Before the deluge of modern-day cafés and machine-extracted espressos and lattes, Malaysian coffee culture could be found in its kopitiams, or traditional coffee shops. These cafés can be traced back to the early Chinese immigrants who arrived in Southeast Asia during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The word “kopitiam” itself is a combination of the Malay word kopi (coffee) and the Hokkien word tiam (shop), reflecting their fusion of local and Chinese culture.

Setting up shop

Chinese migrants, predominantly from southern China, came to Malaysia for economic opportunities, working in tin mines, rubber plantations, or as traders. Over time, many of them established small businesses as a way to support their communities and earn a living.

By the early 1960s, kopitiams had become gathering spots where people from all walks of life could enjoy a simple meal, have a caffeinated drink, and discuss daily affairs. They were especially popular among the working-class Chinese population, serving dishes — for example, the classic trio of soft-boiled eggs, toast, and black coffee — that were affordable, comforting, and could provide sustenance for a long day of work.

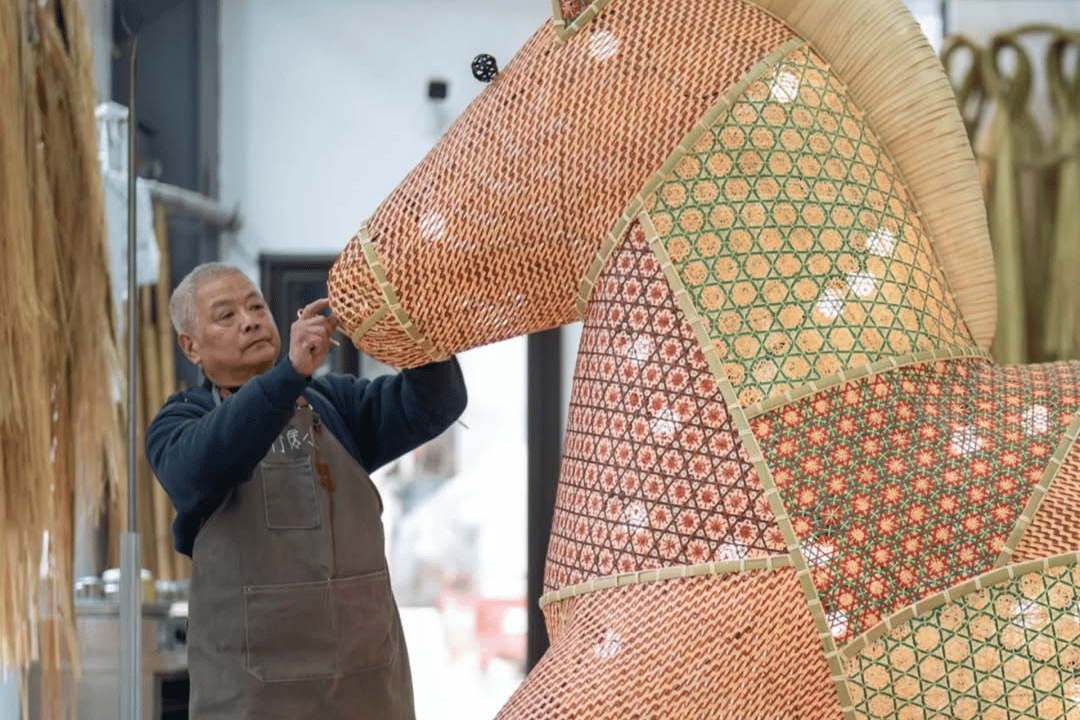

A significant contribution to kopitiam culture came from the Hainanese Chinese community. Arriving in Malaysia later than the first major wave of Chinese migrants, primarily in the late 1800s to the early 1900s, many Hainanese people found employment as cooks or helpers in British households and military cafeterias. After gaining skills and familiarity with Western cuisine, some would seize the opportunity to set up their businesses and introduce a fusion of local cuisine and European flavors to a wider clientele. To this day, the Hainanese are often regarded as the pioneers of the Chinese F&B industry in Malaysia, attributing their success to business acumen, discerning taste buds, and impressive cooking skills.

A family business

Staying true to Chinese familial values, the original kopitiams were operated almost entirely by families, with every member of the family contributing to the business. The system ran a tight ship: Parents and older relatives typically dominated the kitchen, brewing the signature coffee (Arabica coffee powder roasted in palm oil and margarine for a dark robust flavor) or preparing classic dishes like toast with butter and coconut jam (or kaya), curry noodles, and various pastries. Younger family members assisted with front-of-house tasks such as serving customers, cleaning, and taking orders.

When the time comes, the entire kopitiam structure, consisting of recipes, brewing techniques, business strategy, and the shop itself, is passed down from one generation to the next. This is why, despite advancements in coffee brewing machinery, the unique technique of straining coffee powder through a cloth filter is still used today. Similarly, instead of using commercial toasters, bread is slowly toasted over a charcoal grill to achieve a flaky, crunchy texture that feels almost impossible to replicate with modern equipment.

Keeping up with the times

However, as Malaysia embraces modernity, many traditional kopitiams are facing challenges when it comes to keeping the young generation in the business. Running such labor-intensive eateries isn’t an easy job, and the children of kopitiam owners are often encouraged to pursue higher education or enticed by high-flying corporate careers. Adding to that, the proliferation of Western-styled cafes and coffee franchises has made it difficult for traditional cafés to stay relevant, especially to Gen Zs and millennials with a taste for aesthetically-pleasing decor and quirky concoctions.

To overcome these roadblocks, the next generation of kopitiam operators are embracing their families’ legacies by staying true to their roots, while introducing modern touches, such as expanding menus to include trendy drinks, renovating shop spaces, and leveraging technology to improve operations. For example, many contemporary kopitiams offer cashless payment systems or market themselves on social media platforms like Xiaohongshu or TikTok to attract younger customers.

In the face of evolving consumer habits and grueling competition, these measures have given a new lease of life to many kopitiams. Several well-known kopitiams in Malaysia stand as testaments to the success of generational ownership and modernization. Nam Heong in the city of Ipoh is famous for its egg tarts and white coffee, and has grown from a small family-run shop into a recognized brand with multiple outlets, many of which are found in shopping malls.

A Hainanese kopitiam founded in 1928, Yut Kee in downtown KL remains a family-run institution known for its roti babi (a deep-fried sandwich stuffed with minced pork) and Hainanese chicken chop (a piece of crumbled chicken thigh served with fries and brown gravy). Though much of Yut Kee’s interior retains the old-school charm that customers have grown to love, it has since doubled down on technology, using online delivery platforms and digital payments to scale its business.

The future

As trendy cafes and contemporary restaurants mushroom around the country, the venerable kopitiam continues to stand the test of time as an important Malaysian Chinese institution that’s committed to adapting, but resilient in cultural preservation. After all, running a kopitiam isn’t just about serving food and drinks — it’s about maintaining a way of life and the values of hard work, family, and community spirit.

Banner image by Haedi Yue.