“You could say that we live in the best of times, and the worst of times.”

Early in January I sat down for a virtual coffee chat with Xu*, a young tech worker who had recently been laid off.

Xu was born in 1993 and comes from a Chinese second tier city. Armed with her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from a leading liberal arts college in the US, she returned to China in 2016 amongst the millions of returnees rushing back to join the new tech boom. Mirroring her personal situation, many others who landed and found themselves at the peak of tech optimism in the late 2010s are now facing a very different reality post-Covid. It’s been estimated that since 2022, more than 28,000 employees have been laid off from China’s three largest tech firms (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent), and as of May 2023 overall youth unemployment for those aged between 16-24 in urban regions stood at 21%.

“Living in a first tier city like Shanghai, our savings at best can stretch for two to three months,” Xu lamented. Since being laid off, she has been actively searching for her next role within the tech space, but the current job market seems more competitive than ever before. With the inflation of education credentials and a cool-down of the Chinese tech sector, the market is now saturated with over-qualified talent.

In 2022, China’s college graduates exceeded 10 million for the first time, reflecting the emphasis that society places on education, but also a mismatch between labor market supply and demand. Young graduates lacking work experience and the means or desire to continue their studies face limited choices. Some have invented their own jobs as “full-time children,” whilst others have decided to take the plunge into the less glamorous service industry roles in coffee shops or hotpot chains.

While the older generation might still be measuring their career success in terms of asset accumulation or social status, the younger generation seems to be, more than ever, prioritizing meaning and individual satisfaction over anything else when it comes to their jobs.

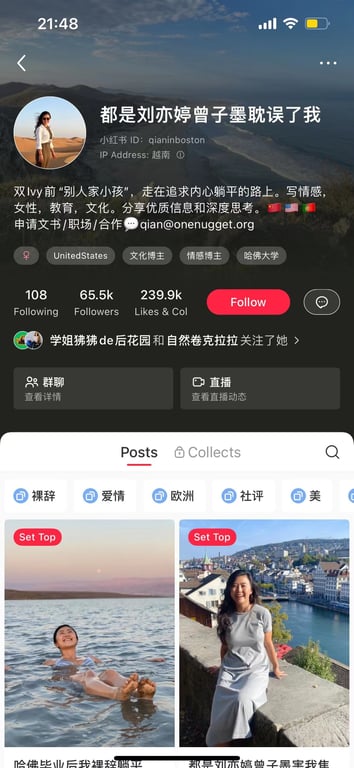

In 2022, Qian Zhang, a Harvard Business School and Dartmouth graduate with a string of accolades to her name, decided to quit her full-time job and pursue a different way of life.

“I realized that the conflict with the new management in my company was simply a catalyst, I just no longer wanted to wake up feeling anxious.” After a long career in tech and consulting, Qian decided to leave her high-powered role in the US and move to Portugal, with no particular plans except to start a new life altogether.

“My parents recently came to visit me in Portugal, and I think my father was shocked that this was not a phase, and in fact, I would not be going back to full-time work,” she reflected during our discussion. Qian feels that her generation, those born from the late 1980s to early 90s, is caught between two eras, having missed out on many of the initial benefits of China’s economic reforms and the greater social mobility of her parents’ generation (born in the 60s and 70s), while also being unable to “lie flat” like even younger generations.

On the flip side, Qian and her peers have also been able to craft success stories unique to the times they live in.

After documenting her journey on Xiaohongshu, Qian accumulated over 60,000 followers within the space of a few months, and has “accidentally” become an influencer for her own generation.

Qian writes about her life, thoughts, and decisions in her own distinct voice. The overwhelming response of her fans demonstrates how the critical choices she made deeply resonate with the demographic that she is part of.

Others affected by the layoffs at major tech firms have also discovered that the way forward might be outside of China.

Ming*, a 26 year old product manager, joined a company right after graduation and worked there for over two years, until he was laid off at the end of 2022. Prior to the layoff, he had heard rumors within his department about a headcount decrease, and actively tried to move to a different position within the large conglomerate.

“I wasn’t successful at the time, and there was definitely anxiety when I realized that I needed to look outside my current company for new roles.”

After debating job offers, Ming decided to join cryptocurrency exchange Binance for a job in Dubai, only to be laid off again in 2023.

“I think by this point I have accepted that there are many things outside of my control, and I just need to embrace change and make the most out of it.”

Since his departure from Binance, Ming has found that he’s able to parlay his location in Dubai and background in tech to serve as a cultural bridge and information source for the many Chinese businesses looking to enter the Middle East.

Ming is growing more confident of his choice, as he sees the Middle East as a land of opportunity, and finds that many business models which have already succeeded in China are just taking flight in Dubai.

“I definitely feel that there is no ‘one standard fits all’ anymore in terms of the best jobs, as compared to our parents’ times, and all I want to do is just to experience as much as possible at my age and see how I can leverage this platform for the future.”

Like Ming and Qian, millions born after the economic reforms of the 1980s are redefining what work and success can mean. China’s economic reforms have lifted 770 million people out of poverty, ensuring that this younger generation, unlike their parents, lives in a time of unprecedented access to material goods and daily conveniences. This also means that even when facing precarity, like Xu, today’s youths may have the choice to decide against taking what they regard as “bullshit jobs.” As the anthropologist David Graeber argues in his book of the same title, millions of people around the world — clerical workers, administrators, consultants, telemarketers, service personnel, and many others — are toiling away in meaningless, unnecessary jobs, and they know it. Whether due to the aftermath of Covid lockdowns or generational discord over mainstream values, what is certain is that younger generations are determined to set their own standards, and make a living out of it.

* Editor’s note: Xu and Ming are referred to using pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Banner image by Haedi Yue.