What would you depict if you only had one canvas with which to capture the essence of your city?

For some, the obvious answer might be to capture facsimiles of a city’s iconic buildings. Take Shanghai’s somewhat cartoonish Oriental Pearl Tower, for instance, or Beijing’s Citic Tower, designed to resemble a ceremonial wine vessel.

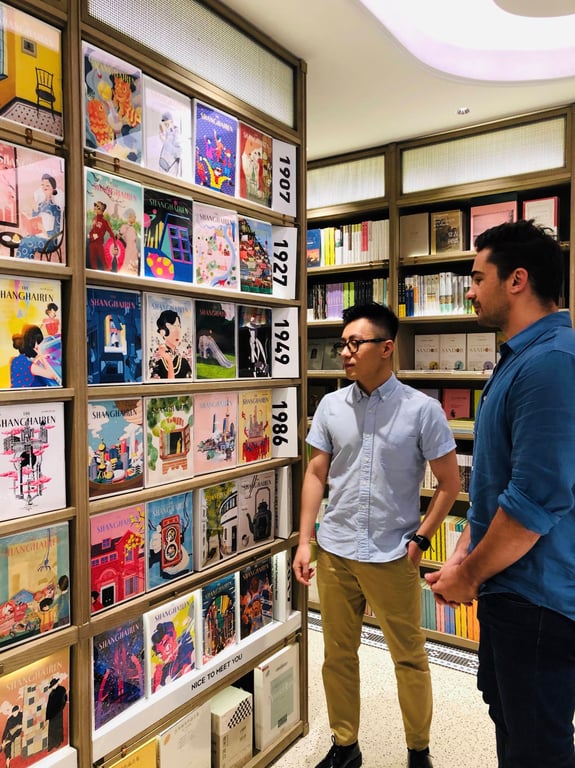

While these behemoth buildings appear between the covers of artbooks The Shanghairen and The Beijingren, several Millennial contributors chose to bring the viewer’s attention to street level.

For full-time freelance illustrator Peter Zhao, the trick to capturing a city’s soul is “walking into the streets […] and observing the local people.” The artist’s depiction of hungry customers milling about street food vendors after dusk offers “a gentler version of Shanghai, one that’s on the other side of the hustle and bustle of the city.”

Likewise, Chilean architect, photographer, and illustrator Sebastian Correa was less preoccupied with skyscrapers and more interested in the citizens that make a city.

“A real part of [the citizens] are the migrant workers doing hard work — they are the real force that moves Shanghai. So I wanted to pay tribute to the real ‘Shanghairen,’ the ones who, with hard work, keep helping Shanghai to move forward,” says the artist, hence his all-too-accurate rendition of a delivery driver sneaking in a quick nap on his scooter in between assignments.

According to both Correa and Zhou, stepping into the shoes of a flaneur also helps produce accurate depictions of a place.

“Going on long walks at a slow pace or meandering without a certain destination allows me to discover the real side of the city,” says Correa. “Observation and sketching on site are great tools to capture the essence of the place, but also to communicate and learn about certain cultures, people, and behaviors.”

“If it’s possible, I would stay and live in the city for a while,” offers Zhou.

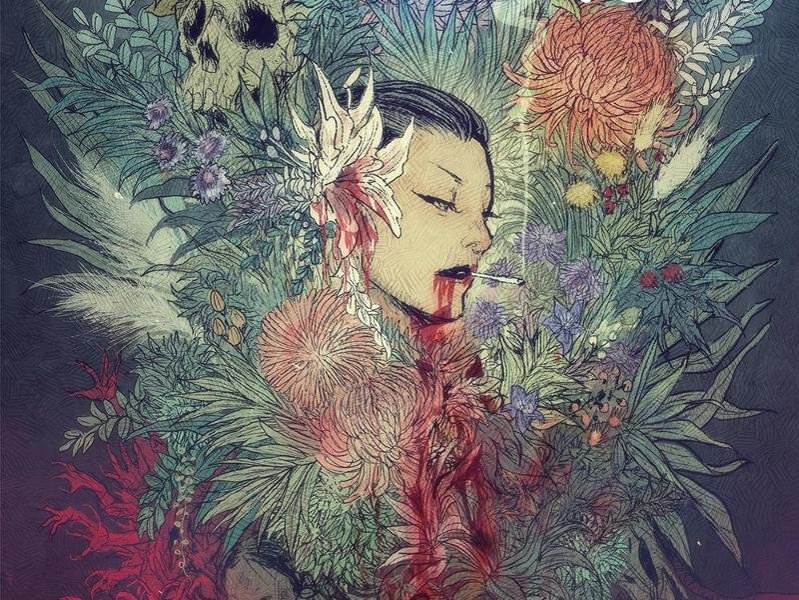

When asked to create a homage to Beijing, a city she called home for eight long years, graphic designer, curator, and freelance illustrator Wai Kwok Choi also allowed her fascination for human stories to guide her hand. But unlike Zhao and Correa, who based their artwork on personal observations, she tapped into the power of imagination.

After hearing a fascinating tale about the Fahai Temple on the outskirts of Beijing in an art class, Choi delved into further research.

In 1933, a German photographer named Hedda Morrison discovered the temple’s famed frescoes from the Ming Dynasty. In an attempt to document them while also preserving their integrity, she and a fellow photographer experimented with a DIY form of lighting — involving chemicals such as magnesium powder and paraldehyde — in the dark room. Things went awry, and Morrison ended up with burns, but her photographs exist as some of the earliest forms of documentation of the murals.

“As I viewed and created this painting, I imagined how the photographer felt back then. So I repeated and created this little story,” shares Choi.

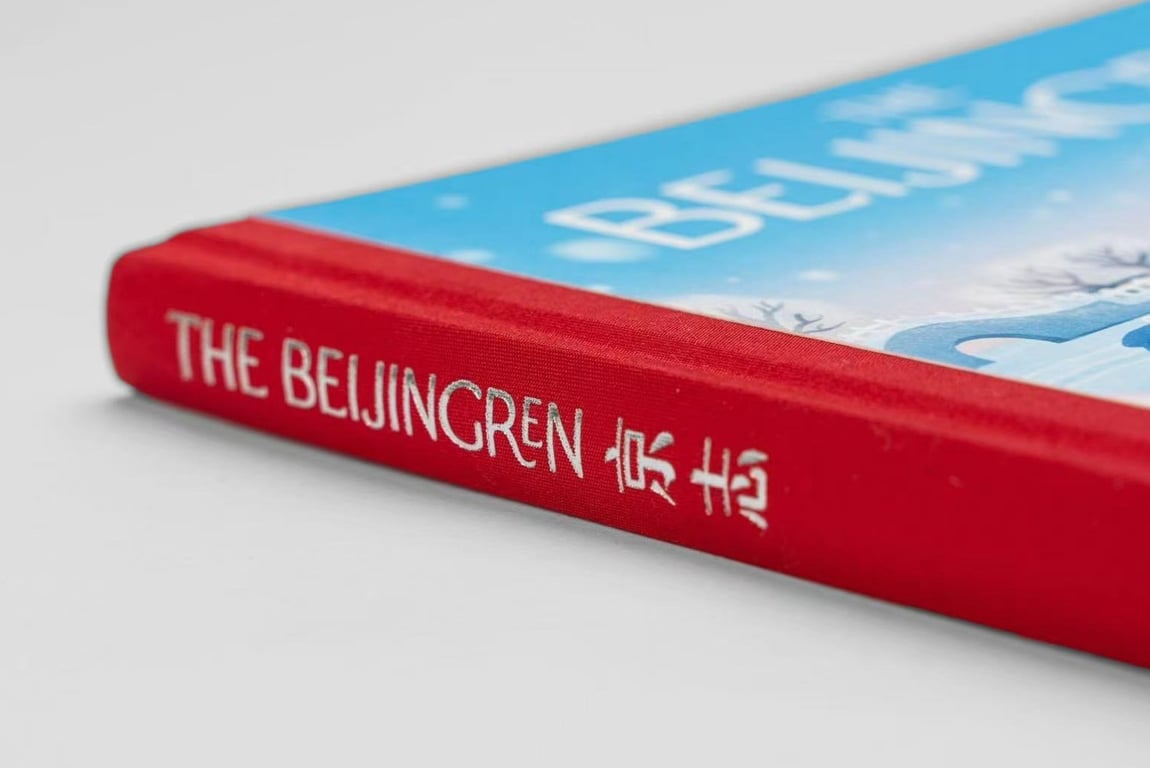

Albeit taking very different routes with their artwork, the aforementioned illustrators aced their assignments for The Shanghairen and The Beijingren. Respectively published in 2019 and 2022, the artbooks, which are the brainchild of Benoit Petrus and Vicki Jiang, take a page from the iconic publication The New Yorker.

While some have criticized the American magazine’s masturbatory model and its readership, an “insecure and anxious elite” who “took up The New Yorker because they saw it as a mirror of their yearnings for sophistication and style,” few can deny its contributions to the world, especially in the realm of design. Championing cosmopolitan sophistication, the weekly magazine gained recognition for its content, but especially for its illustrated covers.

Since ren (人) is Mandarin for ‘person,’ The Shanghairen and The Beijingren respectively translate to ‘the Shanghainese’ and ‘the Beijinger,’ Unlike their muse, however, both books chiefly contain cover art.

In order to realize their artbooks, Petrus and Jiang contracted some 80 artists to create visual love letters to two of China’s first-tier cities. In doing so, they have successfully demonstrated the need for more similar projects.

Besides showcasing urban Chinese life, The Shanghairen and The Beijingren support both fledgling and seasoned artists born or based in China.

“I believe the artists who participated in this art project are like me — busy in our daily lives. [Such projects] help me to calm down and to observe,” says Zhou, whose hectic schedule speaks volumes about China’s 966 working culture.

However, he believes that when youth get a chance to take a breather, their powers of observation are second to none: “They are full of passion and curiosity about their new surroundings. Also, they are more interested and proud of local culture, which is quite interesting.”

“What makes a young illustrator stand out from the rest? Or rather, why give a commission to a young illustrator?” muses Choi. The avid gallery-goer believes that young artists often bring something ‘new’ — not necessarily in terms of technique, but more in their thinking — to the table.

“I call this the ‘DNA of the times.’ The images, the language, and even the metaphors artists hide in their images are different for each generation,” says the part-time illustrator, who is just one in a handful of young artists who refuse to be put in a box.

She tells RADII, “I am surrounded by young illustrators and painters who are not necessarily full-time painters. Young artists have an explosion of creativity. Inspiration, joy, loneliness, and sadness can produce unique styles, squeezed out of non-art work and life.”

While The Shanghairen has sat on bookstore shelves for some years now, The Beijingren was unintentionally released just in time for Christmas this year (after a series of Covid-19-related setbacks). The ideal stocking stuffer or coffee table book, both rank high on RADII’s wish list.

All images courtesy of Benoit Petrus