A friend of mine sent me an article at The Conversation which argued the best way for the US to win trade concessions is for Donald Trump to call for a boycott of Chinese goods.

When we think of a boycott, we usually imagine consumers avoiding a particular product. Such boycotts have had varying levels of success.

A corporate boycott of a nation is much less common. To the best of my knowledge, a corporate boycott of a nation along the lines suggested here has not been attempted before.

Well, actually it has… in China.

As I wrote a few weeks ago, boycotts – both by consumers and companies – were an important form of resistance and action against the foreign powers in China in the early 20th century. On this date in 1905, the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce passed a resolution which called on both consumers and corporate entities to stop trading in American goods to protest US immigration policies and the poor treatment of ethnic Chinese in the United States.

Related:

American Business and Chinese Nationalism: Lessons from 1905Article Apr 16, 2018

American Business and Chinese Nationalism: Lessons from 1905Article Apr 16, 2018

May is a big month for anniversaries in China, and The Conversation article was coincidentally posted on May 4, a date which gives its name to one of the most famous mass movements in modern Chinese history.

While the May 4, 1919 demonstrations against China’s treatment by Japan and the Western powers at the Paris Peace Conference following World War I were the most visible – and best remembered – form of protest that spring and summer, Chinese commercial interests also organized a nationwide boycott against Japan.

As in 1905, Chambers of Commerce in Chinese cities urged their members and fellow citizens to stop buying Japanese products. Consumers stopped purchasing goods made by Japanese companies, an effort amplified by Chinese students who mobilized to shame and scare companies and individuals who defied the boycott. Workers refused jobs at Japanese-owned factories.

The May Fourth action followed another anti-Japanese boycott just four years earlier which protested the infamous 21 Demands made by the Japanese government against the shaky regime of Yuan Shikai.

Throughout the early 20th century, boycotts by consumers and companies in China targeting the economic interests of the foreign powers – especially Japan – became a part of the standard vocabulary of resistance.

Which makes it seem odd that the article doesn’t mention this history.

Related:

Karl Marx, Cai Yuanpei, and the Legacies of May FourthArticle May 04, 2018

Karl Marx, Cai Yuanpei, and the Legacies of May FourthArticle May 04, 2018

As my friend wrote in his email, calling for a boycott of Chinese products on May 4th and not discussing the history of boycotts in China is like “someone publishing a piece on countries declaring independence, having it run on July 4 — and not mentioning 1776.”

Leaving aside the history, a boycott of China is impractical. The Conversation article somewhat acknowledges this, arguing that for a boycott to work, European firms would need to find common cause with US companies against China.

For example, if a top U.S. luxury car seller such as Cadillac were to unilaterally boycott the Chinese market, then it would be giving up valuable market share to other rivals.

The key point is that many of those rivals are in Europe and have also been used and abused by Chinese companies and hence have a similar interest in finding a way to prevent them from stealing any more of their intellectual property.

If all Western luxury car makers jointly boycotted China, then this would be equivalent to acting as if a Chinese market didn’t exist. Clearly, profits would take a hit in the short run, but the long-term objective of ensuring that Western companies do business on a level playing field would be met.

There’s no question that joint US-EU action against China would be a very big stick but this assumes that US and EU interests in this matter are wholly compatible.

As Ferdinando Giugliano wrote on Bloomberg View last month:

Donald Trump’s slipshod approach to trade diplomacy risks pushing the EU into the arms of China. The EU’s main strategic interest in this fight is to ensure that the multilateral trading framework — including the World Trade Organization — survives. At the moment, this concern is most shared by Beijing, not Washington.

The plan proposed in The Conversation reminds me of a time once in Thailand sitting in a bar and watching two liquored-up tourists getting into a barroom shoving match. One guy was puffed up like a PCP-addled bantam rooster. They were both whining at each other until finally, Rooster shoved his opponent into a table spilling drinks and glass and bodily fluids over the folks sitting there, a group which apparently included Rooster’s travel companions. These same companions were not impressed when Rooster, rather than apologizing to them, started berating his friends: “Why didn’t you hit him? I had him down!”

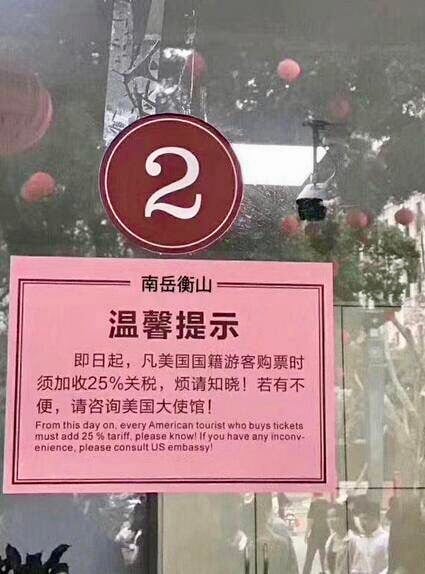

Given the diminishing supply of goodwill in Europe toward American leadership at present, it doesn’t seem likely the EU is joining this fight anytime soon, and China’s stance in the looming trade dispute with the US is a reminder of how historical memory continues to inform present-day perception and policy in Beijing.