It’s morning in Tiananmen Square, and beneath gray smoggy skies, busloads of tourists from all over China wait (somewhat) patiently for their chance to see the desiccated corpse of Chairman Mao. The age of those waiting skews a bit older, and many of the folks in line say that this is their first trip to Beijing.

According to Chinese State media, over 200 million people have visited the Mao Zedong Memorial Hall since it first opened in 1977. The lines out front — which grow even longer during holiday weeks and around important dates such as the anniversary of Mao’s death in late September and Mao’s birthday on December 26 — suggest that Mao remains a powerful draw even in the era of Xi Jinping.

Beijing authorities are now hoping to bestow a bit of international prestige on the Memorial Hall by making a bid for Mao’s tomb — and 14 other Beijing landmarks — to join the list of World Cultural Heritage sites by 2035.

[pull_quote id=3]

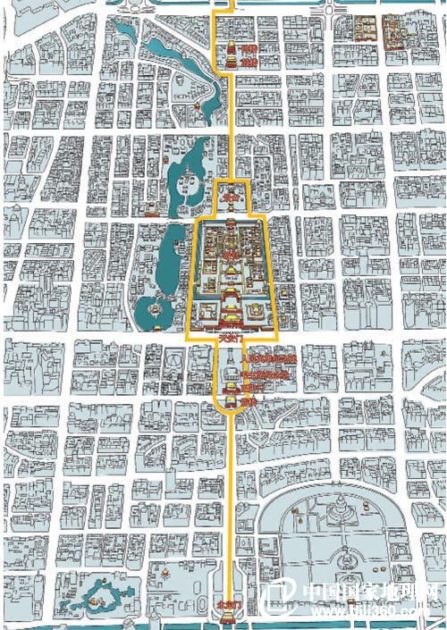

Most of the sites in Beijing’s application are along a single line running south to north through the heart of the capital. This Central Axis begins at the former site of the Yongding Gate, once the southernmost entrance to the city, and extends nearly eight kilometers down the middle of Tiananmen Square, the Forbidden City, and the hill known as Jingshan before ending at the Drum and Bell Towers.

Map showing Beijing’s Central Axis (source)

(A later “extension” of the Central Axis means this imaginary line also forms the center of Beijing’s Olympic Green.)

As part of the bid, the municipal government has announced plans to renovate hutongs and streets to create a buffer zone along the Central Axis, including relocating residents in an effort to “return the heritage sites to their original state,” according to Shu Xiaofeng, director of the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage. Short form: Folks in Beijing should be ready for more dramatic and sweeping “improvements” across a huge swath of central Beijing.

The decision to include sites of recent vintage including the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall and Tiananmen Square in the bid has sparked controversy. Beijing rights activist Hu Jia told Radio Free Asia, “the Monument to the People’s Heroes and Tiananmen Square aren’t suitable for inclusion in the World Heritage List because of their strong political associations.”

And then there is the question of Mao.

There have been sporadic rumors, some dating back to the 1980s and 1990s, that Mao’s body would be removed from his mausoleum. These rumors generally coincide with the periodic closures of the Memorial Hall whenever experts feel the need to freshen up Mao’s corpse. For example, in 2012 Peking University professor Yuan Gang suggested cremating the body and relocating the remains to Mao’s hometown of Shaoshan in Hunan.

Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping, who generally eschewed the grandiose personality cults favored by Mao, was cremated after his passing in 1997.

Next man up is likely to be Jiang Zemin, although the Beijing rumor mill has called time of death on the bespectacled octogenarian so many times that Jiang might be leery of an immediate cremation. If I’m Jiang, my will would stipulate putting me in a corner for a few days and requesting someone poke me with a sharp stick every few hours just to be absolutely sure I’m dead before I go in the toaster.

Xi Jinping, who seems to be developing a taste for personality cults, hasn’t begun planning his own tomb yet, but in recent years has put to rest any notion that Mao would lose his pride of place at the heart of China’s capital.

Mao’s image on Tiananmen, which faces his mausoleum

On the 120th anniversary of Mao’s birth in 2013, Xi Jinping led China’s top leaders in paying respects to Mao at his tomb and also chaired a symposium on Mao’s legacy. Xi called Mao a “great patriot” who “led the Chinese people to a new destiny” despite the mistakes that were made during the Cultural Revolution.

Nevertheless, it has been increasingly difficult to discuss those mistakes in recent years. Xi Jinping has been waging war against “historical nihilism,” a nebulous phrase which covers a range of offenses from denying the inevitability of the Communist Party’s leadership of China to looking too closely into darker chapters in the Party’s past. In the current ideological climate under Xi Jinping, Mao’s legacy seems relatively safe. (The legacy of Deng Xiaoping perhaps not so much.)

[pull_quote id=2]

Beijing’s bid for UNESCO status has been in the works for quite some time, at least since 2012. Whether it is successful is up to UNESCO, which runs the world heritage program and helps to maintain major cultural sites around the world. China currently has 53 sites listed, 36 of those are cultural heritage sites.

China has been seeking a larger role in UNESCO. Last year, Beijing lobbied hard for its nominee Qian Tang to be elected as the 78-year-old organization’s eleventh Director-General. The job ultimately went to Audrey Azoulay, who had previously served as France’s Minister of Culture. But China’s efforts to extend its influence into UNESCO received a boost when the United States announced it will withdraw from the organization at the end of this year citing concerns over the need for UNESCO’s fundamental reform, and its continuing anti-Israel bias.

[pull_quote id=1]

This is not the first time the United States has quit UNESCO in a fit of pique. In 1974, the US stopped its contributions to the UNESCO budget after the organization recognized the PLO, and in 1984 the US also withdrew from the organization, at the time also citing a perception of anti-Israel bias. The US rejoined in 2002 only to stop paying its dues in 2013. With the States’ tab set to exceed 600 million USD by the end of 2018, the Trump administration decided to again pull the plug on US involvement. This has opened a door for China.

UNESCO should consider China’s bid carefully. Historical sites like the Drum and Bell Towers or the Ancestral Temple and the Altar to Grain and Soil which flank Tiananmen (Gate) would seem like good candidates to join the Summer Palace, Forbidden City, and the Temple of Heaven on UNESCO’s list. But Tiananmen Square, which really only dates from the 1950s, and Mao’s mausoleum, built during the last days of disco, would seem to be a stretch.

Moreover, the fate of the Old Town of Lijiang and other UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites in China should be a cautionary tale for what Beijing has planned for the neighborhoods which fall along the city’s Central Axis. The transformation of Lijiang, a popular tourist destination in Yunnan Province, from an outpost of local culture into a honky-tonk circus of karaoke, cafes, and souvenir shops does not bode well for the neighborhoods of Beijing’s historic center.

Workers bricking over doors and shop fronts in July as part of an ongoing effort by Beijing municipal authorities to “improve” the historic heart of China’s capital.

The bricking up of stores and local shops around the Lama Temple and Jiaodaokou (with rumors that the area east of the Drum Tower may be next) appears to be the early phases of a plan which will radically transform Beijing’s inner city from a lively and organic urban community into a sanitized reimagining of history, sponsored by Starbucks and Coco Tea.

You might also like:

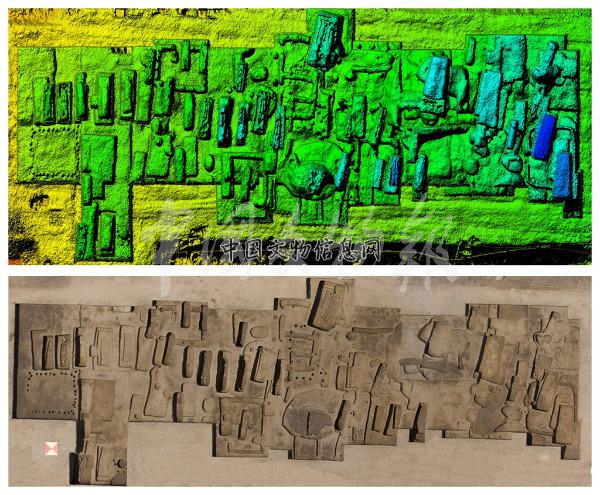

These Were China’s Top 10 Archaeological Finds in 2017Article May 10, 2018

These Were China’s Top 10 Archaeological Finds in 2017Article May 10, 2018

Drones to the Rescue, Restore Great Wall of ChinaArticle May 03, 2018

Drones to the Rescue, Restore Great Wall of ChinaArticle May 03, 2018

Karl Marx, Cai Yuanpei, and the Legacies of May FourthArticle May 04, 2018

Karl Marx, Cai Yuanpei, and the Legacies of May FourthArticle May 04, 2018