Ermo, Zhou Xiaowen’s 1994 movie, hits all the notes of 1990s China: accelerating collisions between the new and the old, the market’s destructive effects on the “traditional” family structure – especially the division of labor by gender – and runaway consumerism in a globalizing world. The film is undeniably tragic, not unlike many of the widely-known movies by Chinese directors of that time, which canvas the same themes. (Jia Zhangke’s The World in 2004, and of course Zhang Yimou’s contributions, all come to mind as representative of a 5th-generation-esque critical pessimism.)

But it is also a brutally exacting satire, and funny as hell. Ermo, a young woman in a rural Hebei village played by Liya Ai (also known as Alia), becomes obsessed with proving the scale of her own modernization, i.e. she wants to buy a big-ass TV.

It is hardly a theme unique to Chinese cinema. While difficult to imagine suburbanite, Westchester moms pounding noodles in the front yard, or selling them at the curb, the girth and resolution of the Jones’ flat-screen has surely been the topic of hushed and anxious gossip over the garden fence.

Maybe things aren’t so different in Hebei?

I like to think of Xiaowen’s film as a materialist American Beauty. The poverty is real, not spiritual, but the modern market-driven anxiety is the same, like the forlorn gazes of Hebei’s villagers as they peer into a wall of televisions, where a fit-and-trim woman (a Westchester mom, perhaps?) with ceramic white skin flaunts in the water. It is a take on the perverse methods used to export the American dream that seems both cynical and strikingly honest. Xiaowen’s is a humor which cuts to the core of the matter.

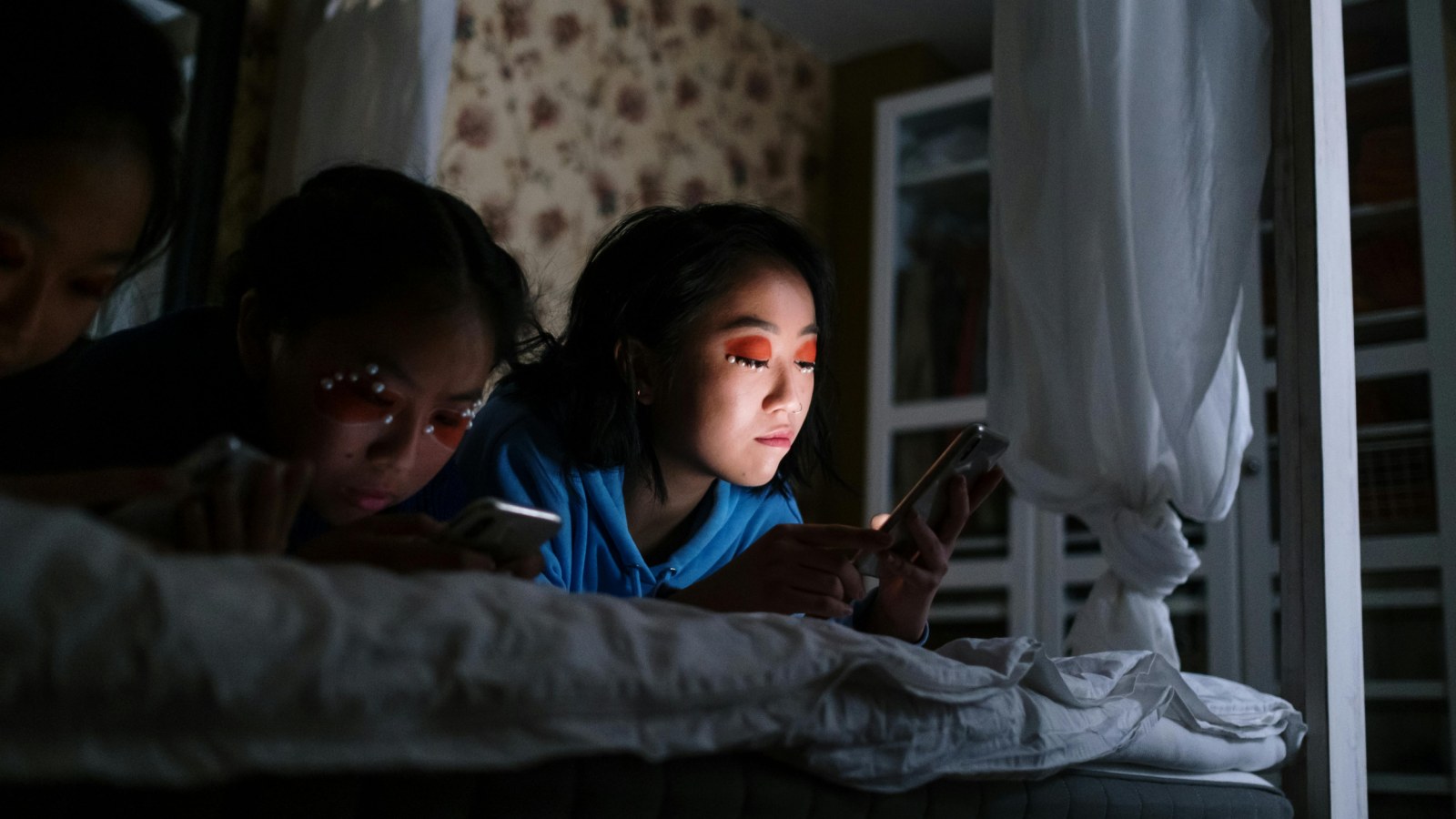

Ermo is worth your time for two magnificent scenes which return routinely, almost like chapter-markers: the shots of Ermo in the front yard manufacturing noodles, and those of Ermo-plus-villagers watching the television. In the first, she stomps and presses the dough as she sweats and pants in the pre-dawn dark. It is the hard physical labor which her neighbor (“Fat Woman”), who has the village’s first TV, would never do, and it is work her crippled, anachronistic husband cannot do:

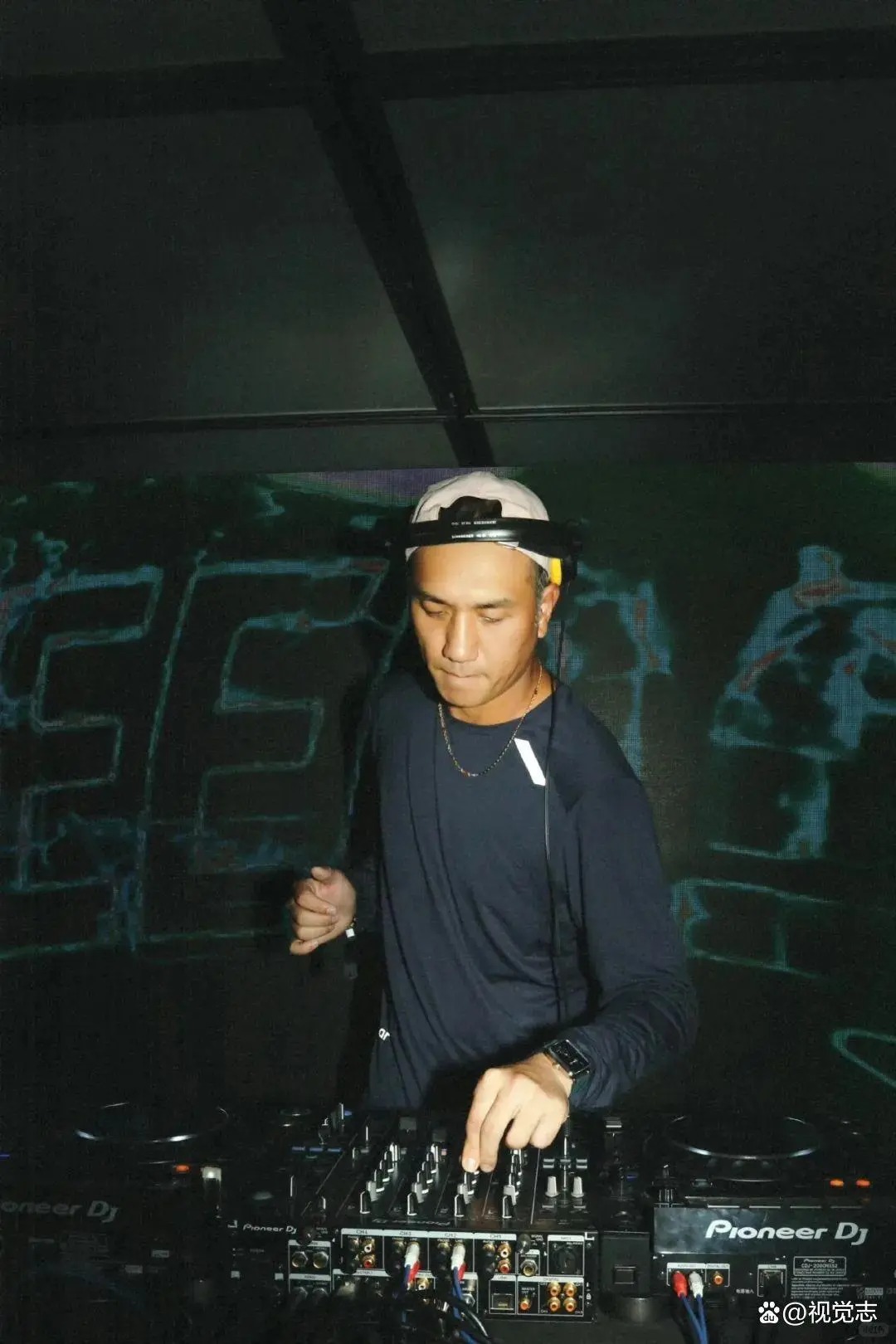

Then, there is Ermo and Co. in the local municipality’s electronics store, where she comes to lust after the 29-inch television for which she’s working herself to death. The “premodern” villagers are packed into the frame, staring right at or even through the television and into the camera (top GIF).

Xiaowen’s particular brand of brilliance is on display as he mines the intersection of consumerism and sexuality, marked by these two recurrent scenes. Ermo’s husband is a former Mao-era village official, called “Chief,” who is impotent in physical and market terms. A nostalgic but useless symbol of the past, he waits at home while Ermo embraces the market and falls in with her rival housewife’s husband, a market-savvy entrepreneur. (He has a truck.)

American reviews of Ermo’s extremely limited North American release, in both the New York Times and SF Gate, seem to miss its tragedy while praising its comedy. In the same way, these reviewers see Ermo’s television but they don’t see what it broadcasts: the American soaps and the white telecasters. When she hears a moment of Mandarin spoken on the broadcast, Ermo’s alarm reads almost like disappointment.

So Xiaowen works more than just a wry plot out of the television’s aura: he allows a moment for the Chinese villagers to look back, staring through the television’s promise of a Western modernity, right into the American cinema. He authors some type of silent critique, perhaps, of the global trends Ermo happily satirizes. It is certainly a shame that the film’s first American audiences missed it.

Director: Xiaowen Zhou

Release Date: June 8 1995 (United States)

Run Time: 98 mins

Source Material: Adapted from Xu Baoqi’s novella.

Awards: One Future Prize, Munich Film Festival (1995), Best Actress and Best Director, Shanghai Film Critics’ Awards (1995), Nominated for Gold Hugo Award, Chicago Int’l Film Festival (1995)

Where to watch: There is a Spanish-subtitled version on Youtube, or you can purchase the VHS (!) on Amazon.

| Column Archive |