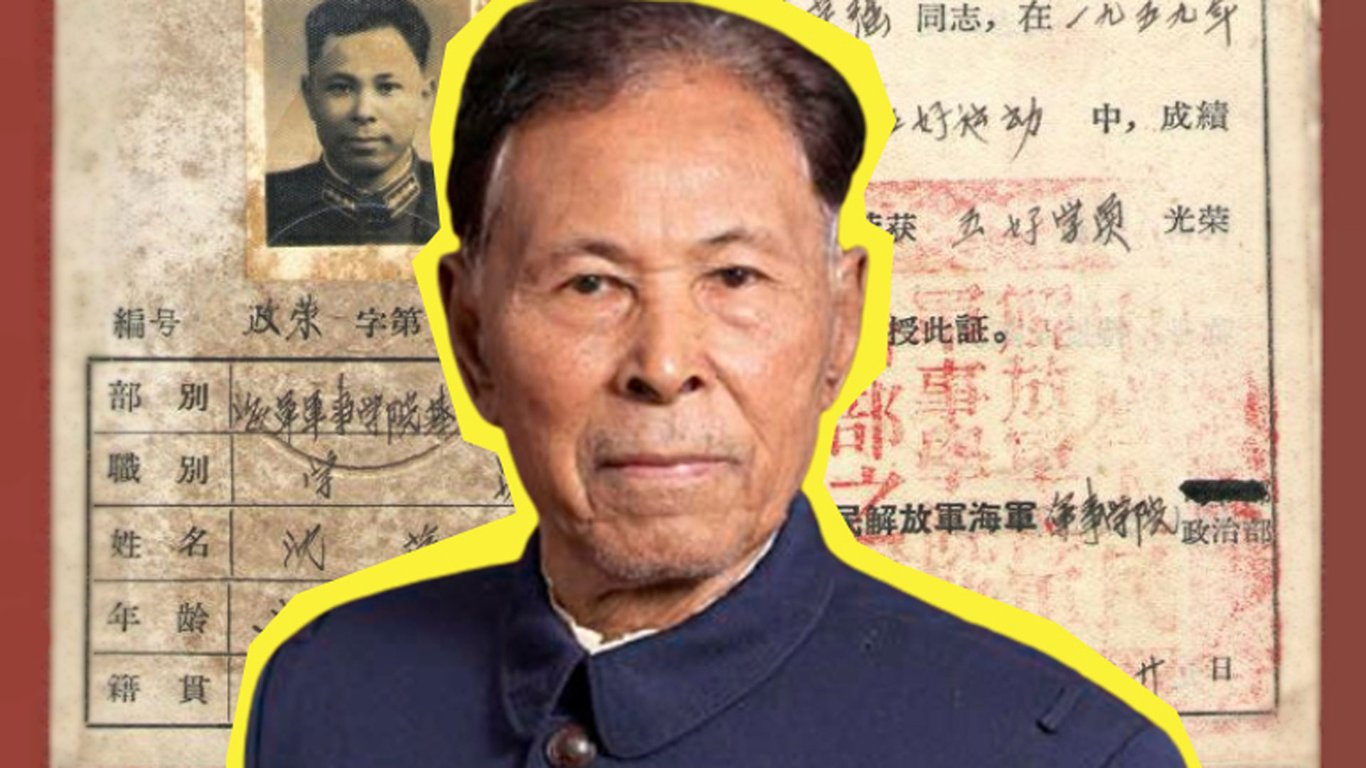

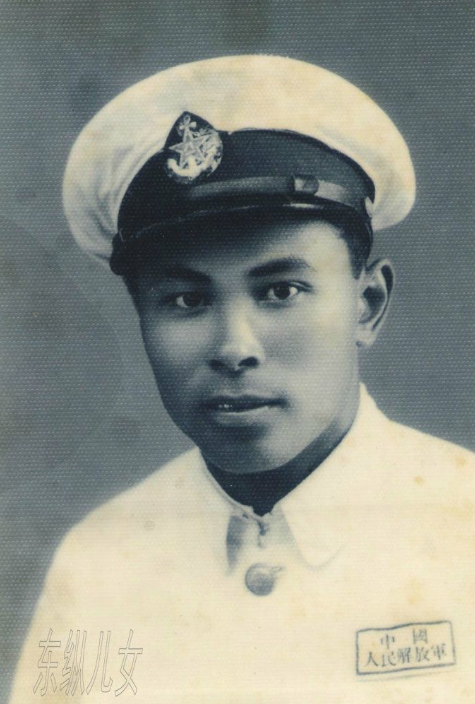

A young Hermede Shim Kong in military garb

His dad eventually returned to Jamaica, leaving Hermede to be raised by his adoptive mother in Shenzhen’s Shuikuxin Village. He spent his childhood farming and raising cattle with other kids in the neighborhood.

Now 95 years old, Hermede has lived nothing short of an extraordinary life.

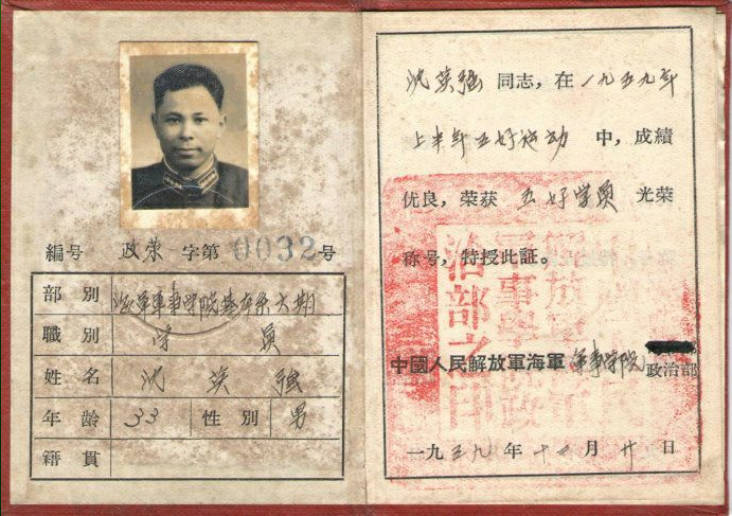

Hermede Shim Kong’s naval academy booklet

In fact, part of what made finding him easier than expected is that he is something of a celebrity in his community: During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), Hermede fought with guerilla forces against Japanese occupiers in South China. Through his courage and skill in battle, he moved up the ranks to the position of naval lieutenant.

Today, he is honored as a war hero, and My China Roots found several articles about Hermede’s military service in Chinese publications, including this one from SZNews. He’s described as a Danzhutou native of mixed race, born in Jamaica in December 1926.

Hermede retired in 1985, but he continued giving back to the community through volunteer work as a teacher and mailman.

Hermede Shim Kong is a decorated soldier who fought against Japanese occupiers

While he hasn’t returned to his country of birth, Hermede never forgot about his family back home. On the contrary, he was looking for them, too.

Over the years, he reached out to overseas Chinese associations and even tried to get his birth certificate back, all without success.

Incredibly, Hermede almost connected with his Jamaican family years earlier: He sent a letter to a man from a Chinese association in Kingston in hopes of reaching his relatives, but it was ultimately returned to China, where it remains in his possession.

Murphy’s wife Karen is also of Jamaican-Chinese ancestry, and coincidentally, the letter was addressed to a Mr. San Lyn Shim, who happens to be her close family friend. Even more shocking, the address on the letter was the same street, Evelyn Crescent, where Murphy grew up — just six houses away.

The Reunion

The first family reunion was a magical affair. Across the Pacific Ocean, Hermede sat with his children: Dressed in a blue suit and striped tie, he held the letter he mailed out years earlier, with the Chinese and Jamaican flags displayed proudly behind him.

Hermede Shim Kong with his family and a translator during the first reunion

“For years I heard about you. I heard that my grandmother had a first child, and I tried to find you,” Murphy said to his uncle through a translator provided by My China Roots. “We are so happy to find you and we hope one day that we can come and visit, and meet you.”

“For years I heard about you. I heard that my grandmother had a first child, and I tried to find you,” Murphy said to his uncle through a translator provided by My China Roots. “We are so happy to find you and we hope one day that we can come and visit, and meet you.”

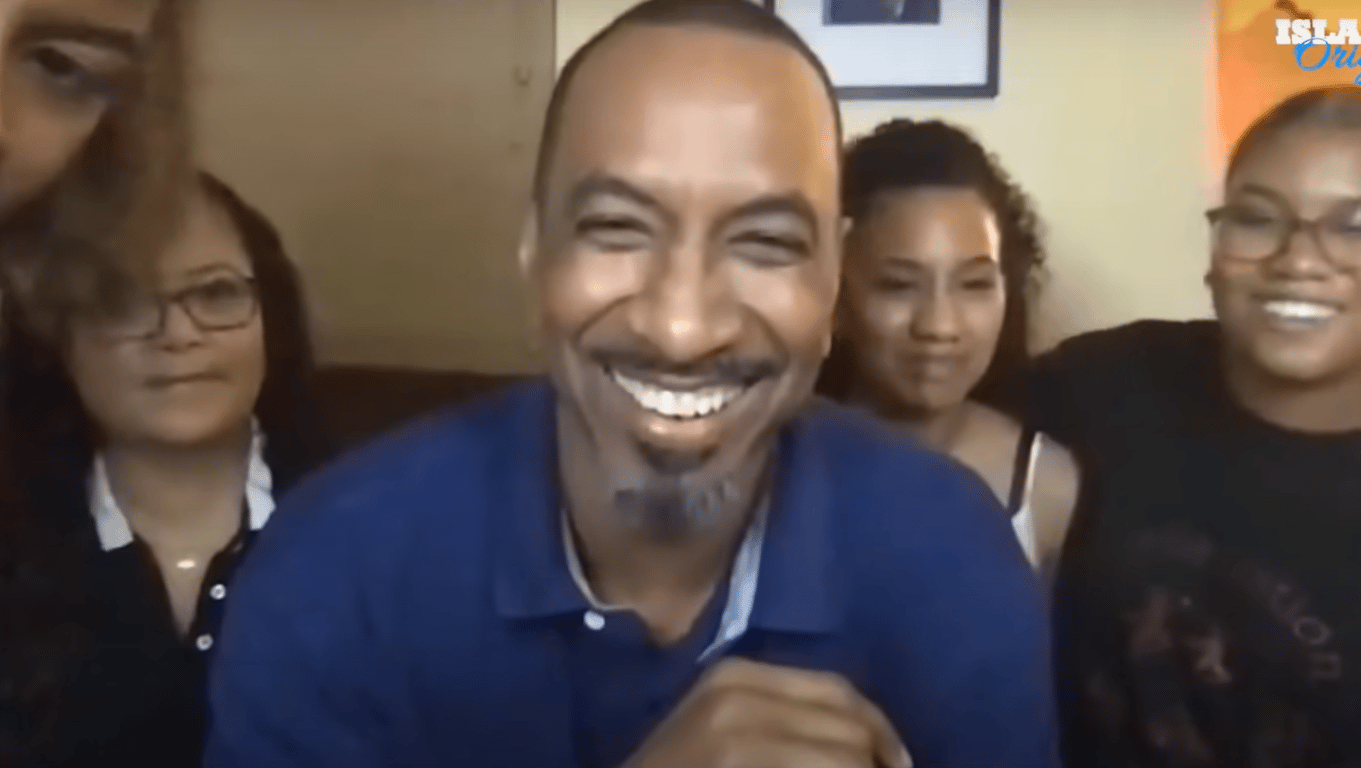

Murphy estimates that there were 30 family members on that first Zoom call, including his uncle’s children and seven Jamaican siblings.

Murphy and his family on Zoom for the first reunion

“That first encounter, everyone was so excited — we were talking over each other,” says Murphy. “What he was particularly excited about was seeing his sisters … that was good. You could see the excitement on his face when he realized, ‘hey, I have real sisters,’” he adds.

Speaking through the translator, Hermede expressed the same sentiment: “I am very happy to finally meet my sisters. I knew I had a brother, but did not know I also had sisters, and my daughters are happy they have finally found their aunts,” he said.

Murphy says his uncle remarkably resembles his second-oldest aunt, and the group was touched to see their likeness.

Hermede Shim Kong and his daughter

Unfortunately, due to the language barrier and the challenge of arranging a translator, they’ve yet to do another group video call with the family. But Murphy keeps in touch with his cousins and shares photos through WeChat.

And the family in Jamaica hopes to visit their relatives in Shenzhen when it is possible to do so.

Murphy on the Great Wall in Beijing

“It’s at the top of my list. It’s one of the first trips I want to make,” says Murphy, who visited Beijing and Shanghai with his wife several years ago to explore her Chinese heritage.

A Labor of Love

When potential clients reach out to My China Roots, they are sometimes turned down for lack of sufficient information. Initially, that seemed to be the case for Murphy, too, who only provided them with his uncle’s English name.

“Without a Chinese name, it’s incredibly challenging, borderline impossible, to get anywhere,” says Clotilde Yap, who led the search for Murphy’s uncle and has been with the company since 2017.

In his initial inquiry, Murphy said his uncle’s father came from Hong Kong, but since South China port cities were the point of departure for most people leaving the country at the time, Yap says this bit of information was initially discouraging as well.

“When we take on [a client], we expect in 70% of the cases that we will find something. But for this particular case, it would have been really difficult to say,” Yap tells RADII.

Clotilde Yap has worked with My China Roots since 2017

Fortunately, things went remarkably well. They began the investigation in November 2020, and the family was communicating over Zoom before the month’s end.

The majority of My China Roots’ clientele come from the US, Canada, Australia, the Caribbean, Singapore, and Malaysia.

The company works on a success-fee basis, meaning they charge a fee upfront to cover research, and the rest of the cost — typically in the 2,000 to 2,500 USD range — comes after they find the desired info.

Investigations typically take at least one month, but Yap says some clients have worked with them for years — digging further and further into their familial roots after the initial findings.

But as time passes and China develops, the work they do grows more difficult: Villages like the one where Hermede grew up are torn down to satisfy the inertia of urban expansion, and community members are relocated.

“We always try to tell people that, although we don’t know what we will find out, now is the time to do it and not in 10 years’ time, when there really will be nothing left,” says Yap.

Before working with My China Roots, Yap traveled from the UK to China to track down her own relatives in a Fujian village that shares her surname.

“I had always struggled with knowing where I fit in, and when I was there, they were like ‘no, no, you’re Chinese, you’re part of this family.’ There was no question about it, there was no doubt,” she says, adding that it was “one of the most empowering, spiritual experiences I’ve ever had.”

But beyond her journey of self-discovery, Murphy’s story was one of her most memorable.

“Xavier’s story is one of my all-time favorites … I remember at the beginning being really touched by his energy and his desire to track down this uncle,” says Yap. “I think very fondly of that reunion. That’s exactly why we do the work we do.”

Xavier Murphy’s Law

Murphy’s main advice for others in search of Chinese relatives: “Every detail matters. That’s the one thing I would tell anyone if you’re doing this. Any interactions you’ve had with the person — every detail matters.”

He’s pleased about his Chinese family’s willingness to connect — something that isn’t always the case for clients of My China Roots, and he’s warmed by the knowledge that uncle Hermede was just as curious as he was.

“I was searching for him, he was searching for us, and that was good to know. When he put that envelope up, it was just like, he’d been searching — we knew,” says Murphy.

Murphy and his wife Karen on their first trip to China

It may be a while before Murphy and his family can visit China, but they’ve got another surprise in store for their relatives across the pond: “Our goal is to try and have one relative from China come to the next reunion,” he says.

“We know our uncle probably can’t because he’s gonna be 96 this year … but to have one of the cousins come and visit — we talked about it as a family, and that’s our goal.”

This improbable journey — with more than a decade elapsed since he became serious about the search — offers Murphy a renewed sense of kinship to the world beyond his home.

“There’s this totally new connection that’s there, that’s one part of how it changed my life,” he says.

“It’s brought a new awareness for me of China and just how connected we are.”

Xavier Murphy is the founder of Jamaicans.com and is an active member of the South Florida community. He has worked as a leader in various organizations, including as president of the Association of Internet Professionals, South Florida branch, and is the founder and president of the Jamaica College Old Boys Association of Florida.

Check out the video below, courtesy of Island Origins and Jamaicans.com, to learn more about the reunion and the work that goes into tracing one’s Chinese heritage.

Editor’s note: RADII founder Brian Wong is an investor in My China Roots. That said, RADII’s editorial staff operates independently, and this story was selected and run based on its own merits.

All images courtesy of Xavier Murphy and My China Roots