[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Zhibo is a weekly column in which Beijing-based American Taylor Hartwell documents his journey down the rabbit hole of Chinese livestreaming app YingKe (Inke). If you know nothing about the livestreaming (直播; “zhibo”) phenomenon in China, start here.

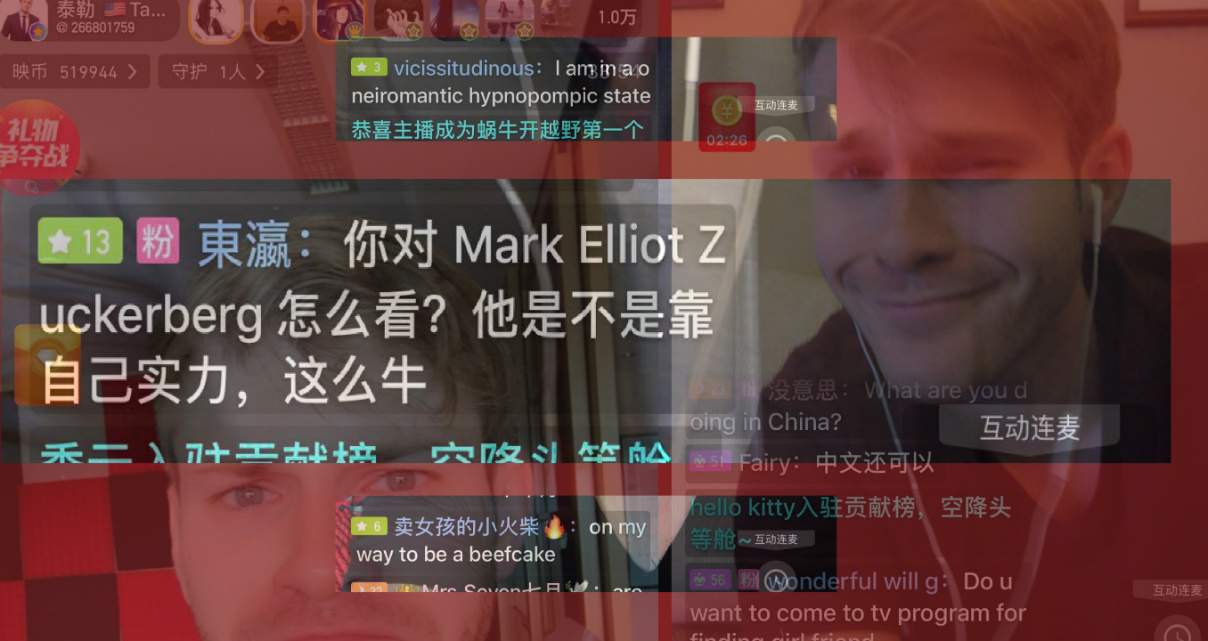

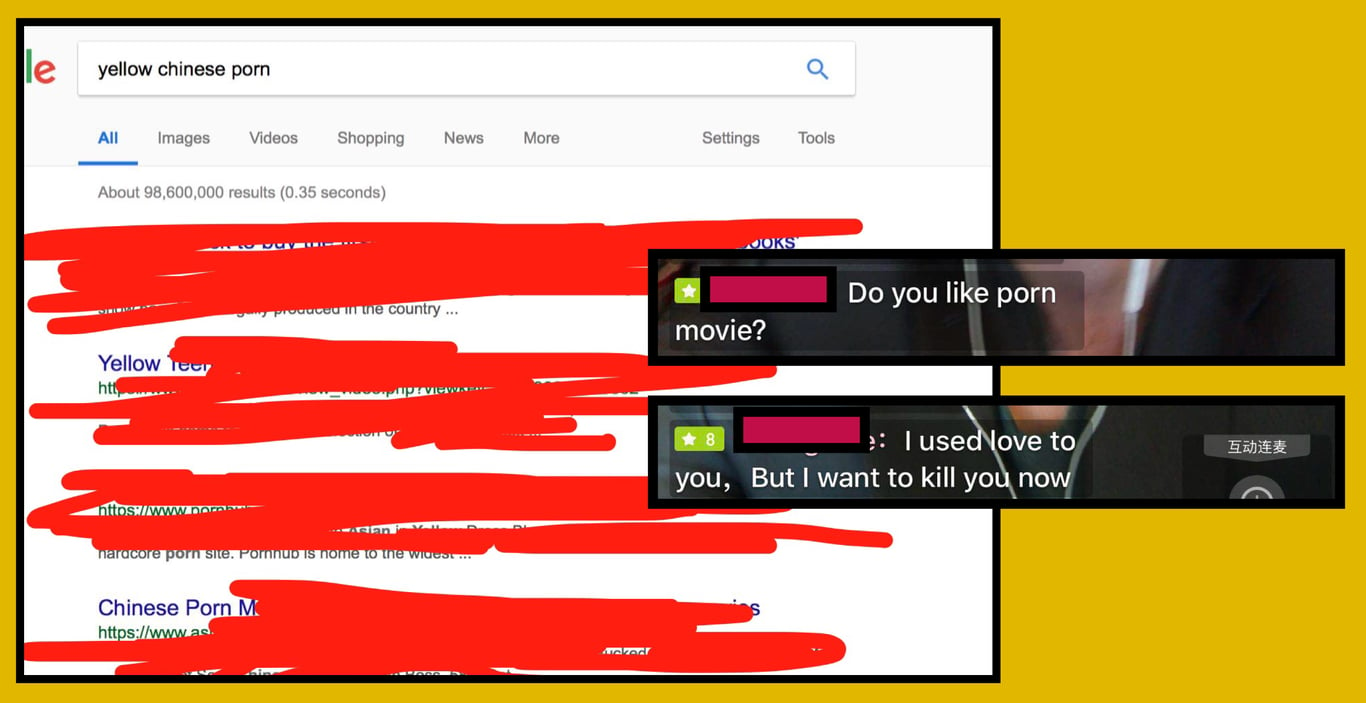

Questionable Proposition of the Week If you geve Me dome doarls I Can sellipe with you

The best I can assume here is that this was meant to read: If you gave me some dollars I can sleep with you. Which, if I’m being honest, is a pretty presumptuous hypothetical.

But then again, perhaps “sellipe” is some kind of newfangled spin class (pronounced SELL-EE-PAY) popular in France and “doarls” is the hottest new cryptocurrency and the only form of payment Sellipe coaches accept. One never knows.

My New Favorite Thing Watching the Audience Argue About Chinese

Language battles

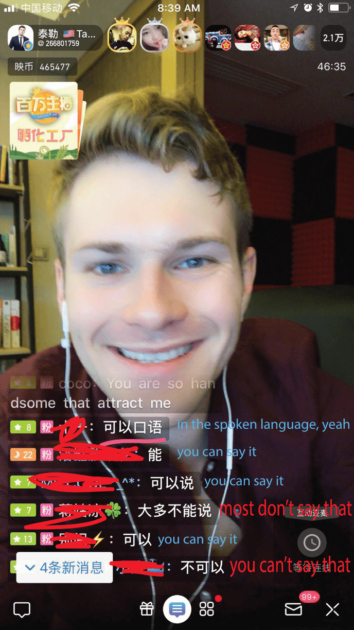

One very useful thing about chatting with 20,000+ Chinese people every morning is that it’s pretty easy to crowd-source the answers to language questions.

At least, most of the time.

Last week, I had the temerity to ask whether or not I could use a certain word in a certain context, and woah it was like I had brought that black/blue/gold/white dress picture into the streaming room. It started with choruses of “yes you can” and “no you can’t” and quickly escalated to so much yelling (well, there’s no such thing as capital letters in Chinese, but it certainly *felt* like yelling) that I quickly shut the stream down lest I risked the ire of any trigger-happy censors.

So while I didn’t get the answer to that particular question, I did get something new to think about: how deceptively tricky it can be to explain something you’ve never really questioned before.

I’m a big fan of the idea that being able to explain something simply and clearly to a beginner is a good litmus test for how well you understand it yourself. This is particularly true of questions about your own native language – there are so many little rules and exceptions and complexities that we have all just intuitively understood from childhood and would struggle to explain to someone unfamiliar with English.

Be honest – could you, without a trip to Wikipedia, explain:

- Why Americans call football “soccer”?

- Why “tomb” and “womb” sound like “toom” and “woom” but “bomb” doesn’t sound like “boom”?

- Why “a big old friendly dog” sounds perfectly normal but “a friendly old big dog” sounds kinda weird even though both sentences are grammatically correct and mean the same thing?

- what the actual f@#k the word “literally” means these days?

- irony?

- Why we write “queue” and only pronounce the first letter?

Our language is weird

But the thing is, most reasonable native English speakers look at stuff like that and think, yup, those are strange things about English that I probably couldn’t explain, then go back to whatever they were doing before a stranger on the internet accosted them about their lack of explanatory gifts.

We – Americans, at least – have a lot of flaws, but overall I’d say we don’t tend to be overly precious about English. Grammar Nazis on forums abound, sure; but I don’t feel like most of us have any particular pride in English in the Platonic noble lie sense. It’s the language we speak and we’d obviously prefer other people to speak it too, but we don’t really make the claim that it in and of itself is somehow special.

Chinese, however, is a different story. Insomuch as one can accuse a *language* of having an attitude, this is a language that makes French look humble – I rarely get more than a minute into a question about Chinese without being told how 博大精深 (boda jingshen, an idiom that means to have broad and extensive knowledge, sometimes referring to people or scholarship, but often applied to a language or culture as a whole) it is.

[pull_quote id=1]

And the thing is, I’m not saying that Chinese is NOT a 博大精深 language, just that my simple question about pronunciation didn’t necessarily merit a lecture about how over my head everything is.

Again, there’s nothing wrong with being proud of your linguistic skills – especially if you had to spend the first 18 years of your life copying characters over and over again to acquire them. But in China, the language itself is treated (by some people) like the one true god before which all else must kowtow (or 磕头) in submission.

But while it’s perfectly-well-understood by everyone that a foreigner will never grasp the complexities of the emperor’s language, it’s a lot less commonly accepted that between the billion native speakers (at least, native on paper) there will occasionally be differences of opinions on word choice, meanings, etymologies, etc. Hence, massive fights breaking out when Chinese speakers can’t give the foreigner the one true answer to his Chinese question.

So although I generally have a pretty positive symbiotic sort of relationship with the Inke audience, I must admit to experiencing just a bit of schadenfreude when people start criticizing each other’s Chinese instead of my own for a change.

Weird Thing That Keeps Coming Up A Fascination with Eye-Rolling as Some Sort of Talent

When I started streaming on Inke, I figured that keeping the open displays of contempt to a minimum would probably be pretty important to building an audience. Which is a shame, because – I don’t know if I’ve mentioned this before – people tend to ask the same dumb questions over and over and over again.

[Editor’s note: you have mentioned this several times now and it’s starting to get “ironic”]

But every once in a while, someone asks if I’ve managed to figure out chopsticks after three years in China or tells me that cold water will shorten my lifespan or asks if Americans know what “livestreaming” is (because of course, China invented it!) and I throw out the kind of eye roll that would lend genuine credence to the age-old concern of one’s face getting stuck like that.

The audience reaction is just the damnedest thing, though. Almost every time, I get a few dozen of these:

哈哈,你的翻白眼好厉害

haha, your eye roll is so 厉害

“厉害” is a truly odd word. It sounds like “lee-hi” and the literal translation would be “severe harm” or “strict evil” or something like that, but together it technically means “fierce” like a tiger or “terrible” in that “Lord Voldemort did great things… terrible, but great” kinda way. But that’s all a moot point because the way people actually use 厉害is to mean something is good. Or great. Or talented. Or cool…or epic, awesome, amazing, neat, super, super-duper, mind-blowing, or just about any other word that you might use to complement someone or something.

And people use it to describe EVERYTHING. Your Chinese is 厉害. The kung fu panda is 厉害. That explosion was 厉害. You swim so 厉害, you talk so 厉害, the teacher is 厉害, the students took the test so 厉害, you cook food so 厉害, the food you cooked is 厉害, your use of chopsticks (woah, you can use chopsticks?!?) is 厉害.

And apparently, my eye-rolling abilities are 厉害. I’ve tried to push back and point out that rolling your eyes is just about one of the simplest and effortless physical actions there is, but people keep saying it. Some people have attempted to make the case that they’re complementing the, erm, “believability” with which I roll my eyes. Because, you know, I’m just acting and not really annoyed.

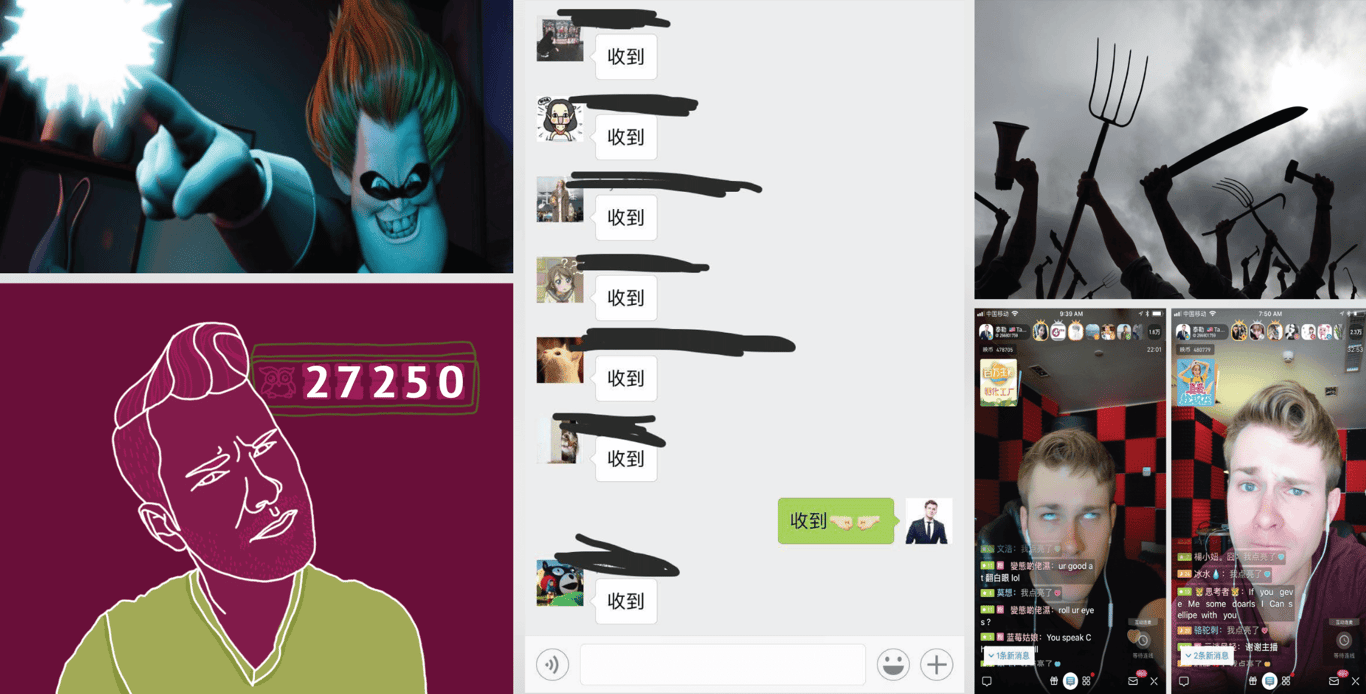

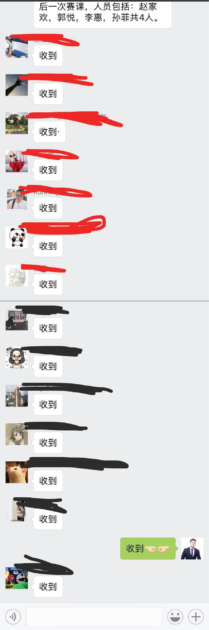

Setting aside for now why my audience seems to be impressed with the art of eye-rolling, 厉害 bothers me for two reasons. First, for all the complexity and artistic nature of Chinese characters, the actual spoken language can be almost scarily Newspeak-y. If things are good, they are 好 (hao, pronounced how). If they’re great, they’re 很好 (very hao), and if they’re excellent they’re 非常好 (really really hao). If they’re bad, they’re 不好 (no hao), if they’re… you get the point. Or, just take a look at how the members of a group chat respond to messages:

Pictured: me, trying to be a special snowflake

厉害 is a classic example of this. Basically, it’s 厉害 for anything on the excitement/talent end of the compliment spectrum and 辛苦 (laborious bitterness, or xinku) for anything on the hard-working end. But you know what? Americans are no strangers to overusing words. Just ask “literally” or “epic,” two perfectly good words the internet has ruined for us.

What REALLY bothers me about 厉害 is how it gets applied to everything – even my dumb eye-rolling.

To paraphrase Syndrome: When everything is 厉害, nothing is.

You might also like:

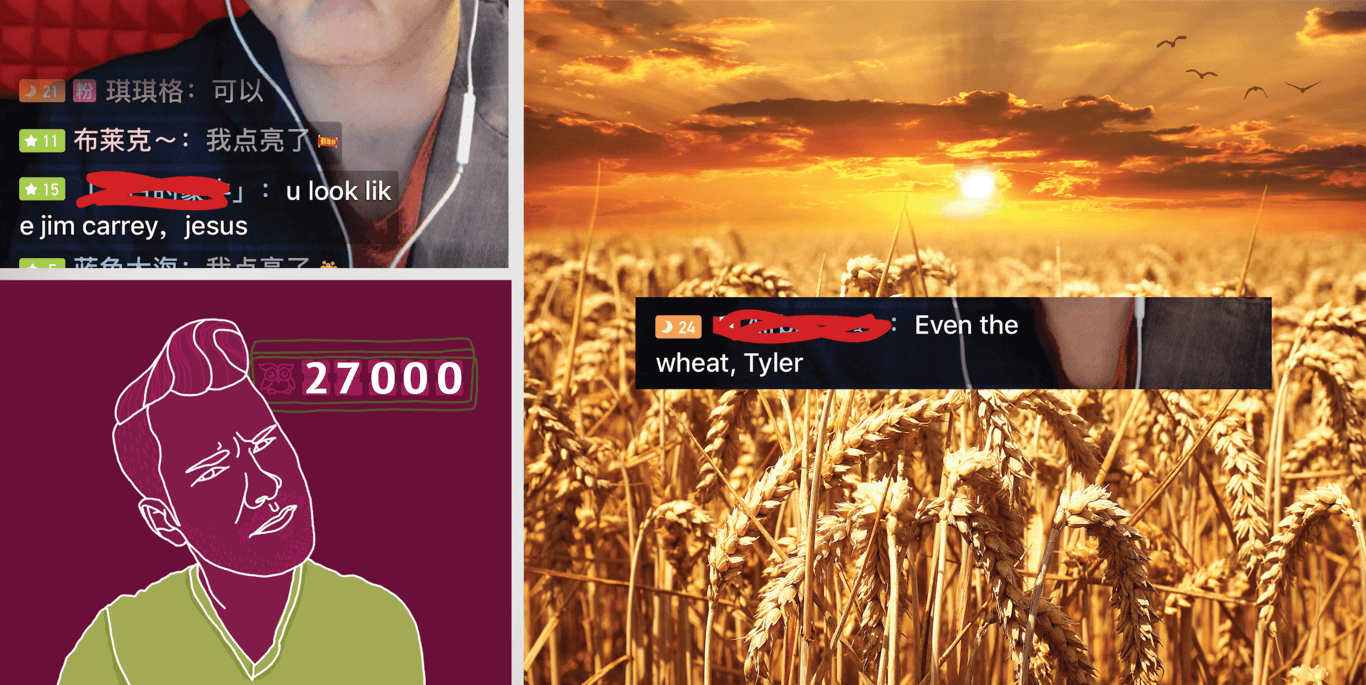

Zhibo: Wandering Fields of High-Tech Wheat with Jim CarreyArticle Apr 16, 2018

Zhibo: Wandering Fields of High-Tech Wheat with Jim CarreyArticle Apr 16, 2018

Zhibo: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Livestreaming in ChinaArticle Apr 10, 2018

Zhibo: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Livestreaming in ChinaArticle Apr 10, 2018