[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Rokuon-ji, better known as Kinkakuji or “Temple of the Golden Pavilion,” is one of the most famous sites in Kyoto. The gilded pagoda draws crowds from all over the world. On the day I’m there, it seems that most of the visitors are from mainland China. Buses disgorge large groups of eager Mandarin-speaking tourists who crowd into the temple’s garden for selfies and family photos. The site (if not the building, more on that later) dates back to the 14th century, although one young visitor seems less than impressed by the history, screaming “bu yao!” “bu yao!” “bu yao!” (“don’t want”) as his parents/handlers try to get him to pose standing in a pile of recently fallen red maple leaves.

Walk down a street, any street, in the center of Kyoto and within a few blocks you’ll be standing outside a temple or shrine. Kyoto has some of the best-preserved historic architecture in Japan, and some of the credit for this may be due to one of China’s most famous architects and preservationists: Liang Sicheng (1901-1972).

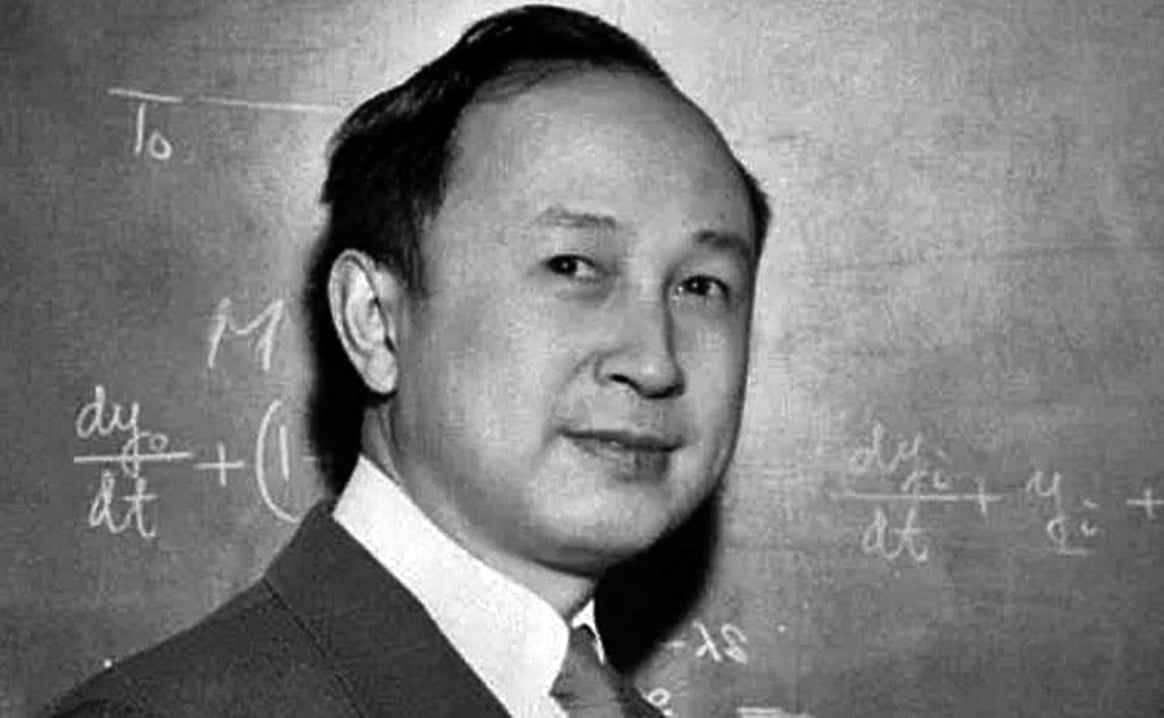

The son of the influential reformer and writer Liang Qichao (1873-1929), Liang Sicheng was born in Japan during his father’s exile following the failure of the 100 Days Reforms in 1898. The younger Liang graduated from Tsinghua College (later Tsinghua University) in 1915 and, along with his future wife Lin Huiyin (1901-1955), studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

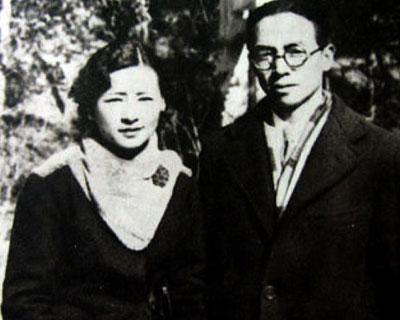

Architecture power couple: Lin Huiyin and Liang Sicheng

Over the next two decades, Lin and Liang became an architectural power couple. The pair discovered some of the oldest remaining wooden structures in China among the Buddhist temples at Wutaishan. Liang and Lin also founded architecture departments at universities throughout China and Liang later represented China on the board which designed the UN headquarters in New York.

For their home, the couple restored an old courtyard on Beizongbu Hutong in Beijing which soon became an intellectual center and a salon. Amidst the halls and courtyards of their siheyuan (the Chinese term for courtyard), Liang and Lin entertained academics and artists, poets and politicians from around the world. (Don’t bother to look for the courtyard today, sadly it was demolished by a State-owned real estate development company in 2012).

During World War II, as Japan occupied Beijing and most of coastal China, Liang Sicheng was working in Sichuan. According to Luo Zhewen, a former student who frequently assisted Liang Sicheng in his research, Liang heard that the Allied forces were planning on bombing Japan and Japanese-controlled areas in China. Liang began drawing up a map of the major Chinese cities occupied by Japan as well as Japan’s former capitals, Nara and Kyoto to help American military planners avoid destroying important historic sites and buildings. Liang then traveled to Chongqing, the wartime capital of the Republic of China, and passed the maps to the US Army liaison stationed there.

Whether the US Army followed Liang’s recommendations is a bit unclear. Kyoto was ultimately spared the worst of the allied bombing campaigns and Henry L. Stimson decided to replace Kyoto with Nagasaki as the target for the second atomic bomb. The US Secretary of War may have had an affinity for the city which influenced his decision. There is also evidence that Langdon Warner, a Harvard professor and expert on Asian art, appealed to Stimson to protect Kyoto and other historically significant sites in Japan.

Liang’s student Luo, as well as two other later associates, claim that Liang played a role in preventing the destruction of Nara and Kyoto. Given Liang’s stature at the time as one of the leading experts in Asia – if not the world – on historic preservation it is indeed plausible that his recommendations would have been taken seriously.

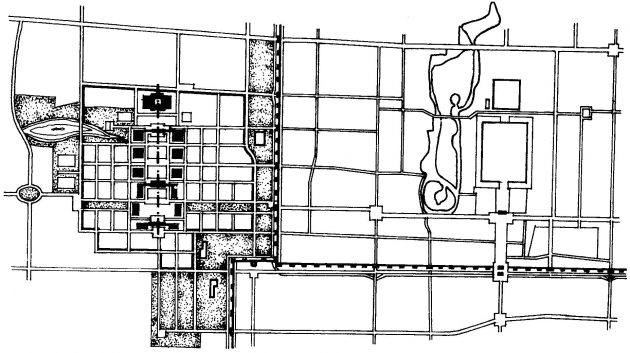

And if Liang did play a role in protecting the cities of Japan, then it’s hard not to see a bitter irony in the fate of his adopted home city of Beijing. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the new government asked Liang Sicheng to assist in the redesign of Beijing as the recently-restored national capital. Along with fellow architect Chen Zhangxiang (1916-2001), Liang submitted a proposal to preserve the famous city walls and the neighborhoods within while constructing a modern administrative capital to the west of the old city.

A plan by Liang Sicheng and Chen Zhanxiang to build a new administrative capital to the west of the city walls while preserving much of the historic city center.

Chairman Mao was not impressed with Liang’s recommendations. Mao wished to transform Beijing into a “city of production” with smokestacks as far as the eye could see. Mao was also probably grooving on his new digs in the former imperial gardens at Zhongnanhai. The government rejected Liang and Chen’s plan and the walls came down. Today, successive waves of poorly planned development have led to the destruction of much of Beijing’s historic architectural legacy.

Back in Kyoto, the Golden Pavilion continues to draw Chinese tourists. One local guide wondered if it was because the gaudy tower was more in “keeping with Chinese aesthetics” as opposed to the earth tones favored by other temples in the city. Or there may be another reason. “The Chinese love new things,” the guide declared. “The Golden Pavilion you see here isn’t that old. The original survived centuries of conflict. It even survived the American bombs. But in the 1950s a crazy monk burned it down. What you see here is only a few decades old.”

As Liang Sicheng once wrote, “architecture is the epitome of society and the symbol of the people. But it does not belong to one people, for it is the crystallization of the entire human race… once destroyed, it is irrecoverable.”

You might also like:

It’s Not Rocket Science, Except When it is: The Strange Case of Qian XuesenArticle Aug 15, 2018

It’s Not Rocket Science, Except When it is: The Strange Case of Qian XuesenArticle Aug 15, 2018

Quadruple Drawing of a “Dirty Street” in Beijing Wins International Architecture PrizeArticle Oct 18, 2018

Quadruple Drawing of a “Dirty Street” in Beijing Wins International Architecture PrizeArticle Oct 18, 2018