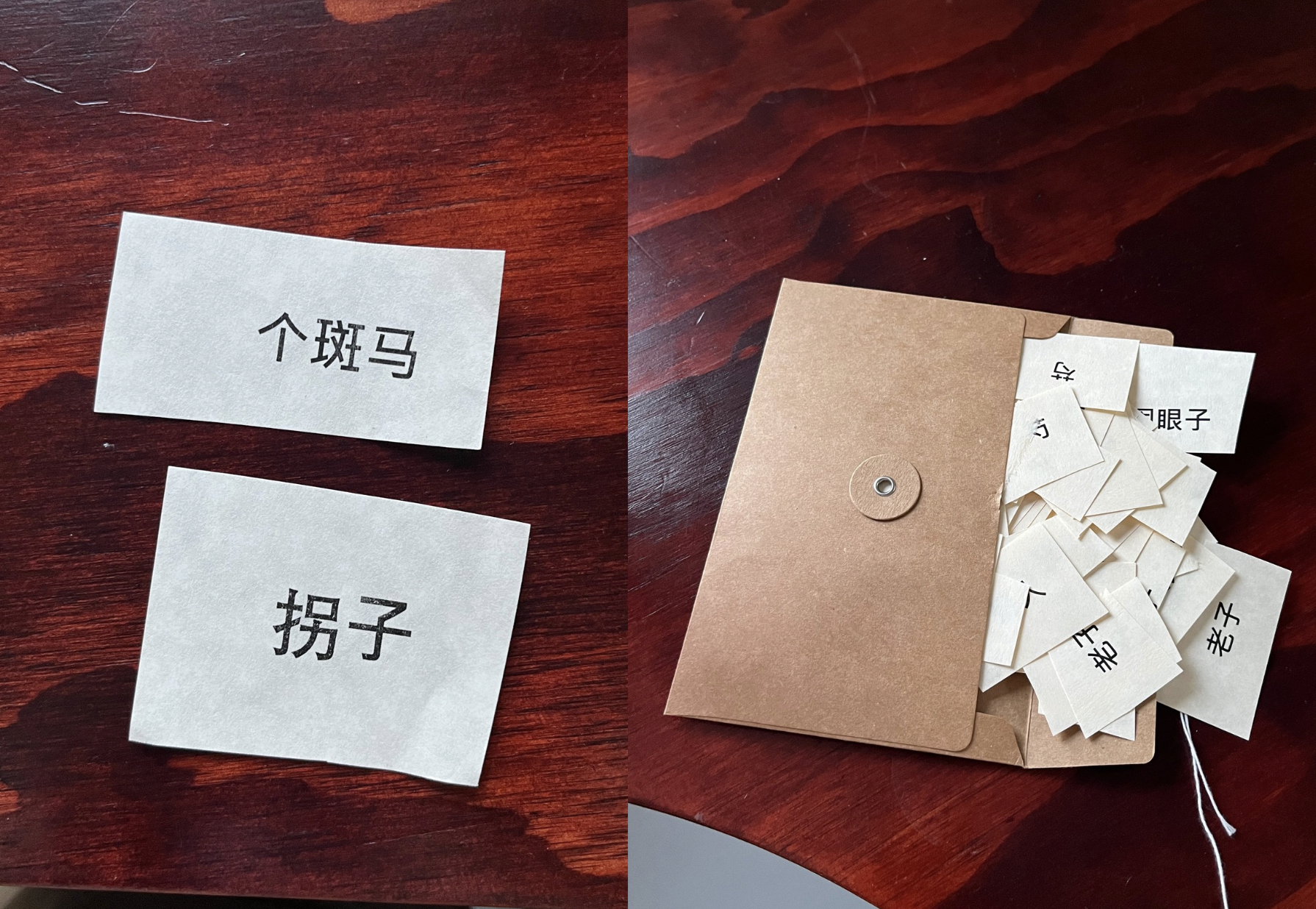

In a tightly packed exhibition space in downtown Manhattan, Chiarina Chen stood before a full audience, presenting her spoken essay in the Wuhan dialect. Before the presentation began, an envelope was passed around the room, and inside were slips of paper with Chinese phrases written on them. Mine read “个斑马” (gè bān mǎ). I knew its literal meaning—a zebra—but there has to be more to it. Later, Chen explained that these were colloquial phrases from Wuhan. Depending on the tone, “个斑马” can be an expression of frustration, surprise, or excitement.

Her presentation, titled, In the memory of my Wuhan dialect, wove together reflections of the pandemic and childhood memories of the city. It was a deeply introspective meditation on her relationship with her mother tongue and dialect of the Hubei province, Wuhanese, which followed her throughout her life. Growing up, Chen was discouraged from speaking the dialect. Speaking “proper” Mandarin meant you were civilized and educated, which was a common experience for many Chinese children. Working in NYC as an arts curator, Chen still never had the opportunity to speak Wuhanese, even being outside of China; the two worlds just don’t intersect for her.

“How come the more ‘civilized’ Mandarin and English I speak, the more I feel like a fool sometimes?” Chen asked.

The end of the spoken essay featured a crash course on Wuhanese. Chen taught us how to pronounce the phrases on the slips of paper we were holding. The room was filled with mispronunciations, giggles, and shy mumbles from an audience of diverse backgrounds. But beneath the humor was a shared appreciation for a dialect that transcended cultural boundaries.

The event was part of the “Accent Dialect Corner” series, curated by Accent Sisters, a bilingual bookstore and art space that connects Asian diasporic writers, artists, and activists. Past events have celebrated Shanghainese, Cantonese, Sichuanese, and more. Their latest program, “日落过早: Breakfast After Dusk,” explored the sounds of Hubei Province. In NYC, where countless cultures intermingle, some inevitably get lost. This night, however, the Accent Sisters handed a piece of home back to their audience.

The centerpiece for the evening was “The Aftersound,” an audio essay by writer and educator Ou Ning. Layered with narrations in multiple dialects, field recordings from across Hubei, and music interludes, the sonic experience offered a 25-minute-long escape from the bustlings of NYC. Ou Ning drew from his culinary memories of his time in Hubei. Other voices also spoke of food, alcohol, and cultural experiences that crossed borders and transcended time.

Li Juchuan read an excerpt from 觞政 (Shangzheng), a 16th-century poem by Yuan Hongdao about drinking etiquette. But the kicker is that Li delivered the poem in his Shashi dialect, creating a far more grounded and intimate experience. The narration was followed by the “Shashi Nocturne,” a song written by Japanese soldiers stationed in Shashi during World War II.

Ou’s field recordings captured the whirr of levees, chatter in village back alleys, and announcements at train stations; it’s a peek into the everyday sounds of small-town Hubei. But the essay also brushed against memories of Covid-19. It seems like when we talk about Wuhan, we can’t escape from the elephant in the room. My conversation with attendees often fell into silence when the topic of the pandemic arose. I noticed some were teary-eyed. Others brought up director Lou Ye’s latest work, An Unfinished Film, a mockumentary about Covid lockdowns. It’s a collective trauma we pretend to forget, but its effect still ripples.

In “The Aftersound,” Ou also featured “Lumo Road,” a song by the Wuhan punk band SMZB. It celebrates the nightlife on Lumo Road; the restaurants, bars, bands, and friends who showed up to drink and have fun. Written in the tail end of 2019, Lumo Road soon became a fractured memory for the city’s punks. With its working-class roots, Wuhan has a long history of resilience and rebellion. In 1911, an uprising there sparked the Xinhai Revolution, eventually ending China’s last imperial dynasty. In the 1990s, Wuhan became the birthplace of the Chinese punk scene. Three decades later, it became the epicenter of a global pandemic.

Hubei has a beloved morning ritual: 过早 (guò zǎo), which involves going out for breakfast as the first light rises. It’s quite a lively scene, with the hollering of street vendors, bike bells jingling through the crowd, and the sound of frying, boiling, and chopping. In Wuhan, breakfast isn’t a light affair; instead, it’s heavy on carbs with lots of fiery spices to wake you up. Classics include the 热干面 (rè gān miàn), or hot dry noodles, where each strand is coated in thick sesame paste and chili oil, and 豆皮 (dòu pí), where minced meats and sticky rice are wrapped in a mung bean and egg crêpe.

As dusk fell in NYC, both dishes were freshly made and served to the attendees. We were twelve hours behind Wuhan’s guozao, but artists John Tsung, Li Jiaoyang, Xue Tang, and Yuan Zichen were determined to transport us there. Every pot, pan, knife, and cutting board in the makeshift kitchen was mic’d, delivering an authentic soundscape of a Wuhan breakfast shop. Close your eyes, you hear grandma busy in the kitchen. Open them, and you see neighbors from all over the world having guozao together.

The exhibition also featured a crash course in the lesser-known Zhongxiang dialect by musician Siyi Chen. She also delivered a guzheng-jazz reinterpretation of a poem by Yu Xiuhua. Artists Zijie and Gong Hao screened their black-and-white silent film Silenced Fantasia, where the fictional city of Fantasia is struck by a deadly virus and placed under quarantine. Eventually, young rebels led the city back to normality. The film ended with a footnote: “Any interpretation of such characters and events is purely subjective.”

I spent the pandemic in NYC and remember a popular Wuhan restaurant being vandalized and shut down. I also remember Wuhan friends who faced racist and distasteful comments. In her essay, Chiarina Chen noted, “Before the pandemic, most of my friends who hadn’t been to China didn’t know where Wuhan was. I loved talking about it… After 2020, no one didn’t knew Wuhan. No one ever asked where it was again.” My friends from Wuhan tell me it’s a common experience; they rarely talk about the city now. Everyone already “knows.”

As Silenced Fantasia played in the background, guests lined up for food. The clatter of cookware, the hum of conversation, and the smell of spicy noodles filled the air, drawing attention away from the film. Just as images of a quarantined city are overshadowed by the warmth of Wuhan breakfast, it seems Wuhan—and the rest of the world—is slowly finding its way toward healing.

Cover image via Accent Sisters.