Describing postpost’s essence in a single word is challenging, but one term that comes to mind is “discomfort.” This is a space that’s designed to provoke. Nestled in an alley near a residential community in Beijing’s Sanlitun neighborhood, home to embassies and upscale shopping, the store’s latest location displays a sign at the entrance: “Achtung sie verlassen jetzt West-Berlin” (Attention! You are leaving West Berlin). Stepping inside, you will encounter an ambivalent text from Franz Kafka in the small foyer and the immediate embrace of loud techno music from the speakers. Your eyes are greeted by roughly polished walls, towering mushroom sculptures, church pew-like hardwood seats, and a massive priest’s chair. Despite serving coffee, this is not a place for leisurely afternoons.

While perusing the predominantly English bookshelf and flipping through magazines from Japan or Germany on topics like gender or AI, you may sense the presence of others in the store, or perhaps the barista’s watchful gaze. Ascending the stairs connected by a cold metal bannister dotted with tennis balls, just as you begin to relax by examining necklaces made from wig hair or earrings crafted from old CDs, a gasp may escape your throat as the price tags (more than 1000 RMB) drain the last bit of air from your lungs. In that moment of shock, you might be tempted to characterize postpost as simply an absurd or expensive store opened by fu’erdai (富二代, the Chinese equivalent of trust fund kids, literally translating to rich second generation).

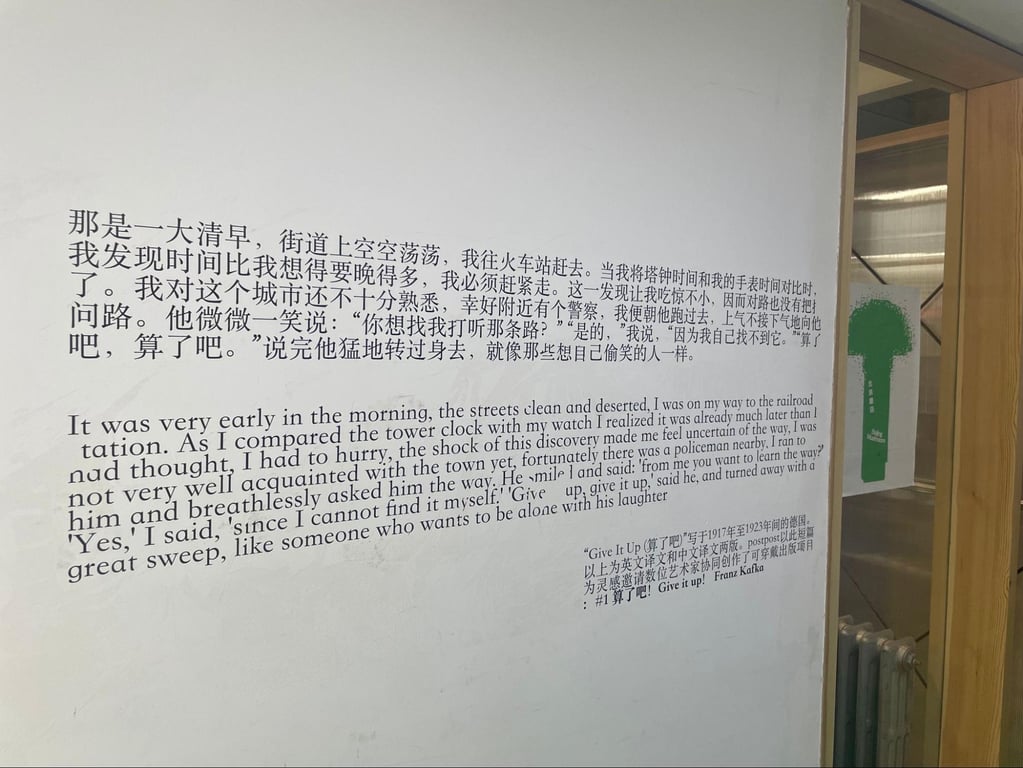

A small sign on top of the door stating “Achtung sie werlassen jetzt West-Berlin” (Attention! You are now leaving West Berlin).

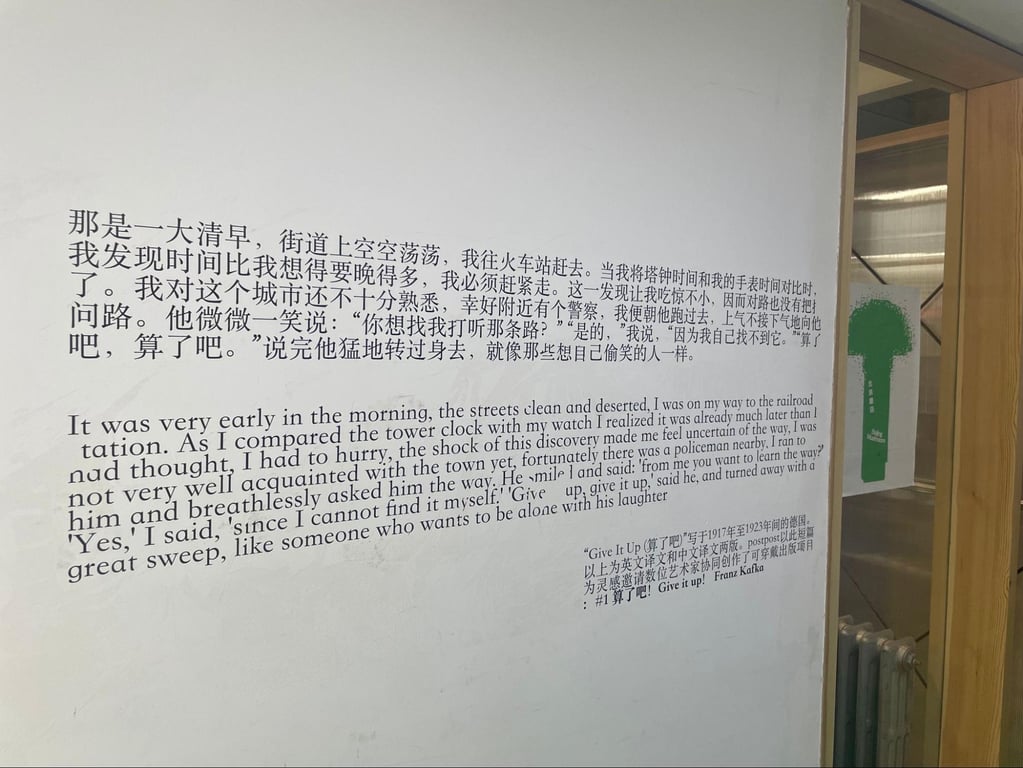

The aforementioned Franz Kafka text. postpost collaborated with an artist to make ready-to-wear pieces inspired by the quote.

But Xiao Yong, postpost’s co-owner, is opposed to such a tag. He is a quiet presence, keeping to himself until someone comments on the music, or artists that pique his interests. But he’s more or less an online celebrity within China’s underground culture community, where he’s known as THE indie art bookstore owner. He speaks firmly and is prone to elaborating through stories, the perfect combination of pathos and ethos. “If you can’t at least intrigue customers about the books you sell, you’re not competent as an owner,” he once said in an interview.

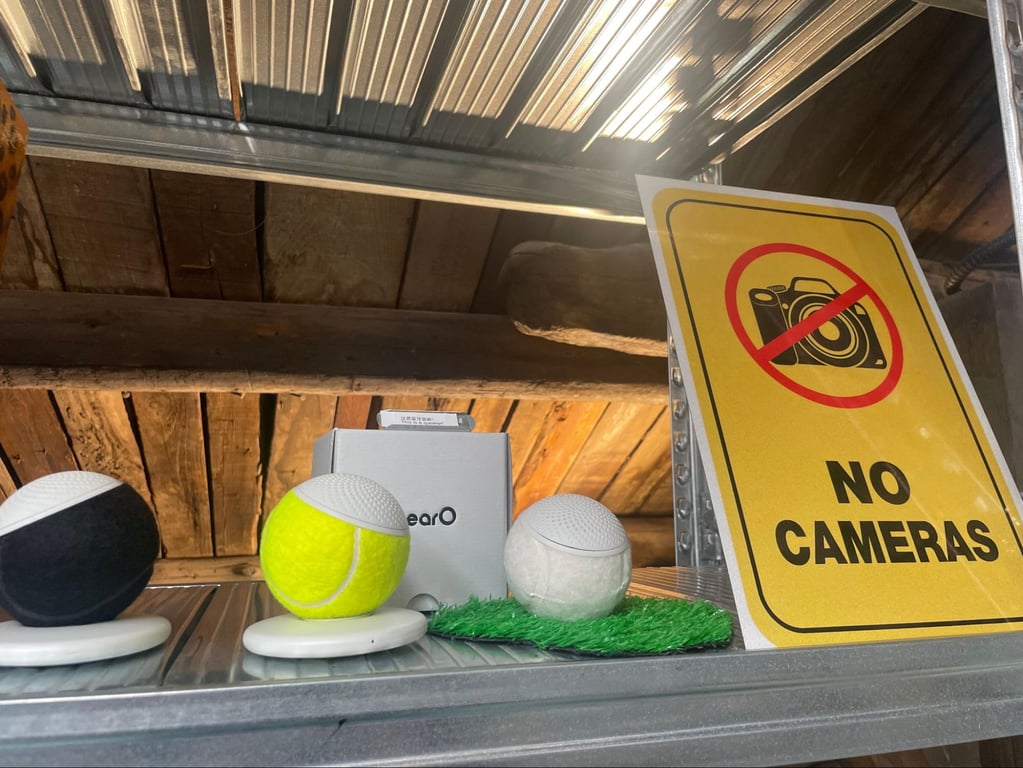

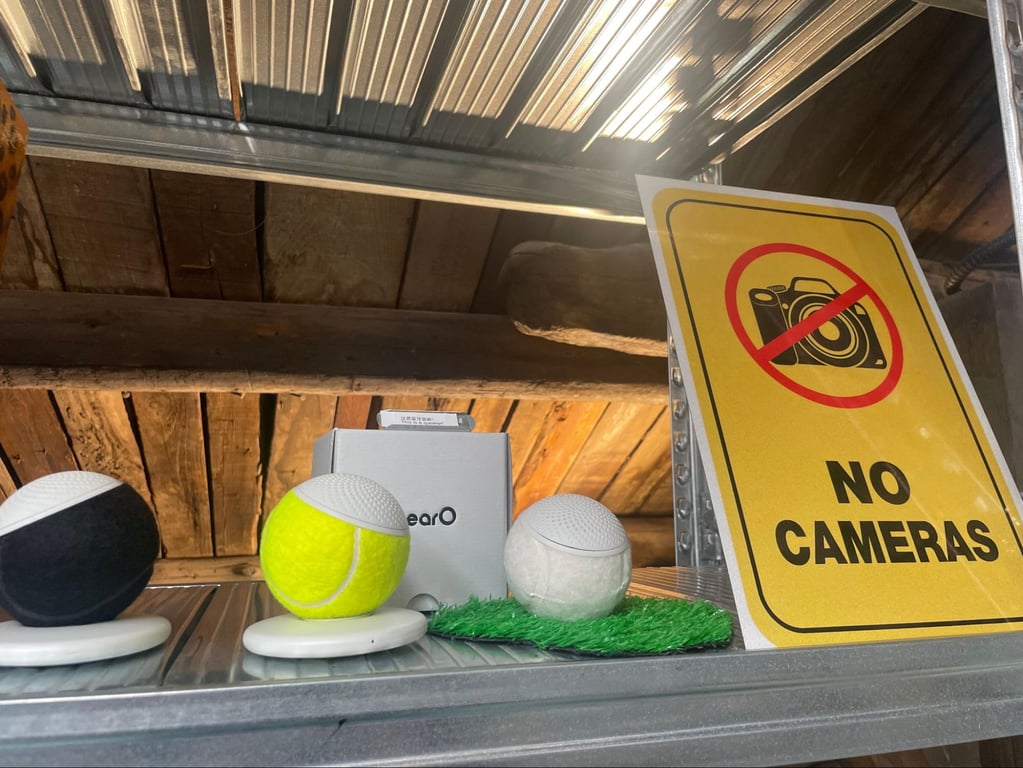

postpost Sanlitun’s bannister, esoteric jewelry, and Bluetooth speakers made out of Wimbledon match tennis balls.

Xiao Yong’s idea for a bookstore stemmed from his days studying art in graduate school, where he gained more knowledge in the library than in the classroom. Recalling how a professor drew comparisons between TV shows like The Walking Dead and Keeping Up with the Kardashians and contemporary art, he sought to recreate that chaotic mix of disciplines in the San Francisco bookstore he opened with friends. However, rising rents, driven by the tech companies based nearby, forced them out. Disillusioned with galleries’ superficial displays, Xiao Yong believes that art should be integrated into people’s everyday lives. By selling relevant books filled with thought-provoking ideas, he wants to bridge the gap between the elite and regular consumers, fostering meaningful exchange.

Semi-realistic candles made by an Italian factory with a century of history. postpost was on a long waitlist for wholesale orders.

An “open shelf” for goods from local artists and product-makers, which postpost solicits through periodic open calls.

The first postpost store opened in 2019, located in Yangrou Hutong in Xisi, a relatively ungentrified traditional neighborhood on the Western side of the city. Its clientele includes hipster art students, white-collar workers, state enterprise employees, and occasionally, monks from the nearby Guangji Temple. As customers from different demographics explored the store, Xiao Yong would adjust the music, sometimes switching to the distorted sounds of gabber, and gauge reactions. postpost evolved into an experimental playground or meta-art project, capturing the diverse responses of its patrons.

The front door and main space of the Yangrou Hutong location.

For example, three years ago, postpost put a book by Swiss artist Clément Lambelet up for sale. Investigating how AI systems struggle to decode human emotions, the publication had a digitally altered face printed on its cover. After the book arrived on postpost’s shelves, a well-known wanghong (网红, influencer) posed with the book over her head and shared the photo on social media. This sparked a sensation and lead more and more people to visit the store just to daka (打卡, pose for the same photo and share it on social media). However, this zombie-like imitation contradicted the artist’s original intent. Blindly following a social media trend, people were reduced to mere machines, easily recognizable and lacking unique characteristics.

Most other businesses in China would have either unironically embraced the unexpected popularity of Lambelet’s book, or pointedly kept silent to maintain an air of intellectual seriousness. But not postpost: the store posted photo after photo of influencers in more or less the same pose on their official WeChat account, reveling in the absurdity of performative online identity.

A collection of influencer selfies with Lambelet’s book, via postpost’s WeChat.

Ironically, the Sanlitun postpost, opened in 2023, attracted even more wanghong, much to Xiao Yong’s frustration. He even placed a sign saying “no photos after 2 pm” on the wall, but the store still filled up with wanghong, no matter how hard he tried to chase them away. This didn’t sit well with postpost’s more dedicated customers, nor people who just came to enjoy a coffee. The new arrivals didn’t understand the books or the music. Hearing Middle Eastern techno in the store, one young mother even accused them of playing music from an evil cult. “But we still want all kinds of people to come in, even if they insult us. At least it’s something different, something new. It brings a cultural shock to them in a state of increasing hegemony,” Xiao Yong explained.

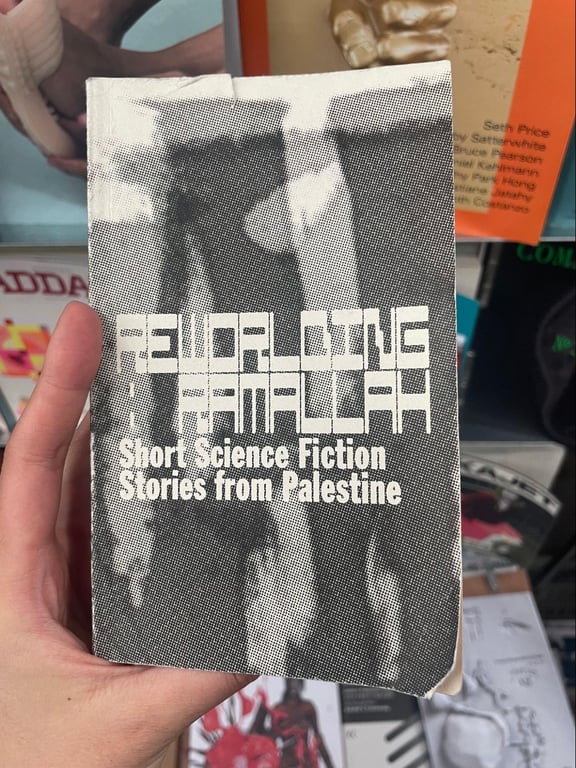

postpost prominently features magazines, literary zines, comic books, and music related to the Middle East and other Arabic-speaking areas, to, in Xiao Yong’s words, “Decrease the distance/fear factor in how we perceive that otherly culture.”

Jewelry handmade by prisoners in Turkey, and candles from artist Maggie Menghan Chen.

This rebellious spirit comes at a price. In addition to a slumping economy, independent booksellers face scrutiny in China, especially those importing foreign books. Xiao Yong has firsthand experience with the difficulties of getting books across the border. Now, he is opting to introduce more local books, which is a difficult task as postpost prides itself on how wide-ranging its selection of foreign publications is. “It will require a different curation strategy. We’ll need to spin our content angle to remain unique to our DNA.”

A bicycle seat cover made by an old Beijing leather maker out of FREITAG bag materials for a postpost project. Interestingly for Xiao Yong, the leather maker revealed he had almost gone to work in Tunisia in the 1980s.

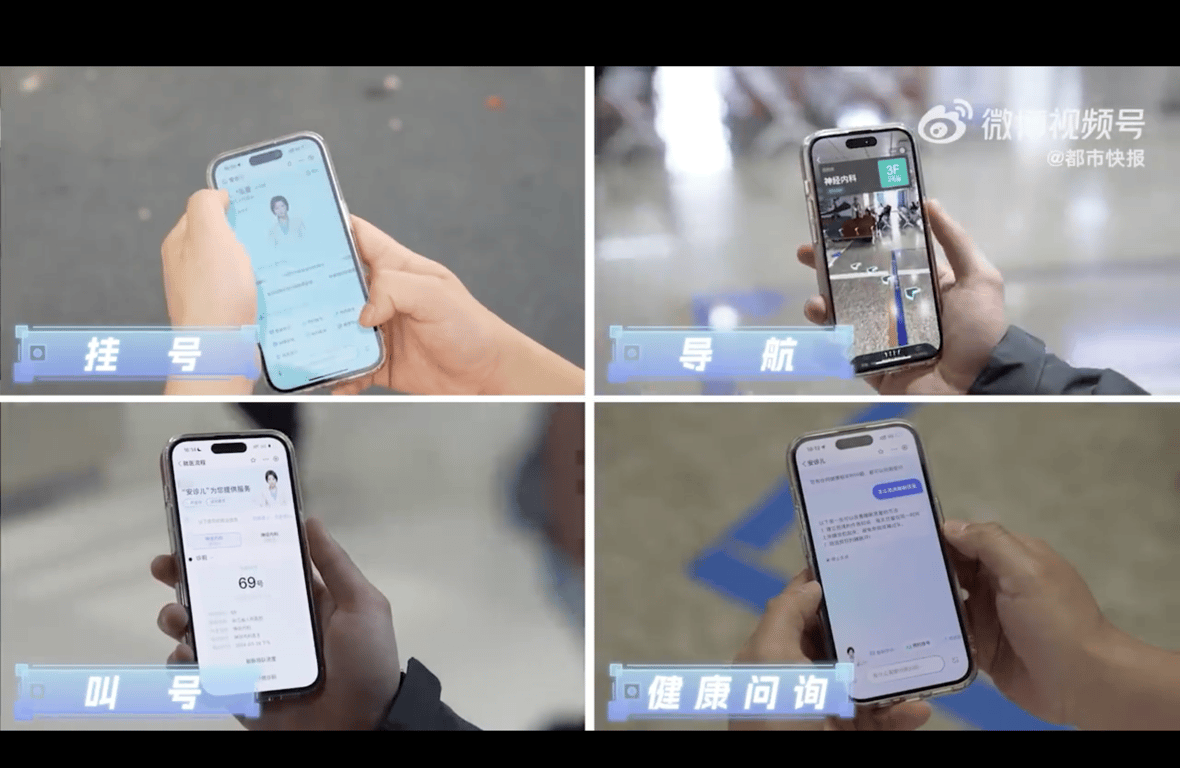

As we spoke, Xiao Yong was preparing posters for the Open M Art Fair in Chengdu. Despite his art degree, he doesn’t draw and sought help from Midjourney. He conducted an experiment, inputting words to generate pictures and then feeding those pictures as new prompts. Thus, what originally depicted a woman holding a knife in Egypt gradually transformed into a group of smiling women holding an image of a political figure in China, revealing the AI’s embedded biases.

postpost’s Yangrou Hutong location occasionally hosts events, such as this collage workshop on lucid dreaming organized by aphakia.

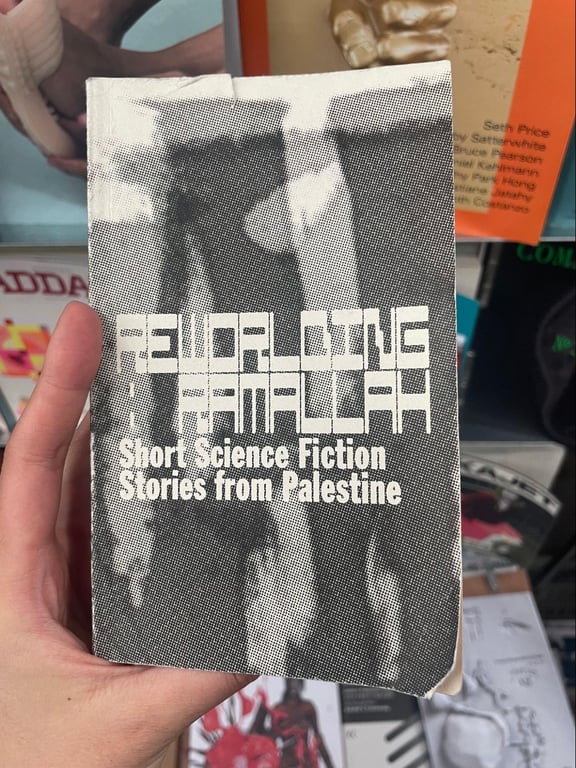

As we continued to discuss the dismantling of prejudices across nations and the increasingly blurred boundaries between humanity and technology, all while savoring sips of coffee and enjoying the accelerated beats coming from the shop’s speakers, our conversation grew more intense. “For example, it feels thrilling to read this kind of book in Beijing,” he said, referring to the collection of science fiction stories from Palestine that I happened to be holding. “But if you were to read it in a city in the South, like Guangzhou, you would feel less intensity. Yes, in Shanghai, the books would sell out within minutes, making a profit, but there’s less resistance there.”

“I often walk across [the city] to have lunch with friends on the other side of Zhongnanhai,” he continued. “The surveillance cameras track you, and if I stop, they all look at me. I feel satisfied with the attention, like a kid, and then I continue on with my walk.”

All images by Rachel Zheng unless otherwise noted.

Visit postpost at Xingfu Sancun Wuxiang, Sanlitun Jiedao, Chaoyang District, Beijing, and No. 58 Yangrou Hutong, Xicheng District Beijing.