RADII Voices is a series of short documentaries looking at the unique characters, scenes, and phenomena that define modern China.

“I want to pass what my coach taught me to my students,” says Liu Yufei, a 23-year-old former professional ice hockey player who now coaches in Wuhan. “It’s like passing down inheritance from generation to generation.”

With a team of 13 kids, Liu has essentially created the first children’s hockey team at Weiga Ice Rink in Wuhan — the Snow Wolves. She even designed their first uniform and logo. Her ultimate goal: to create an all-girls hockey team.

Though there are only four girls on her team right now, Liu says she has witnessed a growing interest in ice hockey amongst kids and parents in Wuhan.

Most kids, girls especially, come to the ice rink to learn figure skating, but some have seen her and other kids working on ice hockey drills and become interested in that instead.

Ice hockey is still a niche sport in China, and Liu notes that she often has to explain what it is to new friends. But thanks to the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, people in China are becoming more aware of winter sports, including hockey.

With Beijing winning the right to host the 2022 Winter Olympics in 2015, money and resources have poured into various winter sports activities over the last few years.

Both provincial governments and business industrialists have invested in winter sports centers across the country, including greater investment in the southern regions known for hot temperatures.

Related:

China Hits the Slopes Ahead of 2022 Beijing Winter OlympicsWhether you credit government promotion, Olympic hype, or the rising star of Chinese-American skier Eileen Gu, the fact still stands — interest in skiing is growing in ChinaArticle Jan 10, 2022

China Hits the Slopes Ahead of 2022 Beijing Winter OlympicsWhether you credit government promotion, Olympic hype, or the rising star of Chinese-American skier Eileen Gu, the fact still stands — interest in skiing is growing in ChinaArticle Jan 10, 2022

China has been a member of the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) since 1963 and had 808 registered female players as of 2020. The Chinese women’s hockey team is internationally competitive — they twice reached the semi-finals of the world championships in the 1990s and have competed in three Winter Games.

But due to various factors, including the inflow of younger, less experienced players and the retirement of veteran hockey players, the women’s team hasn’t performed well in recent competitions.

However, youth training programs are expanding in China, especially after Beijing’s successful bid for the Olympics.

A Team and a Family

Hailing from Harbin, the capital of China’s northernmost province, Heilongjiang, Liu was practically born with a competitive edge in winter sports.

She started her stick-and-puck journey by learning to roller skate, and was eventually scouted for the ice hockey team representing her elementary school.

In the beginning, she didn’t understand hockey, playing with her hockey stick as if it were a gun (something many youths who play hockey can likely relate to). Despite this lack of hockey knowledge, it all seemed new and exciting for 7-year-old Liu.

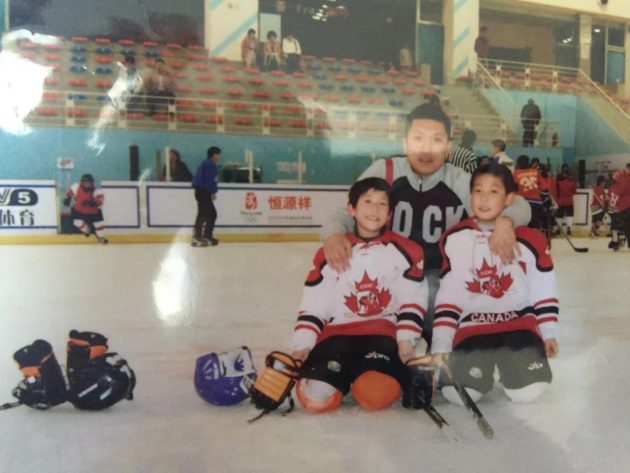

Liu Yufei (left) started to play ice hockey at 7. Image courtesy of Liu Yufei

She became serious about the sport when she saw professional players training.

“I was very envious of those older sisters who played so well,” Liu says. “So I told my dad that I wanted to play ice hockey just like them.”

After junior high, Liu went to a sports school and spent the next 10 years training and living with her teammates. Eventually, they became a family.

Liu Yufei (left) chases the puck. Image courtesy of Liu Yufei

Liu fondly recalls that they often sat around in the dorm, knitting scarves, making paper stars, gossiping about boys, and sharing secrets. They sometimes fought, too, just like birth sisters. But in the end, they always had each other’s back.

“I think that’s because women are more emotionally open,” Liu says. “We know each other so well that we sometimes communicate without saying a word.”

She adds:

“This is the most attractive part of ice hockey — we form a team, and thus become a family, because of a rubber puck.”

An Older Sister and Life Coach

Liu often went to watch whenever the national women’s team practiced in Harbin. Her eyes were fixed on the woman who wore uniform No. 55 — Qi Xueting, also known as Snow Qi.

“I always watched her play. She played so well, and she was my role model,” Liu recalls. “I even secretively took videos of her playing.”

Qi, 36, is arguably one of the most well-known Chinese female hockey players. She competed at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and will join this year’s Games as a match official.

Liu was delighted when she learned Qi would be her coach with Harbin’s top team in 2013. Qi had just retired from the national team, and Liu was one of her first students.

Qi was a tough coach, Liu says, and she often asked her students to write self-critiques when they failed in training.

“But that’s only because she thinks we can do better,” Liu says.

In 2017, Liu tried out for the professional team in Shenzhen but ultimately wasn’t selected. Many of her other undrafted teammates switched to other clubs, and some even quit the sport. But Qi encouraged her to keep going.

“If you like hockey, no matter what happens, you need to practice well,” Liu recalls Qi telling her at the time.

Two years later, Liu was drafted to the Shenzhen KRS Vanke Rays — a professional ice hockey team in the Zhenskaya Hockey League (ZhHL), which has been tasked with managing the women’s national team for the 2022 Olympics.

By joining the KRS Vanke Rays, she became a teammate with Qi, and together they won the league championship in 2020, becoming the first non-Russian team to win the cup.

Liu Yufei (left) and Qi Xueting (right) became teammates on the Shenzhen KRS Vanke Rays team. Image courtesy of Liu Yufei

Liu became a coach at the Weiga Ice Rink in Wuhan last year after retiring from KRS at the end of 2020.

However, she failed to recruit any students in the first few months. During that time, she doubted herself and often cried alone, leading her to call it quits in Wuhan and try her luck in Beijing instead.

After she finished packing, she gave Qi a call — who persuaded her to stay.

“The hockey market in Beijing is really saturated, but now you’re the first professional coach in Wuhan. You’ll certainly have more space for development there,” Liu recalls Qi saying to her. “Ice hockey is so hard, and you’ve gone through so much to get where you are. There’s no way you can’t deal with a job.”

Liu Yufei and her team of 13 kids in Wuhan. Image courtesy of Liu Yufei

Liu admits that Qi was correct — she has seen more opportunities coming to her in recent years.

She says Qi has become a life coach and a lifetime role model to her. Whenever she runs into problems, she goes to Qi for help.

“She is lowkey. She never brags but just does her best to do things well,” Liu says.

A Girl’s Team

Still, it’s not easy to recruit girls to play hockey, Liu notes, as many parents regard it as a violent sport and not suitable for girls.

“I think both boys and girls need to play ice hockey,” she says. “What kids now need most is to learn team spirit, teamwork, and sharing with others.”

Liu used to get offended when people called her a “tomboy,” but now she doesn’t care.

“Why am I not girl enough? This is just my character. I’m carefree,” she says. “You can fight really hard on the ice but still be a girl in daily life if you want.”

She adds, “Ice hockey actually suits girls better because it teaches them to be tough and not to sit back when facing obstacles.”

Liu Yufei (left) coaches a group of young hockey players. Image courtesy of Liu Yufei

Liang Lujie, 49, agrees with Liu. He’s pleased to see changes in his 10-year-old daughter Liang Yuerui. Since she began practicing hockey at the beginning of 2018, Liang says Yuerui has become stronger, more confident, disciplined, persistent, and mature.

Like many other parents, Liang initially planned to introduce Yuerui to figure skating. Instead, she fell in love with hockey as soon as she saw other kids playing it on the rink.

“She thought it’s interesting to play with the stick and fun to play with other kids,” Liang says of Yuerui’s first reaction to hockey.

Liang Lujie and his daughter Liang Yuerui. Image courtesy of Liang Lujie

Though the sport started as a hobby for Yuerui, she and her father take it more seriously today. Yuerui now practices four times during a regular week and six during holidays. Liang has also purchased full gear to practice hockey himself.

Though they’re based in the southern city of Guangzhou, Liang drove 11 hours to Wuhan last summer to hone Yuerui’s skills. She and Liu did one-on-one classes two hours a day for 15 days straight.

“Though Liu was strict and Yuerui was often crying while practicing, they bonded really well, and they both cried when we left,” Liang says.

He adds that Yuerui still asks him to video call Liu whenever she’s making progress.

“Female coaches understand girls and their bodies,” Liang says. “Liu also started practicing at a very young age, and she’s still young.”

Liang Yuerui (center) carries the puck up ice during a game. Image courtesy of Liang Lujie

Now Yuerui is the best player on her team of 12 kids in Guangzhou, and she’s one of only two girls, according to her father. She wants to join the national team in the future.

Liu tells RADII that Yuerui reminds her of herself — talented, active, hardworking, and one of the only girls on the hockey team. She hopes the 2022 Olympics will inspire more young female athletes on ice and bring her closer to her dream of an all-girls hockey team in Wuhan.

“I hope more people know the charm of ice hockey and more girls will join the sport,” she says.

Cover photo courtesy of Liu Yufei