Feifei can’t recall the last time she shared her last name with someone new. Choosing not to be identified by it, she feels liberated from the social constraints that last names, inherited from family, often impose. To her, they don’t reflect who a person truly is.

In Chinese, “Fēi” (飞) means to fly, an action of breaking free from restrictions. Fei is her name and her philosophy, and she celebrates freedom and unconstrained femininity in her art, turning taboo subjects like periods and reproductive health into powerful and visually engaging statements. In the world of her imagination, women are unburdened by patriarchal repression.

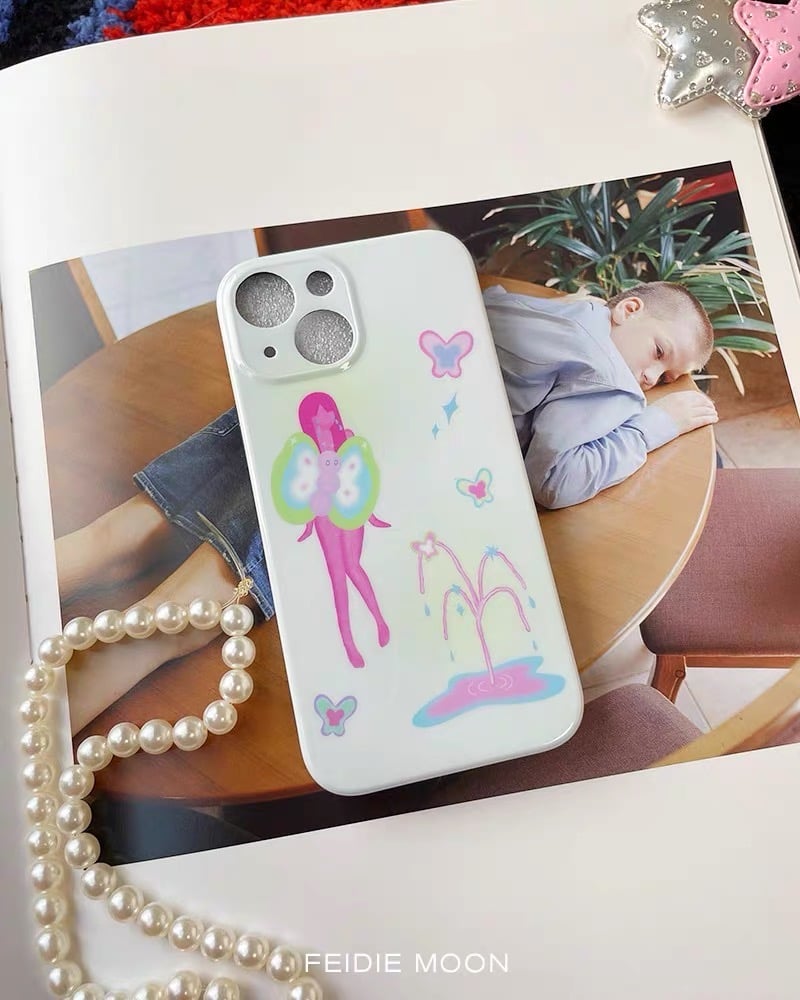

The 26-year-old Feifei is a self-trained artist living in Zhejiang province who puts her feminist paintings on phone cases to reach a wider audience. Despite never having attended college or formally studied art, she began doodling on an iPad in 2020. Though she occasionally posts her work on Xiaohongshu, she was put off by the platform after some users reported her posts for spreading “vulgar and pornographic content.” But on Taobao, she has accumulated nearly 40,000 followers over the years for her store Feidie Moon (飞蝶月亮, Fēidié yuèliàng). For her, creating art is an act of spreading love — a gentle love that everyone holds the potential for.

In one of her works, she painted a butterfly closely resembling the form of a vagina. Its shape also integrates the oviducts, emphasizing the connection to female reproductive anatomy. The butterfly symbolizes transformation, freedom, and the natural cycle of life, tying everything back to the themes of menstruation and womanhood. A star is positioned above the butterfly, representing guidance, hope, or the cyclical nature of menstruation, akin to the phases of the moon. Below the butterfly are pink droplets, which symbolize menstrual blood. These droplets seem to be falling onto a soft, pink sanitary pad. On either side of the pad, small white spheres symbolize the eggs or the idea of fertility, further connecting the image to female reproductive health.

She named the 2022 painting To See (看见, Kànjiàn), printed it on phone cases, and put them up for sale on Taobao.

As she writes on the product page, “See the sanitary pad, see the essential hygiene product for half of the world’s population. See the vagina, see the fallopian tubes, see the uterus and its regular bleeding. Face your own organs and natural biological processes without shame.”

“If any girl feels something from my art, no matter what or how much, I’d consider it a kind of force that challenges patriarchy. My contribution may not be powerful, but if I can be a small part of this collective push, I’d be very happy,” Feifei said.

Overcoming shame and silence

In her creative realm, period blood, and female bodies are blended harmoniously into nature, with elements like flowers and butterflies often appearing as symbols of growth, transformation, and fertility. These natural elements are carefully integrated into the feminine forms, blurring the line between human and nature, reinforcing the idea that womanhood and the natural world are intrinsically connected.

Menstruation is a recurring motif in Feifei’s work. Throughout history, menstruation has been a taboo topic that comes with shame and silence. In China, girls are taught not to speak openly about their periods, and menstrual products are discreetly wrapped in black plastic bags.

Feifei explained that her awareness of feminism led her to question the coded language surrounding menstruation, the secrecy of the black bags, and the silence surrounding the topic. As she learned from Sacred Child (神圣的孩子, Shénshèng de háizi), a feminist podcast on Xiaoyuzhoufm, menstruation has long been viewed as a powerful form of feminine spiritual energy, symbolized as the “flower” of the womb, representing fertility and life. The mystical and healing power of menstruation was hailed in shamanic rituals. However, patriarchal interpretations have overshadowed this sacred view, casting menstruation as taboo and impure.

While some ancient cultures revered menstrual blood, male-dominated religious systems have often labeled it as contaminating. This duality — sacred yet shunned — forms the basis of period stigma, which persists today. Societal pressure to hide menstruation, through euphemisms like “dà yímā” (大姨妈, “aunt”) and silence, reflects discomfort with this natural process, masking its deeper spiritual significance and undermining its positive cultural value.

To give one recent example of mainstream attitudes towards menstruation, in September 2022, the debate over the unavailability of menstruation products on high-speed trains sparked heated discussion on Chinese social media. A woman shared her frustration on Weibo about not being able to buy period products on the train when her period came earlier than expected. China Railway responded that feminine pads were a “private item” that was “not normally sold.”

Feifei’s The Flower of the Uterus (2022) was born out of the collision of period shame and the spiritual dimensions of menstruation. For this piece, Feifei’s imagination formed a whimsical garden where femininity is celebrated in its purest form. In the garden, women fly naked; flowers are the uterus, and dewdrops are period blood. In this pastel-colored land, women are free from any form of patriarchal pressure and fully embrace womanhood.

“Through a feminist lens, I’ve realized the various ways women have been unfairly treated — from ancient times to today, from structural issues to specific instances, spanning societal events, news, and even my own life experiences,” she said.

A male-dominated art world

According to the study “Female Art in Chinese Contemporary Art,” female artists express social views, emotions, and creative ideas from a distinct female perspective, often confronting and critiquing traditional aesthetic standards shaped by patriarchal norms. Despite the influence of foreign feminist movements, China has not yet experienced an organized feminist art movement similar to that which occurred in the West in the 1960s and 70s, leaving Chinese women artists in a passive societal position in a male-dominated art world. Historical standards have excluded women for not conforming to male tastes, but as more female artists emerge in the Chinese contemporary art scene, they are bringing delicate emotions and perspectives that challenge patriarchal standards and highlight the ongoing need for the recognition of female identity and rights.

“Not only in visual arts, women’s voices are rising in other creative mediums like poetry, music, and performance. Topics like menstruation, the uterus, sanitary pads, IUDs, the body, and breasts are becoming more normalized,” Feifei said. “Patriarchy is on the path to collapse, and we are witnessing this process unfold.”

Nature nourishes Feifei, calming her mind and spirit. In 2024, Feifei moved away from her previous home base of Hangzhou, Zhejiang’s capital. Now, residing in the mountains elsewhere in the province, she is renovating a farmhouse from scratch and cultivating her own land. As Feifei tries to find inner peace through an idyllic and self-sufficient lifestyle in the woods, she is reflecting on feminism and explores its deeper meaning.

“Feminist art isn’t limited to explicitly expressing feminist views in the work itself. The fact that women can pursue what they love in any field, regardless of whether their work directly expresses ‘feminist’ themes, is an expression of feminism,” she said.

Banner image by Haedi Yue. All other images via Feidie Moon.