In the pantheon of batshit inanities to issue forth from the mouth and stubby fingers of one Donald J. Trump, the President’s offhand comment earlier this month insinuating that almost all Chinese students in the US are spies barely registered.

The president’s remark, given during a dinner for CEOs at President Trump’s private golf course, comes amidst an escalating trade war, concerns over Chinese theft of intellectual property, and growing unease about the extent to which the Chinese government, military, and the Chinese Communist Party through its United Front agency are expanding their influence and operations within the United States. New regulations enacted in June limit Chinese graduate students in specific high-tech fields to one-year renewable visas, a departure from Obama-era policies which allowed Chinese students to apply for five-year visas.

But targeting members of a specific community and efforts by the US government to impose restrictions on visas and subject Chinese researchers to additional scrutiny can also backfire. Consider the case of Qian Xuesen.

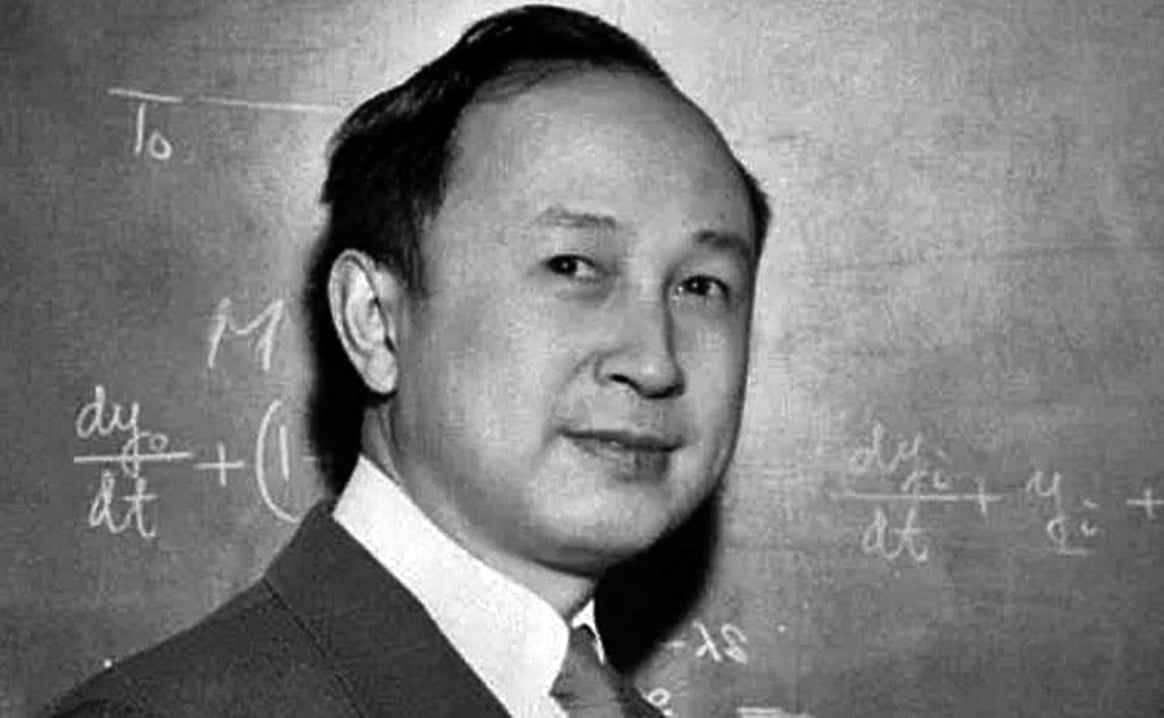

Qian Xuesen was one of the best and brightest rocket scientists in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s but was forced to return to China during the Red Scare of the 1950s. Qian spent the rest of his career in the PRC and provided a critical boost to China’s efforts to modernize their military rocketry and space programs. Here, he is celebrated as a hero of the nation and Qian’s research led to the production of China’s first ballistic missiles, its first satellite launch, and the development of the Silkworm anti-ship missile.

The Qian Xuesen Library beside Shanghai Jiaotong University

The son of a government official, Qian Xuesen was born in Hangzhou in 1911. He earned a mechanical engineering degree from Shanghai Jiaotong University in 1934 and at the age of 23 traveled to the United States on a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship, studying first at MIT and then at Caltech under Theodore von Kármán, who called Qian “an undisputed genius.”

First as a graduate student and then after earning his doctorate from Caltech in 1939, Qian played a critical role in early efforts of the United States to develop rocket and jet propulsion technology. During World War II, Qian assisted on the Manhattan Project while his other research focused on countering German rockets by analyzing the V-2 rocket program.

Qian’s work would eventually play a vital role in the development of ICBM technology and the rockets NASA would use for space exploration. In 1949, Qian wrote a proposal for a “winged space plane” that was one of the inspirations for NASA’s space shuttle. As a result of his research, in 1949 Qian as named the first director of the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Jet Propulsion Centre at Caltech.

A bust of Qian inside the library bearing his name

Unfortunately, Qian’s career at the Jet Propulsion Lab collided with political developments in China and in the United States. The founding of the PRC in 1949 and the start of the Cold War ushered in a new era of fear and paranoia in the United States.

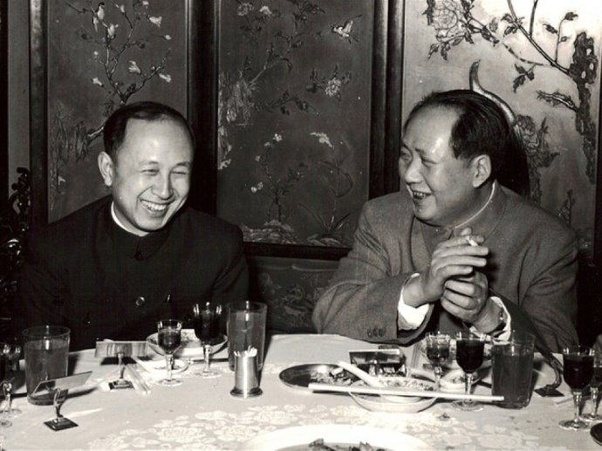

In 1950, Qian applied for permission to visit his parents in China. An FBI investigation accused him of having Communist sympathies — as a grad student he had attended a social gathering the Bureau suspected of being a Communist Party meeting — and Qian was stripped of his security clearance. Qian denied the charges, but despite the best effort of his colleagues and supporters in the scientific community, he remained under house arrest until 1955 when he was finally permitted to leave for China.

“I do not plan to come back,” Qian bitterly told a reporter as he prepared to leave the country. “I have no reason to come back…. I plan to do my best to help the Chinese people build up the nation to where they can live with dignity and happiness.”

Former Navy Secretary Dan Kimball called the decision, “The stupidest thing this country ever did.”

Upon his return to China, Qian founded the Institute of Mechanics in Beijing and became a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. In 1964, China tested its own atomic bomb. Under Qian’s direction, Chinese researchers developed the first generation of “Long March” missiles and in 1970 supervised the launch of Chia’s first satellite.

Qian Xuesen and Chairman Mao following Qian’s return to China in 1955

Qian Xuesen retired in 1991 and lived a quiet life in Beijing with his wife who was an accomplished opera singer. In 2001, Caltech awarded him its distinguished alumni award, but Qian never returned to the United States. Qian Xuesen died in Beijing in 2009.

Qian’s story is a cautionary tale. While the United States does face real and important threats to its national security from China and other countries, targeting a particular group based on ethnicity or national origin can have unintended effects with long-term consequences. It can also, as happened to Qian Xuesen, have the potential to destroy people’s lives and careers.

[pull_quote id=1]

In 2015, the Justice Department cleared Sherry Chen of espionage charges. The Chinese-American hydrologist formerly worked at the National Weather Service but was accused of using downloading information about dams in the United States and lying about a meeting with a Chinese official. Despite her exoneration, Ms. Chen still has not been able to return to work. Last year, Xi Xiaoxing, a physics professor at Temple University, filed suit after the Justice Department accused him of being a Chinese spy only to reverse their decision later. According to the lawsuit, Xi believes that he was targeted solely because of his ethnicity.

It’s hard to imagine the humiliation and crushing sense of betrayal Qian Xuesen felt due to his treatment by the United States government or the anger at having your career snatched away due to accusations and suspicions based on little more than your national origin or ethnicity. There are more than 350,000 students attending university in the United States. In 2016, students from China earned about 10% of all doctorates awarded by US institutions. There is a clear and present threat in the efforts of the Chinese Communist Party to extend its reach into the United States. — there’s no denying that — but defending American institutions should not come at the cost of American values.

—

Shanghai photos by Thanakrit Gu for RADII.

You might also like:

Commentary: It Hasn’t Always Been This WayArticle Jul 12, 2018

Commentary: It Hasn’t Always Been This WayArticle Jul 12, 2018

The National FetishArticle Jul 05, 2018

The National FetishArticle Jul 05, 2018

American Business and Chinese Nationalism: Lessons from 1905Article Apr 16, 2018

American Business and Chinese Nationalism: Lessons from 1905Article Apr 16, 2018