Warning: This post contains quoted language and historical images which are offensive, but are being used here to demonstrate the pervasiveness of certain racist tropes in discourse on Asia.

Is the CCP synonymous with China? Last week, Bill Bishop, the China watcher’s China watcher, took to Twitter and — as he sometimes likes to do — decided to mess with folks a bit.

It is a mistake to talk about “Chinese influence”. That is a dangerous conflation that can spark anti-Chinese sentiment. The issue is “Chinese Communist Party influence operations”. Warning against those is not anti-Chinese. Don’t be lazy, and don’t let CCP media conflate the two

— Bill Bishop (@niubi) December 17, 2017

It’s an interesting question. The New York Times decries “Russian interference in the 2016 US elections.” Any number of media outlets around the world complain about “American influence.” What’s so problematic about saying “Chinese influence” in the context of international affairs?

For starters, history.

There is a long and regrettable legacy of stupid white folk understanding threats from Asia in purely racial terms. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, almost every conflict between “West” and “East” ultimately became about race. The influential editor Horace Greely in response to labor disputes in the American West and in support of a Chinese Exclusion Act wrote:

The Chinese are uncivilized, unclean, and filthy beyond all conception, without any of the higher domestic or social relations; lustful and sensual in their dispositions; every female is a prostitute of the basest order.

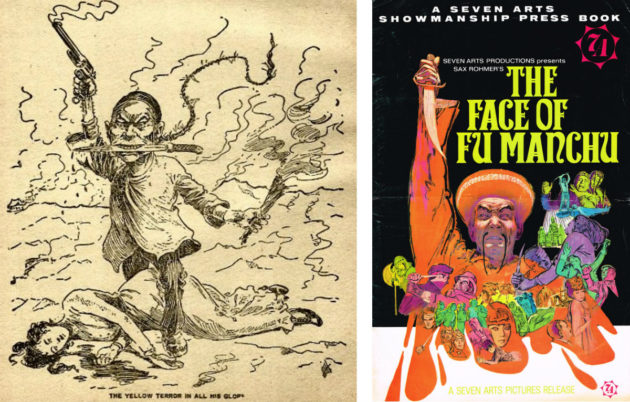

The “Yellow Peril” was a broad basket of imagery, clichés, racism, and hysteria which transcended any one nation. The language of racial war included a treasure trove of cultural, social, and sexual anxieties that found expression in literature, print media, pop culture and, later, film and television.

Turn-of-the-century confrontations between ascendant nation-states in East Asia and the colonial powers of Western Europe internationalized this language of racial conflict.

Kaiser Wilhelm II sent a message to his troops during the Boxer War of 1900 ordering them to show no mercy as they avenged the death of Baron Clemens von Ketteler, Germany’s minister to the Qing Empire. Baron von Ketteler had been one of the first diplomats killed by the Boxers.

When you come before the enemy, you must defeat him, pardon will not be given, prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands will fall to your sword! Just as a thousand years ago the Huns, under their King Attila, made a name for themselves with their ferocity, which tradition still recalls; so may the name of Germany become known in China in such a way that no Chinaman will ever dare look a German in the eye, even with a squint!

Yeah, Kaiser Willy was kind of an ass, but I’m guessing the irony of encouraging his troops to model their behavior after an Asian invader of Europe wasn’t unintentional and, as a bonus, he also helped the German troops adopt a fun new nickname which wouldn’t be going away anytime soon.

It wasn’t only European autocrats who thought this way. US policy during World War II differentiated the campaigns in Europe and those in Asia along racial lines. As historian John Dower argued in his influential 1986 book War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War, the war in Germany was against evil individuals — Hitler and the Nazis, Mussolini’s Fascists — which allowed for the possibility of the “Good German.”

There were no “good” Japanese. The War in the Pacific wasn’t fought against Japanese militarists, and propaganda films and posters from the era are graphic in their depiction of the Japanese as a race. These posters draw heavily on Yellow Peril anxieties, either portraying Japanese soldiers as subhuman insects or super-human sexual predators. Subtle, it was not.

As the Cold War descended and Japan shifted from enemy to ally, a new threat emerged: Communism. As Robert Bickers writes in his recent book Out of China: How the Chinese Ended the Era of Western Domination, during the 1950s and 1960s, “Old narratives and fears about China were given new life, and the ‘Yellow Peril’ was dressed anew as a ‘Red’ one.”

Dr. Fu Manchu had become Dr. No.

There are good reasons why we need to be careful when discussing “Chinese influence.” The idea comes freighted with a great deal of historical baggage, and it becomes too easy to slip into uncomfortable tropes. “Civilizational conflict” becomes a dog whistle for “racial war.”

The idea of “Chinese influence” comes freighted with a great deal of historical baggage, and it becomes too easy to slip into uncomfortable tropes

Bill Bishop’s tweet isn’t just about how a discussion of “Chinese influence” might devolve into race-baiting or that coded language plays into the hands of the Chinese government and the state-controlled media who are quick to claim “racism” whenever the subject emerges in the international press. Bishop is also taking that same sharp stick and using it to turn around and give the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party a good poke of their own.

Differentiating the “CCP” from the “Chinese people” sets a sticky wicket for the Chinese government.

The Party’s legitimacy rests, in part, on its assumed role as the sole representative not just of the Chinese state, but the Chinese nation and, increasingly, Chinese civilization writ large. Critics of CCP policy are frequently accused of “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people.”

Party theoreticians and propagandists are hypersensitive to any attempts to separate the party from the people. Doing so undermines the CCP’s very raison d’etre and sets up the possibility that the Chinese nation or people could have a future or identity separate from that of the Party. This is dangerous ground for a Leninist Party-State.

Fundamentally, I agree with Bill’s larger point. Terminology matters. Words count. Xi Jinping is not China’s President. He’s the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. It is not the Chinese people (as a nation or especially as a “race”) who are spreading their influence — it is the work of the Chinese government, as directed by the Chinese Communist Party.

Does that make it comparable with the spread of “American influence” around the world? Sure. But like a lot of things, past discourse affects how we use language in the present. Saying “American influence” simply does not come loaded with the same legacy of racism and racist language as “Chinese” or “Asian” influence. That’s why we need to be a little more careful with how we choose our words.

(And if doing so also subtly tweaks hardline ideologues in the CCP, well then that’s just a bonus.)