If you’re a writer, the word “thesaurus” probably brings to mind the crucial crutch on which you lean every time your brain gives up on finding good words (fairly often). If not, you might have last cracked one in high school or college, but otherwise this verbal resource remains a relic of your past. For London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, the thesaurus provides the conceptual framework for an ambitious new project that’s been in development since 2016, and launched a pilot phase last month: the Chinese Iconography Thesaurus.

Combining images from the collections of the V&A, the Met in New York and the Palace Museum in Taipei, the CIT is a work in progress that aims to create a “conceptual map” of Chinese visual history from the 10th-19th centuries, according to Hongxing Zhang, the project’s chief editor and a senior V&A curator. The goal is “to give people” — Zhang has an audience of researchers, curators, and students in mind — “an opportunity to explore the complex relationships between images and ideas and abstraction,” he says, “so [that] people will understand more about the significance or the meanings or layers of meanings of the images in Chinese culture.”

I spoke with Zhang after the launch of the CIT about what the thesaurus format offers in contrast to more traditional, hierarchical structures favored by other institutions, what use cases he has in mind for the project, and what differences in attitude toward cultural heritage exist between institutions in China and Europe:

Hongxing Zhang speaks at a conference in Beijing, October 13, 2019

RADII: Why choose the word “thesaurus” for this project? This has more of a verbal than a visual connotation.

Hongxing Zhang: Right. The first [reason] is that we like to get this visual, image database underpinned with vocabulary. And the thesaurus is a special type of controlled vocabulary, which is not the typical indexing practice in the museum environment. But because of our idea of building a more complex relationship between the vocabularies, between the terms, the concepts, after researching on controlled vocabulary options, we thought the thesaurus was the best one for our purposes.

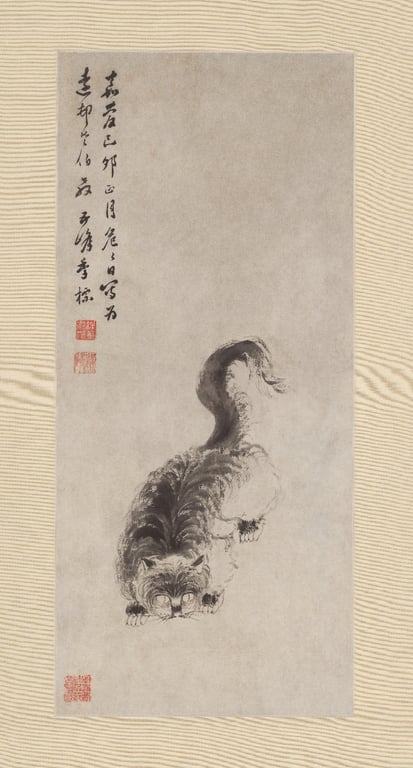

My understanding of “thesaurus” is it’s an advanced classification scheme. The Warburg Institute’s photographic collection [by contrast] uses a typical classification scheme, which is hierarchical, a bit like taxonomy for plants or animals. But a thesaurus is not only a hierarchical taxonomy but also has two other features: an equivalent relationship and an associative relationship. For associative relationships, basically it allows the two terms to have a symbolic relation. For example, the cat and the butterfly — these are two words that relate to longevity in Chinese culture. So “longevity” is one term, and “cat” and “butterfly” are two others. We link these terms in this type of associative relationship. The thesaurus [format] allows us to build this system, or network, of term relationships.

Cat by Ji Biao, 1819 (image courtesy The Victoria and Albert Museum)

At a recent conference in Beijing, you said that “arranging visual materials according to a chronological or geographical order is inadequate for recording and accessing their iconographic information.” When I think about Chinese iconography, the first thing that comes to mind is the sheer density of the source material. If you’re eschewing chronological history or geography, what alternative taxonomies or schema are you trying to implement?

First, I have to clarify that in this image database, underpinned by the thesaurus and the terminology, we focus on the subject matter — the contents of images, of objects. And this is a very specific type of documentation. Other aspects — like chronology, dating, the place of production and [other] geographical features — are documented in the museum and the library environment. So what we do is to link this iconographic database to the individual museum’s collection database.

There is a facility for us on our website to link this iconographic documentation to the original documentation made by the museum where the object is collected. So, this iconographically catalogued image database does not provide the information about the place, about time, about other physical or stylistic features. But those aspects of documentation exist in museums, in the collection database.

An Itinerant Daoist Priest, Unknown, ca. 1790 (photo courtesy The Victoria and Albert Museum)

The other thing is that we define the Chinese Iconography Thesaurus by time as well. We only focus on the period from the 10th century to the end of the 19th century. We don’t push beyond, say, pre-10th century periods in China for various reasons. One is that before the 10th century, Chinese art is required to be studied, in many cases, in the context of archaeology, which is quite different from the materials after the 10th century. Basically, we focus on objects which are handed down from generation to generation through collectors and collections. And we focus on objects, print culture and illustrations, printed illustrations, decorative arts.

What form will the CIT take? Right now on the site you can click on different categories and find images that way, and there are also some large meta-images at the bottom that you can zoom in on in fine-grained detail. Is this the format that it will keep in the future?

Yes, that’s the current format it has. But in the future, we will provide more network analysis facilities. For example, we’ll have filters for artists and for periods, or perhaps geography, which will provide more layered information about iconography. So, for example, in the Jiangnan area, what kind of subject matter is more popular in a certain period of time or within [the work of] one artist? What changes in subject matter do we witness?

But basically, this website provides a visual thesaurus. So, it has this hierarchical structure of the concepts which are illustrated by the images, and which reflect or depict the Chinese conceptual world during this time frame, and give people an opportunity to explore the complex relationships between images and ideas and abstraction. So people will understand more about the significance or the meanings or layers of meanings of the images in Chinese culture. It’s a kind of conceptual map. That’s what we’d like to present, to explore.

You might also like:

China’s “5,000 Years of History”: Fact or Fiction?The recent elevation of the 5,300-year-old site of Liangzhu to UNESCO World Heritage status revives an old debate about modern China’s historical narrativeArticle Jul 15, 2019

China’s “5,000 Years of History”: Fact or Fiction?The recent elevation of the 5,300-year-old site of Liangzhu to UNESCO World Heritage status revives an old debate about modern China’s historical narrativeArticle Jul 15, 2019

Obviously, this is going to be of interest to researchers in various fields. To what extent has it been designed to be accessible by lay people or amateurs?

The current format, we hope, is relatable to the general public or university students. Particularly, we have in our mind that this kind of database will be very useful for university students who want to find a topic for their essay or their coursework. For example, someone wants to find how the Chinese represent time — that’s quite an abstract concept. She could go to this website, go to the sample image collection, to browse time, that concept, and see what kinds of images would come up and the different categories of time, and the Chinese definition of the periods of time and instruments for measuring time, which give more ideas for the student to explore what topic she or he wants to write about.

The other use would be museum visitors, or even museum professionals. I was told by one of our colleagues that this is very useful in the research phase of curating a thematic exhibition. If you choose, let’s say, Romance of the West Chamber (西厢记), that opera, as your exhibition theme, you can search the database to find relevant images across collections.

It could also be useful for professionals in creative industries. If you’re interested in the hidden meanings of objects, or plants or animals in Chinese culture. In our daily life in the museum, we are [often] contacted by designers or advertising companies asking those questions.

A porcelain dish painted in overglaze enamels, 1662-1772 (photo courtesy the Victoria and Albert Museum)

All of the images currently in the Thesaurus come from the V&A, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the Palace Museum in Taipei. Are there any other institutions that are looking to become involved? Are you trying to promote the involvement of mainland Chinese institutions?

We’d like to involve more museums in the next phase of this project. But for the three [mentioned above], this is a pilot study period. Because of the limitation of time and also the openness of museum collections in the world, we selected these three institutions. The Met and the Palace Museum in Taipei all put their images — some of them quite high-res images — online as an open access resource, meaning that anyone can use them, even for commercial purposes. In the future, I think our criteria for including museum collections is to first see if their database is open access — we will prioritize those.

For mainland Chinese museums, one major issue is that open access is still a practice and a concept to be [better] understood. We hope in the future we will involve mainland Chinese museums, but it will take time.

Related:

Chinese Museum Turns Ancient Relics Into Emojis, Becomes Internet HitA museum in China has earned viral status online after releasing a set of emojis based on relics and artefacts from their collectionArticle Mar 26, 2019

Chinese Museum Turns Ancient Relics Into Emojis, Becomes Internet HitA museum in China has earned viral status online after releasing a set of emojis based on relics and artefacts from their collectionArticle Mar 26, 2019

Based on your experience working at the V&A, what would you say are the major differences in attitude or philosophy about cultural heritage in the UK vs. China, or among different institutions with which you’ve interfaced?

The one striking difference is access. In the V&A, really in general in European and American cultural heritage institutions, we really encourage and emphasize openness. Open the sources to the public, to the society, to everyone. And that is, I think, a different attitude from what I perceive in China or in East Asia in general.

In the V&A or other institutions in Europe and America, professional institutions treat collections, objects, as a source for inspiration, for creativity. The more open, the more creativity will come out of that process of studying, looking at, and researching the objects. That’s the philosophy, the fundamental thing I’ve experienced working in such institutions.

Porcelain vase painted in underglazed blue, 1690-1700 (photo courtesy The Victoria and Albert Museum)

But in China, for one reason or another, museums and cultural institutions treat objects in the collections as something sacred, as something to be protected, to be preserved. Not just for contemporaries, but for posterity. They use the word “cultural relics.” That is the slight difference in terms of attitude toward collections, towards objects, towards, really, the relationship between the objects and the audience. This attitude may come from recent history, what Chinese cultural heritage institutions experienced in the sad history of objects being destroyed or illegally exported to other places. So in China, and in East Asia in general, they have a more protective attitude toward the objects in their care.

Get lost in the Chinese Iconography Thesaurus here.

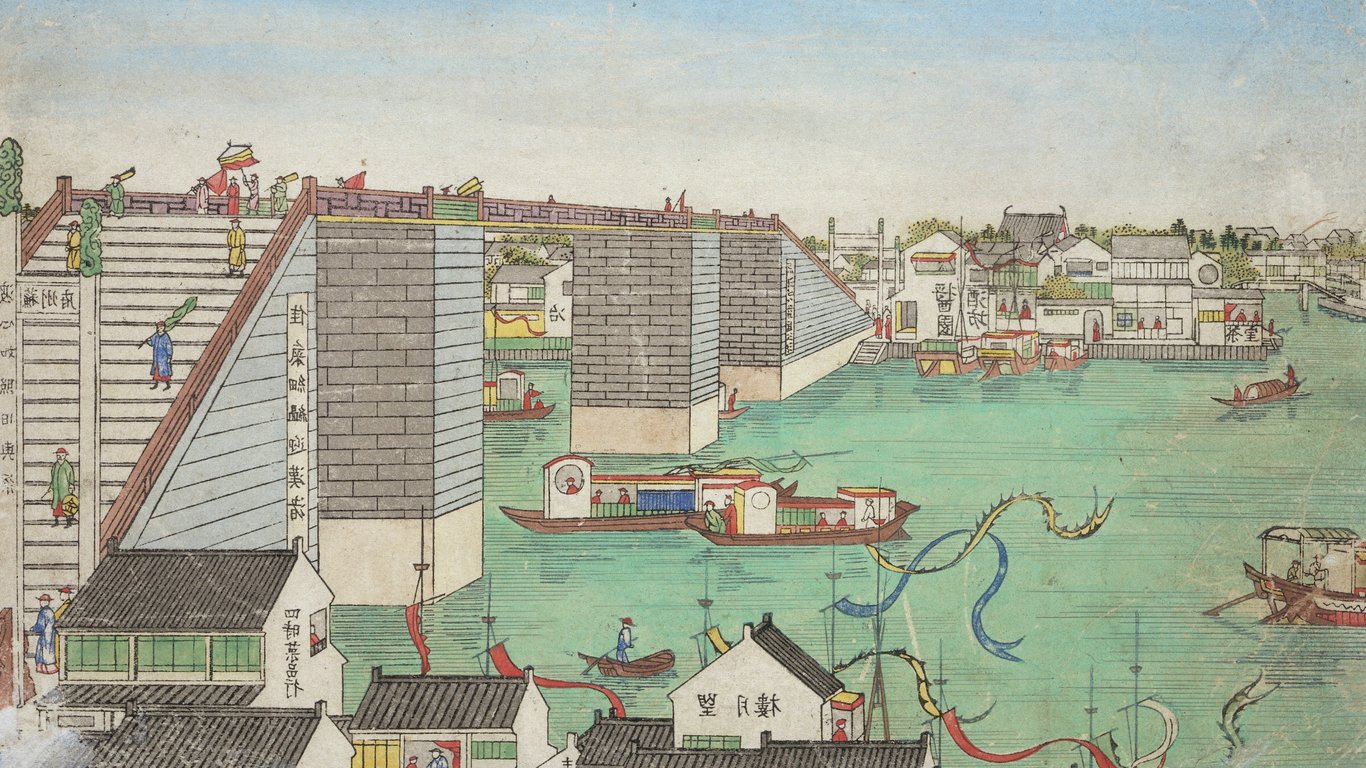

Cover photo: Perspective Print Depicting Wannian Qiao Bridge in Suzhou, 1750-1800 (photo courtesy The Victoria and Albert Museum)