As more Chinese art and artists go abroad, they provoke a variety of responses — some inspiring and innovative, others reflecting stark cultural differences.

Let’s start with a positive one. London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (aka the V&A, the world’s largest decorative arts and design museum) has recently added WeChat to its collection. All of it. Kinda.

WeChat stickers at the V&A

Lead curator Brendan Cormier explains why and how the institution decided to integrate such an amorphous digital platform into the V&A’s collection in a lengthy blog post, which includes the usual “holy sh*t this really is an app for everything” boilerplate and then moves on into the meat of how exactly a brick-and-mortar museum can “collect” WeChat:

To frame things in the simplest way, we asked [WeChat’s Guangzhou-based design team] to think about the distant future. When we talk about WeChat one hundred years from now, how will we be able to show people what it is? This proved to be powerful way of thinking, because suddenly the acquisition became focused on the question of preservation, and preserving the legacy of what these designers were doing. It wasn’t simply about a museum taking something, but how we address the larger issue of digital preservation.

This is a pretty fascinating topic — applying an art historian’s mindset to an app that is so pervasive in Chinese life today that we can’t imagine what it was like before we had WeChat (about six years ago), and we’re certainly not thinking about what will come next, even though the life cycles of these technologies seem to be getting increasingly shorter.

Highly recommend you read the full post here. Otherwise, here’s a fun video the V&A made about this project:

Ai Weiwei Protested in Manhattan

Across the pond, global art star Ai Weiwei is pissing off residents of Lower Manhattan with his proposal for a sculpture that would block traffic flow through the monumental Washington Arch. The piece is part of a citywide sculpture series by Ai celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Public Art Fund.

If all goes according to plan, Ai’s piece, entitled Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, will comprise a network of fences at different locations across the boroughs, and will serve as “a reminder to all New Yorkers that although barriers may attempt to divide us, we must unite to make a meaningful impact in the larger community,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Some residents, however, worry that Ai’s Washington Arch fence will mostly just function as a literal barrier. According to the Washington Square Park Blog:

The Washington Square Association, a neighborhood organization around since 1906, issued a letter asking the Public Art Fund, the organization sponsoring the project, to “withdraw its plans” and spoke out against the Weiwei installation under the Arch.

For one, they state, it interferes with the annual Christmas tree lighting under the Arch, which their group has presented since 1924, something surely the Parks Department was aware of. They also mention that there was no community involvement in the decision as to whether this project should go forward.

Nevertheless, a Community Board with the final say on the matter voted Yes to Ai’s proposal last Tuesday, and the fence will go up, displacing the Christmas tree and teaching residents a lesson about both cultural barriers and municipal bureaucracy.

Censorship at the Guggenheim

More drama Uptown: two days ago, Chinese artists Sun Yuan, Peng Yu, Huang Yong Ping, and Xu Bing had their works removed from the Guggenheim’s landmark exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, which is scheduled to open on October 6.

Two of the works were videos — Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other depicting pit-bulls on treadmills from a previous installation in Beijing, and Xu Bing’s A Case Study of Transference, which shows live pigs fucking.

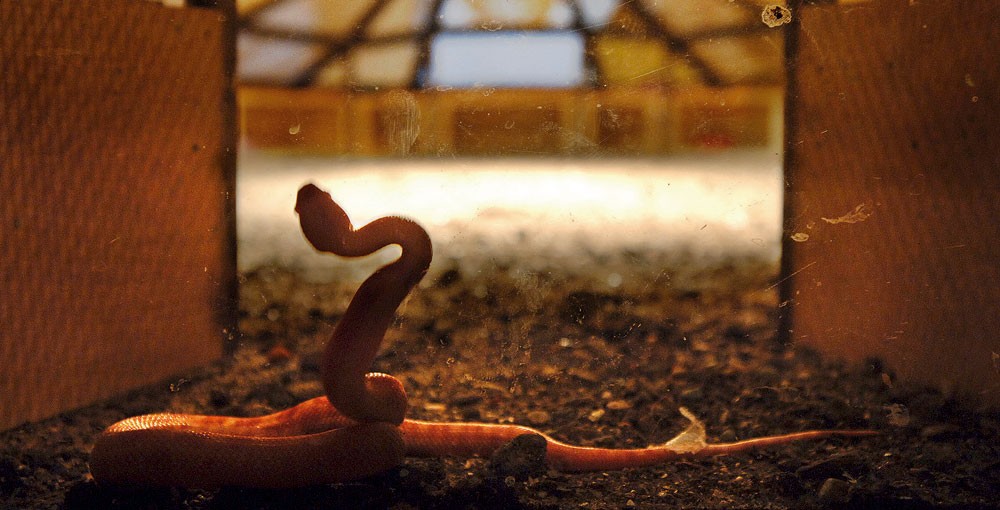

The third was the show’s eponymous centerpiece, Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World (above), which consists of a large terrarium filled with lizards and insects.

NPR reports:

An online petition demanding the museum remove the works garnered more than 600,000 signatures since it was posted five days ago, contending that three of them depict animal cruelty. The pressure mounted from there: Tweets show protesters gathered outside the museum on Saturday, holding signs that say “suffering animals is not art.”

@Guggenheim #GuggenheimTortureIsNotArt #protest happening now pic.twitter.com/8nMCze2te4

— Roxanne Delgado (@delgadoroxanne8) September 23, 2017

The Guggenheim capitulated to the protests, but released a short statement in self-defense, saying:

Although these works have been exhibited in museums in Asia, Europe, and the United States, the Guggenheim regrets that explicit and repeated threats of violence have made our decision necessary. As an arts institution committed to presenting a multiplicity of voices, we are dismayed that we must withhold works of art. Freedom of expression has always been and will remain a paramount value of the Guggenheim.

But withhold they did, in yet another episode testing the limits of free expression in America today. “When an art institution cannot exercise its right for freedom of speech, that is tragic for a modern society,” Ai Weiwei told the New York Times yesterday in response to the incident. “Pressuring museums to pull down artwork shows a narrow understanding about not only animal rights but also human rights.”

What do you think?

Is this a win for animal rights activists or an “L” for freedom of expression?

Is Ai Weiwei building a fence that will draw attention to the blockages dividing contemporary society, or is he just building a fence?

Do you have a museum-worthy WeChat sticker collection on your hands?

Hit us in the comments.

Cover image: Detail of Huang Yong Ping’s Theater of the World (via KUNSTFORUM)