Photosensitive is a monthly RADII column that focuses on Chinese photographers who are documenting modern trends, the youth and society in China.

Coca Dai is snap-happy. While we sit and chat with the photographer beneath a sun-beaten parasol in Shanghai, he has his camera in position, picking it up every so often to snap an image.

Against the backdrop of the near-continuous sound of his camera shutter, Dai talks us through his career to date, one that has seen him win international acclaim despite never formally studying photography. Yet it’s perhaps his constant surveying of the scenes playing out around us that is the most revealing aspect of our time with him: Dai’s body of work is characterized throughout by an authenticity and intimacy, whether his lens is trained on his own wife or on strangers on the subway wearing face masks.

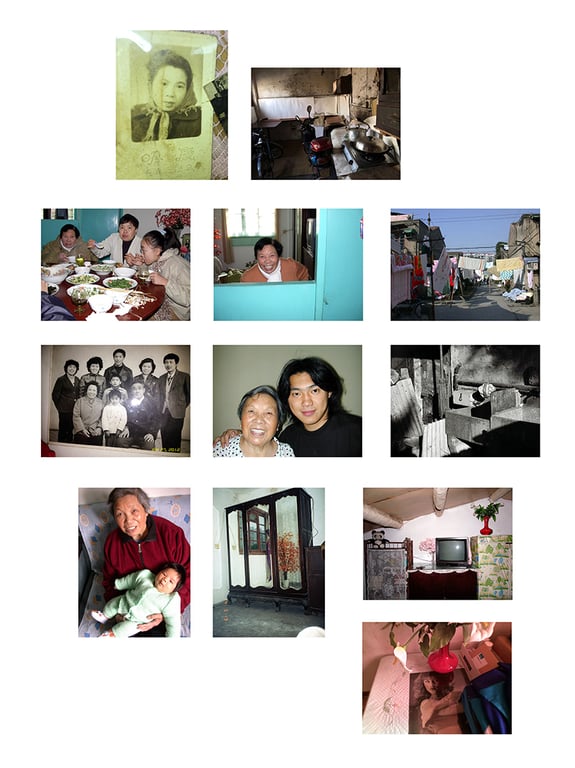

One of his best-known collections is Three Decades: A Family, a chronicle of the life and pain of his family over the course of 30 years via three generations. The collection is centered around ideas of disconnection and division, reflecting on his relationship with his Shanghai family during his early years. As you pass through the decades in the collection, the tone gradually softens as it moves into Dai’s married life.

Three Decades shows the fortunes of a family in modern China, consisting of numerous turbulent scenes. We see fights with Dai’s cousin over housing benefits, images of crumbling apartments prepared for demolition and his grandma’s final moments. Each photo is intuitive, imposing and powerful, silently telling unvarnished personal stories against the looming background of a rapidly changing China.

Another key thread throughout the series is Dai’s own search for identity. At the age of 17, Dai moved to Shanghai from rural Wuyuan in Jiangxi province, a change he sees as a watershed moment in his life and one that prompted him to eventually pick up a camera. Thanks to a national hukou (household registration) policy at that time, Coca was able to take up residence in the city, yet in some ways struggled to find his place in it.

Related:

Interview: Photographer Luo Yang is the Queen of China’s Beautiful YouthThe photographer has made her mark on modern culture by documenting the many faces of China’s youthArticle May 07, 2020

Interview: Photographer Luo Yang is the Queen of China’s Beautiful YouthThe photographer has made her mark on modern culture by documenting the many faces of China’s youthArticle May 07, 2020

“I will never become a true Shanghainese, just like my mom will never become a true Wuyuanese after she moved to Wuyuan,” he says. This lack of belonging manifests in photos of Shanghai juxtaposed in his collection with shots of his old home in Wuyuan.

Similar themes are tackled in another of Dai’s series, which is just as up close and personal: Judy Zhu 2008-2015. While his previous collection focused around familial matters related to his early adulthood, this collection is very much about the intimacy between him and his wife Judy Zhu. For this series, Zhu was photographed candidly in every possible way — falling asleep while feeding their kids, resting on the sofa, or brushing her teeth. The immediacy and honesty of the pictures is absorbing.

The idea to make a book out of the series came later. One day, while revisiting the 50,000-odd photos in the series, Zhu burst into tears. While the photos in the series can seem somewhat scattered and aimless, together they are a legacy of the pair’s young love.

Dai’s publishing of the photos led to his work being displayed at two of China’s biggest art events: the Shanghai Biennale (in 2016) and Jimei x Arles International Photo Festival (in 2018).

Related:

Photographer Lnshiy On Her Mission to Subvert Beauty Standards and Elevate WomenLin Shiyang’s photography examines what it means to be a woman in an age obsessed with a concept of beauty that oppresses more than empowersArticle Sep 23, 2019

Photographer Lnshiy On Her Mission to Subvert Beauty Standards and Elevate WomenLin Shiyang’s photography examines what it means to be a woman in an age obsessed with a concept of beauty that oppresses more than empowersArticle Sep 23, 2019

More recently, Dai has become infatuated with capturing the honesty of nude models. “One of the greatest powers we are born with resides in our body, but we have ignored it, as we are busy being creative with clothes,” he says. “The beauty of our bodies is worth awakening.”

The models that he has captured are all strangers with whom he connected on social media or through friends, he explains. “Nothing is intentional, the set-up, the pose, the facial expressions. I just ask them to be themselves. We could have conversations, but we do not have to. They are at ease and are in a natural state in front of me.”

In this way he is able to access images that are almost wholly authentic. “When everybody is hiding behind the curtain of social media accounts with filtered photos, nude photography is liberating in a sense that it provides people with a chance to stay true to themselves,” he says. “Even if my photos are not necessarily artistic for some people, they are authentic.”

Related:

Interview: Photographer Pixy Liao On Pushing New Boundaries in Gender Non-Conformity“I accept the fact that the world surrounding me will never completely accept me,” says the Shanghai-born photographerArticle Dec 16, 2019

Interview: Photographer Pixy Liao On Pushing New Boundaries in Gender Non-Conformity“I accept the fact that the world surrounding me will never completely accept me,” says the Shanghai-born photographerArticle Dec 16, 2019

Cameras tend to see the outside world without compassion, but Dai uses his camera to bear the weight of the love he has for his family, as well as for ordinary people — who are also important participants in his daily life.

His ongoing street photography project 100K Humans Who Look at Their Phones attempts to examine the relationships between people and technology. “Phones are like prosthetic limbs to people as they are excessively dependent on them,” he says.

Also within the intersection of the urbane and humane, Dai’s latest project — Humans Who Wear Masks, reflects on the impact that the Covid-19 pandemic has had on humanity. Amidst the outbreak, donning a mask became a regular part of everyday life for people all over China. This phenomenon has posed an open-ended question to all of us: How have masks, or Covid-19 in general, changed interpersonal relationships and the way we think, behave and live?

This is just one of the many questions Coca is hoping to answer with his camera.

As he once revealed, one of the main reasons he takes photos is to battle against a deep insecurity in his mind: he uses photography to capture love and connection, to hold on the present and to keep himself from forgetting these bonds and the moments that make them. To that end, he’ll continue to be snap-happy. As his intuitive photographing style suggests, he believes, “the best way to become a photographer is to take more photos and to find your own style.”