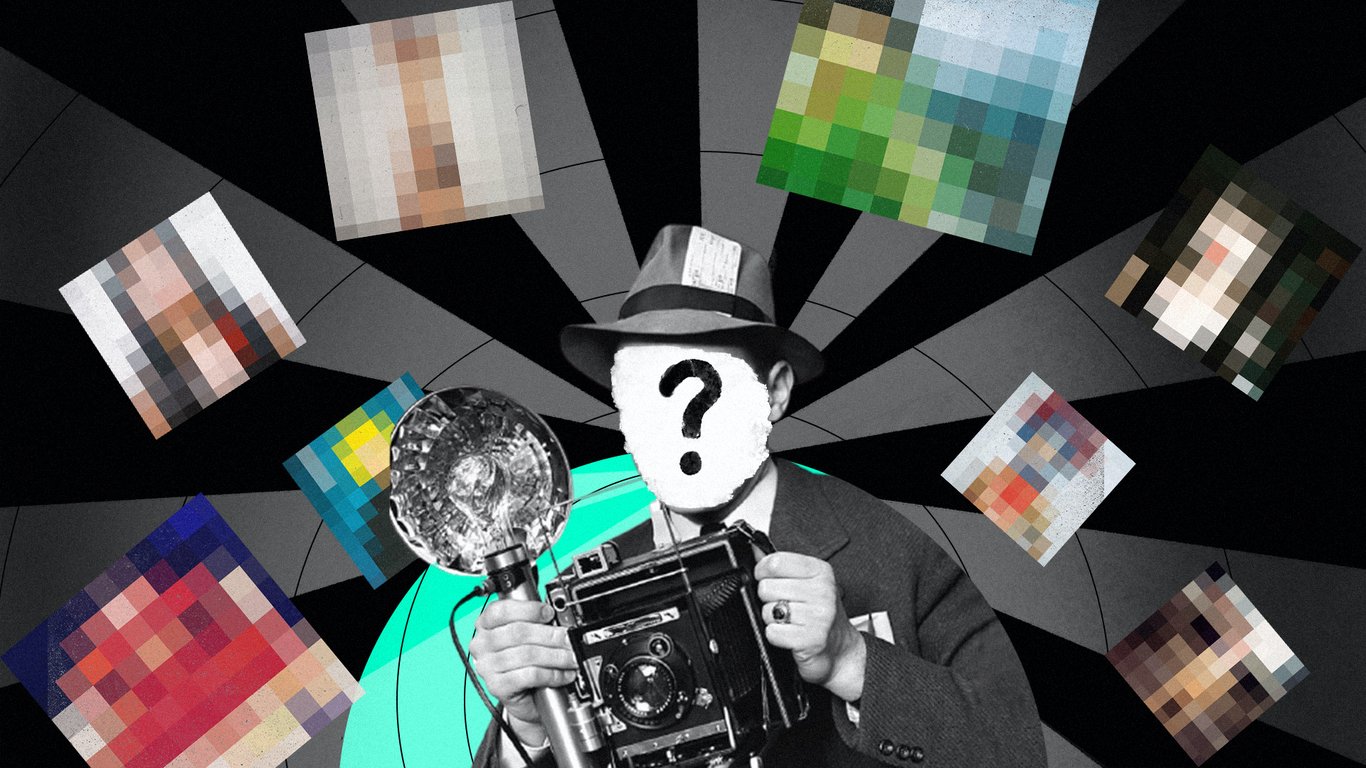

Editor’s note: In the course of researching this story, one of the authors met Lao Xie Xie for a three-hour face-to-face interview. In order to present certain aspects of this story, we felt it necessary to include his quotes, however these were given under the condition that we do not use the photographer’s real name in this piece. We have therefore used a pseudonym.

—

A pair of chopsticks pinching a naked woman’s labia; a severed pigs trotter attached to the string of a tampon inserted inside a vagina; a topless man donning a Beijing opera headdress with the words “no meaning” scrawled on his chest in red. Through his inflammatory photography, Lao Xie Xie aims to use Chinese clichés to unapologetically break new ground in the discourse on Chinese working-class artists.

Growing up in an impoverished family in Sichuan province, the photographer harbored big ideas. But it wasn’t until 2019, when he gave up his job selling steamed buns and picked up a camera, that he began to visualize them. Photography opened new worlds for the image maker and birthed his provocative style, leading to him being noticed on social media, getting multilingual press coverage and being included in international exhibitions.

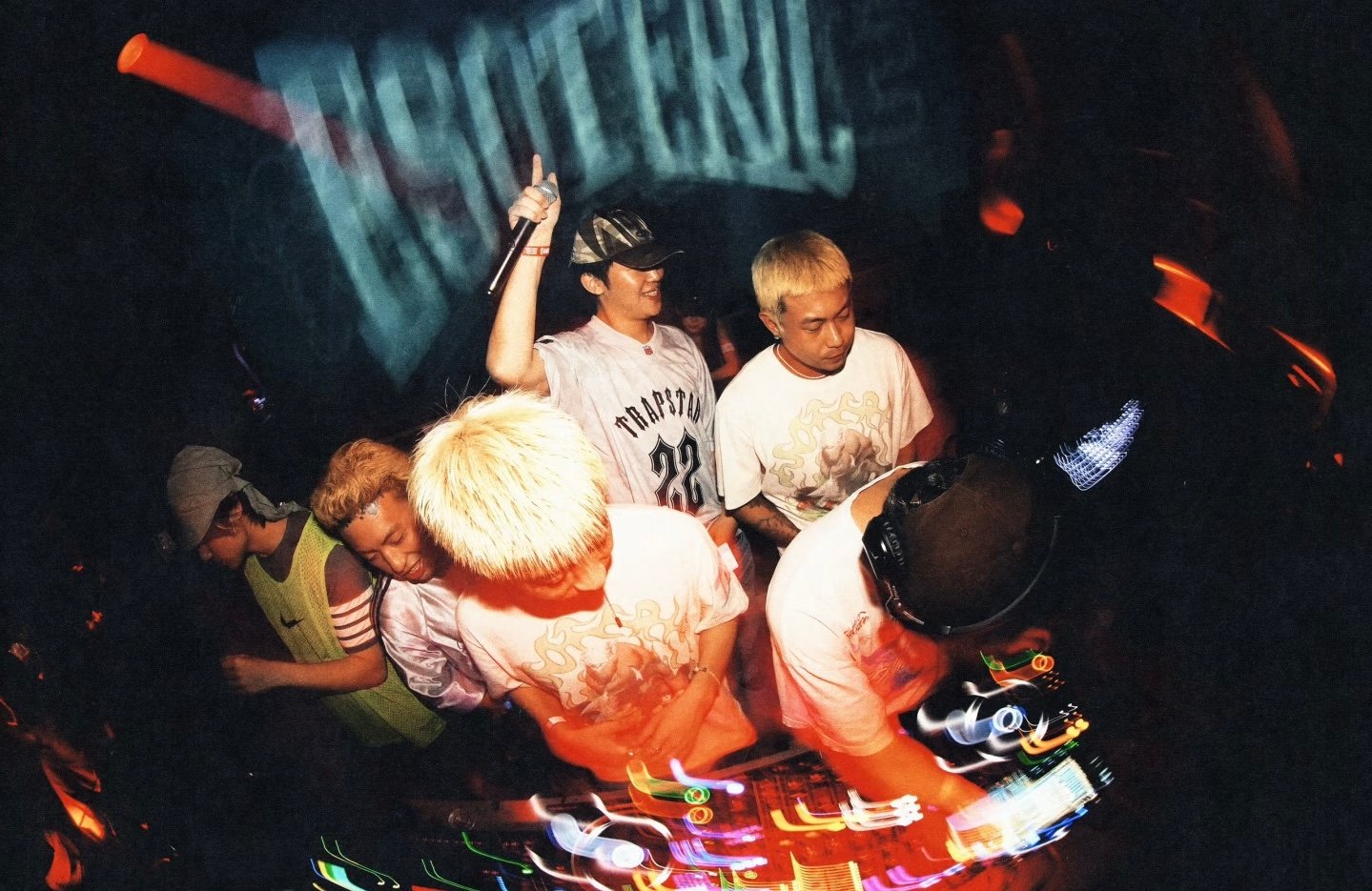

Just a matter of months after he began taking photographs, his arresting images of China’s rising subcultures have enchanted overseas audiences, landing him features in international magazines, and culminating in a Paris exhibition through September alongside works by the late photography luminary Ren Hang, among others. His rise from the backwaters of western China to the Parisian avant-garde is a triumph, not just for Lao Xie Xie himself, but for all Chinese artists.

Except Lao Xie Xie is not actually a working-class artist from Sichuan. He’s not even Chinese.

“Lao Xie Xie” (or “Mr Thank You” in English) is the fabricated identity of a white, Italian male working in the creative industries, who we will refer to as “M” in this article.

After moving to Shanghai five years ago, he turned to photography as a new mode of artistic expression. But what started as a way to showcase his creative prowess, turned into a guise that fooled media outlets into thinking he was Chinese.

We were also fooled — initially. It was only after the photographer agreed to a profile about his work that we discovered his real identity. In our first (email) interview, the artist fed into his purported Chinese identity by answering direct questions about Lao Xie Xie’s personal experience growing up in China with indirect responses about the country’s youth. Only after understanding we knew he wasn’t Chinese did he suggest meeting face-to-face. In a three-hour interview at a coffee shop in August, the open, yet highly contradictory figure, explained the genesis of Lao Xie Xie.

His inspiration to take photographs originated from a combination of frustration at creating client-centric work and a strong belief he could do better than the work displayed in the exhibitions he attended in China. While it’s not clear what being better than other people means to him, it’s clear his competitiveness drove him to pursue success.

He soon found it. Media outlets around the world were captivated by his quasi-documentary images of China’s Generation Z, images that juxtapose clichéd Chinese symbolism with explicit nudity and erotica. Unable to speak Mandarin Chinese, Lao Xie Xie mostly uses Instagram and English to recruit young Chinese Gen Zs to be his models.

By using Chinese clichés familiar to foreign audiences he aims to “to use something everybody knows to teach them something they don’t get [about China].” What exactly he hopes the audience realizes they don’t understand about China is, according to the artist, up for the audience to discern: “I don’t give you answers, I [only] give you questions.”

Maintaining his artwork is merely entertainment and doesn’t depict a real China, M contends that he feels uncomfortable that media outlets have mistakenly given him a Chinese identity. Eager to clear-up this misunderstanding, he asserts: “I didn’t pretend to be [Chinese], people think I am […] because I’m using a Chinese name”.

However, M’s role in this was not as passive as he seems keen to suggest.

When asked about the persona of the steamed-bun maker from Sichuan, he backtracks. “Ah yeah. That one in the beginning […] I asked for some tips from my friends when I started to have interviews [who said] maybe you can tell some [funny] stories,” he casually recalls of one of his first interviews. A seemingly “playful” attempt to add more meaning to his artwork was then used to foster a fabricated Chinese identity.

Although M doesn’t make a secret of his Italian identity to his models, he continues to mislead media based outside of China with a bizarre degree of ease. Using strategic equivocation, omission, and not correcting publications who report that, for example, he is female, he continues to feed into the fictitious Chinese identity of Lao Xie Xie. His goal, he candidly admits, is to make “a big buzz” because “it’s nice to play with the media.”

The media played along too. Two Shanghai-based foreign language platforms knew about M’s real identity but didn’t mention it in their reviews of his work. Two other foreign language publications mentioned in passing that he was European. There were also publications which, for reasons still unknown, reported he was female.

The ease with which Lao Xie Xie forged a believable “Chineseness” is culturally significant. In a 2015 New Yorker article discussing literary hoaxes, writer Hua Hsu explains how Asian identities are often easier to fabricate due to their perceived foreignness and that, “while other hoaxes work because of their thoroughness and care, the Asian-themed sort often get by with only a few details, as long as those details seem just ‘Asian’ enough.”

According to M, the use of a pseudonym was intended to allow him total freedom of expression while also shielding himself from potential ego-crippling criticism. Judgment from others, he explained to us, would change his own feelings towards his art if directed at him personally. Likening the persona to that of a carnival mask, M says, “it’s just egoistic. I feel freer to express my ideas in this way.”

But this wasn’t how he always painted the picture. To journalists who thought he was Chinese, he claimed the pseudonym was “for reasons regarding the safety of my life.” A fear he doubled down on in an interview with Metal Magazine, stating, “in our society, nudity is not seen as openly as in some other countries, so better be safe.” This claim of being a Chinese artist in jeopardy perpetuates and profits off two enduring stereotypes: that nudity and erotica in Chinese art is prohibited; and that Chinese artists who use nudity are political subversives.

In recent years, the increased interest in Chinese youth culture from international media has in many ways revealed a fundamental lack of understanding of China, an example being the art world’s hastiness to label Chinese artists who use nudity or erotica as “provocative,” “subversive,” or “political.” “If someone from China randomly takes a picture, the Western media will most likely extract a political metaphor from it. It’s irritating,” remarks an internationally-renowned Chinese photographer, who asked not to be named.

Related:

The Great Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll SwindleHow a postmodernist trickster convinced the world that punk rock had reached China in the early ’80sArticle May 13, 2019

The Great Chinese Rock ‘n’ Roll SwindleHow a postmodernist trickster convinced the world that punk rock had reached China in the early ’80sArticle May 13, 2019

This borderline political fetishization has seen global media frequently overlook Chinese artists who don’t fit with the “Ai Weiwei narrative” — stories of Chinese people risking censorship and jail for their artwork. “Foreign media may feel that politicizing Chinese art would make it more topical, but I always feel that they have preconceived prejudices about the Chinese political system,” says the aforementioned photographer.

While censorship towards what is perceived to be profane still exists in China, the idea that nudity is outright forbidden in the country is an anachronism. The efforts and artwork of avant-garde photographers such as Lin Zhipeng, Han Lei, Luo Yang and Ren Hang successfully pushed the boundaries and redefined society’s acceptance of sexuality and nudity, even if their work was also subject to censorship at times.

In constructing Lao Xie Xie’s backstory, M forged a Chinese identity that catfished journalists into giving him access to Chinese spaces. Publications and exhibitions with the goal of promoting Chinese or Asian artists in the international art space published Lao Xie Xie’s work thinking he was Chinese. As a result, this took away media coverage and space that would have otherwise been given to actual Chinese artists.

An example: Lao Xie Xie’s work is currently being exhibited in a Paris gallery as part of a showcase of six young Chinese photographers, and a retrospective of the late Ren Hang. Inclusion in the exhibition has increased the cost of his photographs to over 1,300USD. We reached out to the owner of the gallery and the co-curator of the exhibition, Cesar Levy, for comment. In an initial conversation over the phone, Levy appeared dismissive and didn’t seem to feel exhibiting Lao Xie Xie’s work was a major issue. He later emailed us follow-up thoughts on the matter, writing, “The idea of this exhibition was to stop with Westerner’s Chinese clichés […] we try to show the real and new faces of the countries we show here. So, I feel bad that he faked a Chinese identity.”

M feels entitled to these spaces by default of platforms believing his lie. “I didn’t push too much to hide my identity. So, they see my work, they contact me, [so] why then [should] I have to say no?”

Why, indeed?

Lao Xie Xie’s story adds another page to an already long history of white men profiting by appropriating Asian identities. Activist Brian Kern’s identity as “Kong Tsung-gan”, poet Michael Hudson’s pen name “Yi Fen Chou” and Marvel Comics’ Editor-in-Chief CB Cebulski’s persona “Akira Yoshida” are just a few prominent modern examples of the one set by French writer George Psalmanazar, who in 1704 claimed to be a Taiwanese “savage” to market his largely fabricated chronicle of the island.

Lao Xie Xie isn’t even the first such case in the Chinese art world. In 2015, Alexandre Ouiary revealed his decade-long facade as Tao Hongjing, a persona he fabricated to increase the value of his work. And in 2019, Matthiaus Austel (known as MA‘TE), sparked outrage in China’s photography scene when, prior to being accused of sexual assault by his models, he was outed for using his Chinese girlfriend’s identity to sell his work and enter into Chinese-only photography competitions.

In a time when the dialogue between China and the rest of the world is opening up on a cultural level, an ideological question thrust into the spotlight is “who has the authority to tell China’s story?” Race, culture and national identity are not monolithic ideas, and no one group lays exclusive claim to their portrayal. Yet, when non-Chinese artists appropriate a Chinese narrative for personal gain, they gamble with undermining and perpetuating historically and socially constructed prejudices and stereotypes. This issue, warns photographer Pixy Liao, runs the risk of “reinforcing stereotypes of the Western way of viewing Chinese.”

Related:

Interview: Photographer Pixy Liao On Pushing New Boundaries in Gender Non-Conformity“I accept the fact that the world surrounding me will never completely accept me,” says the Shanghai-born photographerArticle Dec 16, 2019

Interview: Photographer Pixy Liao On Pushing New Boundaries in Gender Non-Conformity“I accept the fact that the world surrounding me will never completely accept me,” says the Shanghai-born photographerArticle Dec 16, 2019

Photography’s power to challenge preconceptions and influence new narratives drew Liao to the medium. “As a Chinese woman, the reason why I make photos is because I’m tired of being portrayed in a stereotype both shaped by our own culture, history and by the Western idea,” she says.

“Photography has evolved into a language and language is a communal activity,” explains artist and photographer Tommy Kha. This communal language has the power to influence public perception of the people and cultures it portrays. While any culture observing another will view it differently, the goal, as Kha states, is not “to control interpretation,” rather it’s to increase self-awareness of “how we participate in language when we add to it.” Therefore, an essential trait of the contemporary photographer is not only awareness of one’s own positionality, but awareness of the audience’s standpoint towards the subject and cultures portrayed.

The question, then, as writer and Jezebel co-founder Anna Holmes has suggested, may not be so much about who tells a story, but rather how it’s told. In her 2016 New York Times article, Holmes argued that a commitment to understanding the many perspectives of a story is what distinguishes an artist who reveals “larger truths about ourselves and others” from one engaged in exploitative personal gain.

As Chinese artists carve out voices and spaces for themselves in the international art world, they reclaim expression of their own identities and creative languages. With space to build authentic, nuanced languages, Chinese voices have the opportunity to break through taboos and challenge prejudice.

Non-Chinese artists pretending to be Chinese not only make a mockery of the need for increased representation of misunderstood and marginalized groups, they also ideologically manipulate the authentic voices already in the room. When Western-centric gazes are passed off as authentic Chinese ones, in addition to taking away agency and space from Chinese artists, it also, as Tommy Kha asserts, “takes away authorship over experiences that influence our language.”

When asked about Lao Xie Xie’s future, M excitedly shared plans to reveal his real identity by way of “killing” his persona through posting a picture of his passport to Instagram. A public execution, he explains, to be carried out only after “I publish a book and some exhibitions to make my ego happy.”

While some may see an endearing anarchic quality to artists like Lao Xie Xie who “break the rules,” the flip side to gaming a predictable system for personal gain is perpetuating an oppressive one at the expense of progress.

And, while M prepares to “kill” his Chinese persona and reclaim his own identity with a simple Instagram post of his passport, Chinese people, says Kha, “are left to re-authenticate ourselves.”

—

Clarification: An earlier version of this article linked to a profile of Lao Xie Xie on another site and suggested that the publication had left off details of the photographer’s foreign identity from their Chinese language coverage. They have since clarified that the note about his nationality was “retroactively added in the English copy (despite objections from the photographer)” and the Chinese version was not updated in error (something they’re now rectifying). We have therefore removed this line in the article above.