A five-point red star cuts the sky with rays of hope. Underneath it, a young and muscular Chinese man, wearing nothing but his olive-coloured army hat, holds his left leg against his chest, covering his penis. He puts his index finger to his lips in a gesture of secrecy and enticingly gazes at the viewer.

In ink, watercolour, acrylic, and oil, Berlin-based Chinese musician and artist Musk Ming portrays semi-nude, athletic men alongside emblems of traditional China.

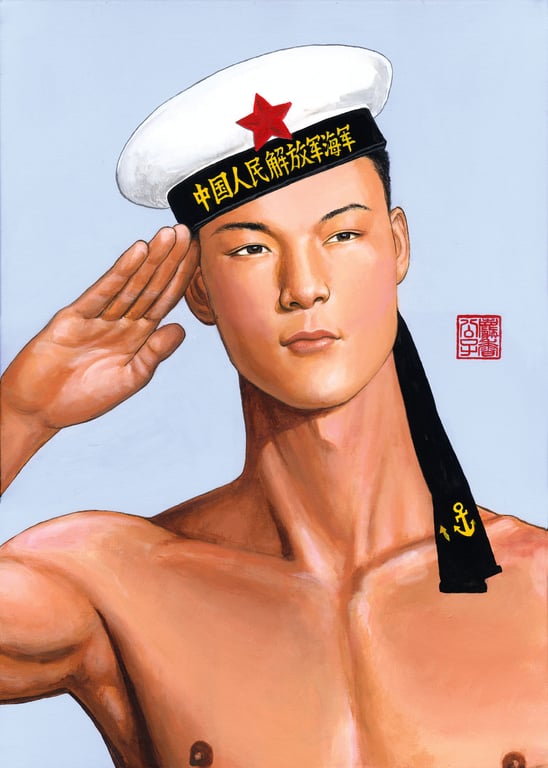

“The Sailor” by Musk Ming

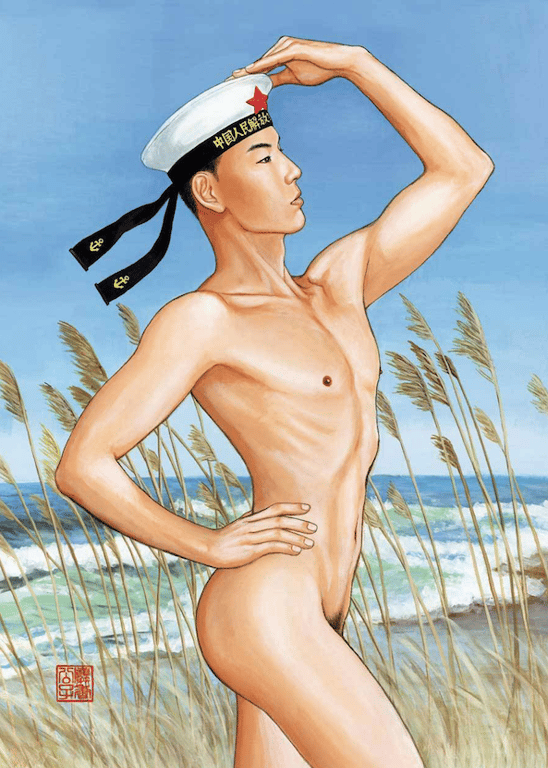

His characters are usually slim men, with little to no body hair, and a slight muscular build. Sometimes they are alone; sometimes, accompanied by other men. They never reveal their genitals, but the suggestion is always there.

Ming’s experience growing up in a strict militaristic environment laid the groundwork for his homoerotic style. “Sensuality was a taboo. We had to hide our natural feelings and desires,” he says. “But I always thought that our body is the most natural and beautiful thing about us.”

Sensuality was a taboo. We had to hide our natural feelings and desires

”Sea Breeze“ by Musk Ming

Because of his father, Ming spent his childhood in an army compound on the outskirts of Tianjin, a city close to Beijing in northern China. He was an introverted child, drawing alone in his spare time. As a teenager, he studied Chinese ink painting and calligraphy, as well as classical painting. His subject matter, however, remained a secret until he moved to Berlin in 2005.

Ming occasionally portrays non-Asian men and women, but it’s the figure of a healthy and athletic looking Asian man that speaks to him the most. “My first image of the ideal male beauty was the young and innocent soldiers I used to see at the military residence,” he says.

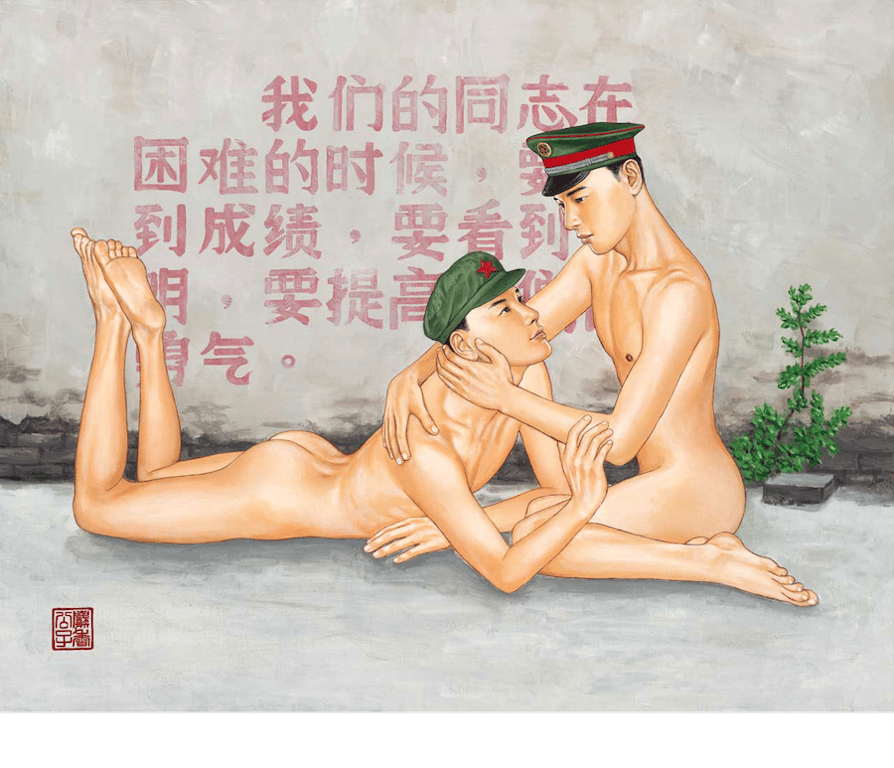

“Expectation” by Musk Ming

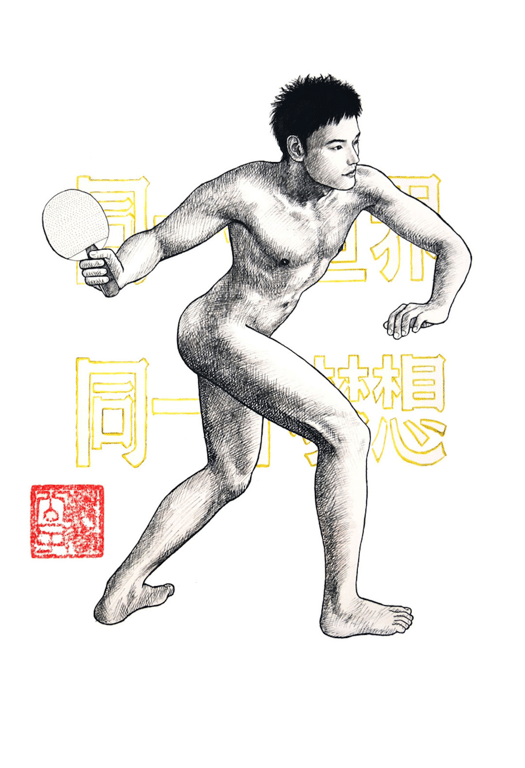

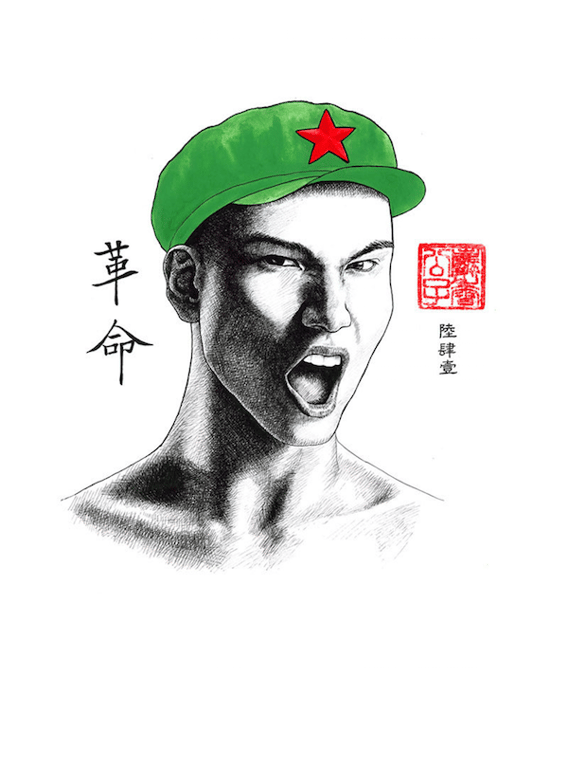

Ming borrows the aesthetics of Chinese propaganda posters by incorporating elements that were common in designs beginning in the 1950s. He uses the sunshine stripe effect in some of his pieces, but instead of statesmen and heroic figures, they encompass kissing and intimate men. As a background, we often see Chinese natural landscapes, but also an occasional sign of military power. But what stands out most are the accessories his characters wear, marked by an array of military hats.

Sometimes Ming uses slogans containing ambiguous words such as “comrade” (同志), that, besides its political meaning in China, is also used to refer to people in the LGBTQ+ community.

Another example is when, as a background for depictions of Chinese athletes, he uses the 2008 Olympic slogan “One World, One Dream” (同一个世界 同一个梦想), which expresses the notion of equality.

“Table Tennis” by Musk Ming

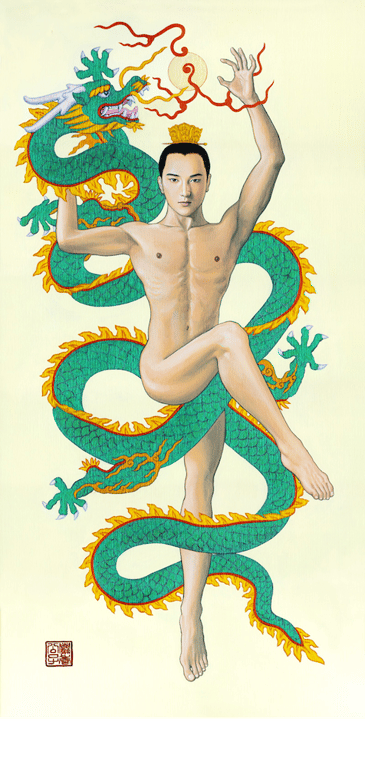

One other constant characteristic of his work is the use of traditional Chinese elements, such as dragons, opera characters, ornamented vases, and ancient architecture. He also uses a red name seal instead of signing his paintings and titles them with vertical calligraphy.

Ming’s Tumblr account is like a scrapbook for his references, it gives us a glimpse of what goes on in his mind. We find references to movies, music clips and the erotic pictures of gay magazines from the 1980s and ’90s, most of them replete with queer intensity. In the bundle, we can also see black and white photographs portraying traditional costumes and life in China at the turn of the century.

“I think my life is a juxtaposition of different elements. I spent my first 25 years in China and it was a very colorful time with the economic reform, the opening-up, and the arrival of Western pop culture, literature, and art,” Ming says.

Films that were made at the time by state-owned studios are particularly attractive to him because they represent what was thought of, at the time, as being the ideal of Chinese masculinity — military or athletic men striving for a common goal for their nation.

“Revolution” by Musk Ming

As a tribute, he produced music videos for his own songs assembling scenes from several of these movies. The result is a sensuous time warp to the China of 30 years ago. “I consider the 1980s and 1990s to be the sexiest time in China and I try to recall the ‘zeitgeist’ with my music,” Ming says.

It was in Berlin that Ming’s artistic career took off. For the first time, he was able to show his work in a gallery. He eventually opened his own art space and for four years promoted works that represented minorities and subcultures.

I consider the 1980s and 1990s to be the sexiest time in China and I try to recall the ‘zeitgeist’ with my music

“Berlin is a city of tolerance and freedom, where I can openly create and show my artwork and other’s without restrictions,” he says. But, with his work, he inevitably goes back to his origins and his experiences in China. “I’m interested in seeing people without their social disguise, in other words, the ancient soul and the naked core of China.”

“Dragon Dance” by Musk Ming

Ming’s work sheds light on the process of socialization and the cultural norms men and boys have to abide by, while playfully alluding to the unspoken desire for sexual liberty that is inherent in any conservative society.

There’s a shameless innocence to his art; a characteristic that ultimately makes it provocative, and, at times, incendiary.