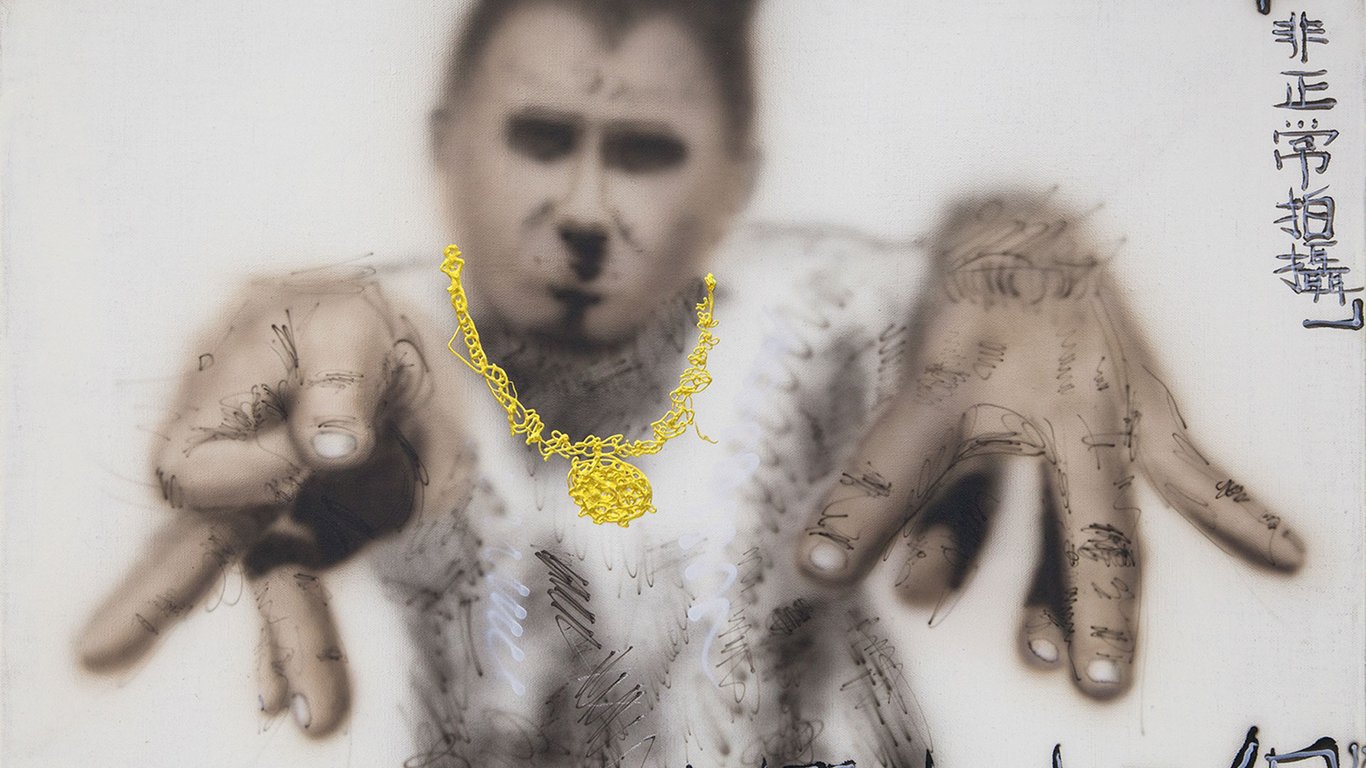

Mike Tyson soaking in an inflatable pool with his Bengal tigers, Sailor Moon in latex fetish wear, wrestlers grappling each other in golden chains and Calvin Klein briefs — welcome to the world of ¥ouada, a Hangzhou-based artist mixing elements of street culture with a profusion of anime and pop-culture references.

He renders everything in bright fluorescent colors, and his various canvases and sculptures can be found in museums, galleries, and the living rooms of art collectors all around the world.

Ludicrous and sometimes downright outrageous, his work is a mismatch of characters, symbols, and incidents that come across as an extreme visual satire of society. Still, ¥ouada takes no prisoners. He does not intend to make bold statements or raise moral judgments, but to ridicule everything he sees.

“I don’t care too much about political and social issues or if something is right or wrong,” he says. “All I want is to look at things from a permissive and mocking perspective.”

In any case, humor is his weapon, and his art holds up a mirror to the influences of consumerism and mass media on our lives.

¥ouada was born in 1987 and grew up in a small town in Fujian, a coastal province in Southeast China.

For as long as he can remember, his friends and family always called him ‘Ada’ (阿达), meaning ‘fool’ in the Minnan language of southern Fujian. They gave him this nickname because of his irreverent and silly personality, which he later incorporated into his artistic identity and, along with the yuan sign, ¥, his professional title.

¥ouada grew up in the 1990s and witnessed an explosion of international pop culture entering China through mass media, mainly television. Like most Chinese kids of his generation, he was into Japanese anime. Television also exposed him to more subversive worlds, many of which appear in his art today.

“I’m really into street, gangster, and even prison culture — probably because of the movies and TV shows I enjoyed as a child,” ¥ouada says. And as the internet developed in China and around the world, it exposed him to a whole new realm of references.

“Chinese kids born in the 1980s often looked for ‘cool’ things online when they were growing up,” he explains.

The 1990s were a time of intense development, social transformation, and urbanization in China. There was a shift from a collective spirit towards a more individualistic, materialistic, and even defiant zeitgeist.

It was then that graffiti appeared in big cities, which, like elsewhere, didn’t please city officials. ¥ouada was part of the emerging subculture.

He began to cover walls with graffiti as a teen, and his art was unique from the start, reflecting his particular terrain and culture. While relatively small, his hometown had its share of local gangsters and “temple mobs.”

“China has its own unique graffiti culture, small-town youth culture, and urban subcultural groups,” he says. “The atmosphere in Hangzhou, for instance, is generally quite fun.”

It was in Hangzhou that, in 2011, he graduated from the China Academy of Fine Arts with a focus on painting. He sees the city as a thriving space for creativity thanks to the influence of institutions and independent initiatives that pop up from time to time. He explicitly mentions LBX Gallery, now-closed, and the art group Martin Goya Business as safe spaces for artists to meet and for subcultures to flourish.

All this provided the breeding ground for ¥ouada’s art. Today, his inspiration is “fragmented,” as he puts it, also arising from the small things he observes in his daily life — often the most mundane objects.

For instance, we can see references to FamilyMart, the Japanese convenience stores all too common in China, and the products they sell. Nongfu Spring bottled water and Asahi beer cans are recurrent themes in his work, sometimes incorporated fully into his sculptures.

¥ouada also mines references from his hearty internet diet and infinite scrolling through social media — a numbing habit, he knows, but one reflective of the modern world.

He is drawn to the seemingly effortless way platforms like Instagram and TikTok sort and recommend visual material based on his preferences — particularly their immediacy and the diversity they exhibit — bringing a certain closeness and proximity to stories from around the world.

But nothing amuses and shocks like ¥ouada’s characters, the heroes he recycles from the TV shows he watched as a kid. The way he depicts them, however, is anything but heroic.

“Classical artists draw noble themes and mythical characters. I draw anime characters, but I’ll incorporate them into a gangster lifestyle, parties, or some sort of subculture. I’ll even draw them in a slutty, nasty, and vulgar way, full of immorality,” he says.

His characters are often holding guns, drinking, or equipped with some drug-taking apparatus. Celebrities and politicians also make cameos on ¥ouada’s canvases.

¥ouada himself looks like he could have stepped out of one of his paintings. In his social media posts or videos, we occasionally see him in thug style, mesh cap, logo tee, and high-top sneakers.

But, he admits, his reality has changed from his street days.

“Currently, since I have a young kid, I spend most of my time taking care of family life and creating art,” he says.

Some things remain the same, though. Even if ¥ouada works on canvas, he uses airbrush and spray techniques to cover his brushstrokes and add a blurred effect to his paintings. It’s something he carried over from his graffiti practice, along with the ethos of boldly blurring the lines between legal and illegal, moral and immoral, art and vandalism.

Additional reporting by Lucas Tinoco

All artwork courtesy of ¥ouada