Covid-19 has robbed us all of many things. For graduating art students in the UK, the toll has taken many different forms.

With degree shows cancelled and access to studio spaces cut, an educational promise has turned into confused attempts to deliver on opportunities that are essential to the UK’s cultural infrastructure.

Historically, university programs have proved to be an important entry point into the art industry. For many it’s not only a chance to develop their practice, but also an opportunity to access collectors, gallerists and potential patrons that will make careers in the art world possible.

With London now in its third lockdown, the closures that came in March 2020 feel a million miles away, but their consequences continue to take effect for students as a whole, and in unique ways for young diasporic and Chinese artists.

Growing Pains

For Hannah Lim, the transition out of school has been easier than she’d anticipated given the circumstances, although she has had to change her expectations for institutional support. The University of Edinburgh graduate got her Bachelors in Sculpture earlier this year, with her work drawing heavily on her British and Chinese Singaporean heritage.

“I’ve always been quite interested in Chinese mythology and philosophy because there’s such a rich cultural history,” she says. “Singapore’s such a new country, I’ve invested more in connecting with my Chineseness and tracing back that part of my family.”

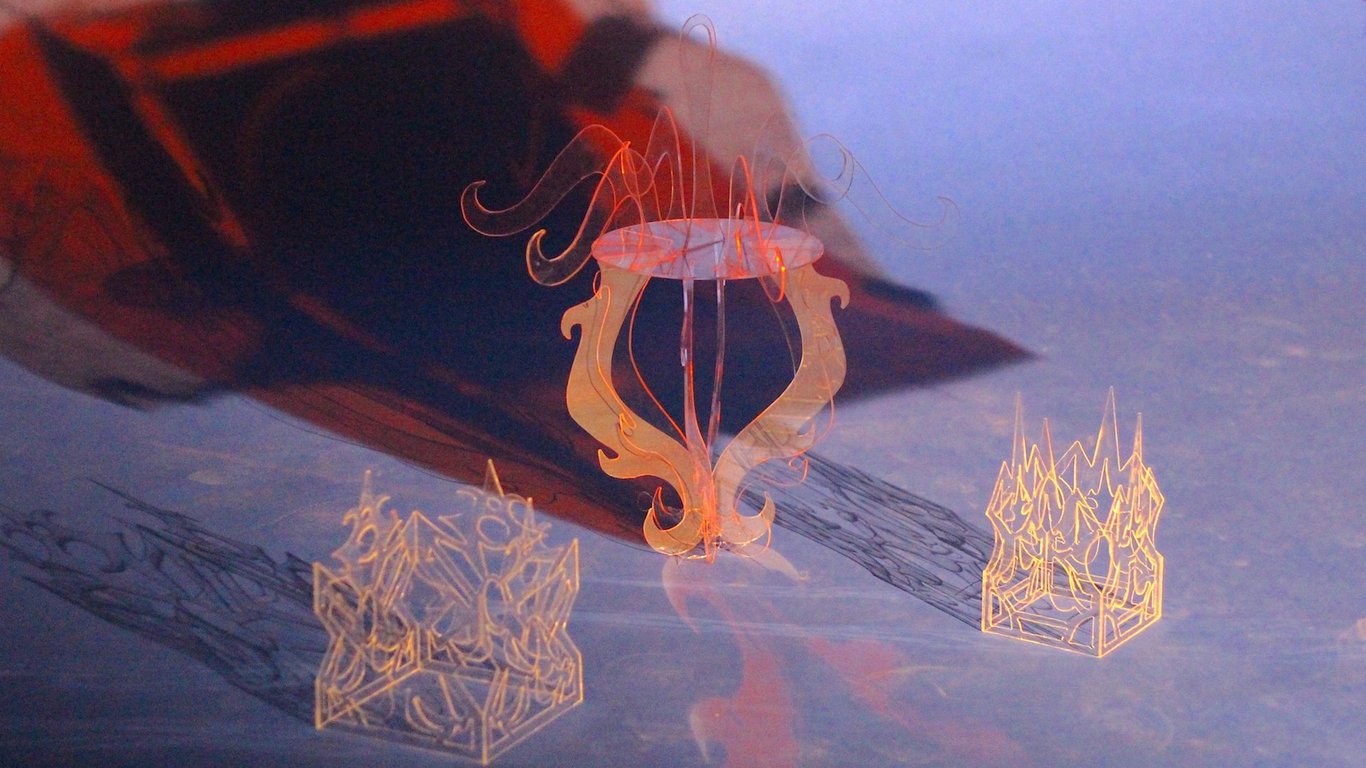

“Forbidden Gates” by Hannah Lim (2020)

Lim’s work focuses on large and symbolic gates, as well as hanging or standing sculptures that combine motifs from Chinese and European furniture design. Without access to studio space, she’s shifted her focus towards smaller objects that can be easily made and sold online, such as earrings, snuff bottles, and candle holders decorated with imagery found in Chinoiserie.

“I mostly make money through Instagram and my website,” Lim says. “For bigger pieces, I don’t really have the contacts to do that without a gallery, and that’s what you miss out on not having big degree shows.”

Degree shows often provide opportunities for full-on gallery support, giving artists access to continuous financial and networking resources. “Generally, it’s difficult for sculptors to get that representation, but for painters that tends to be something that happens, and this year I don’t think that’s been the case for anyone,” Lim says.

Lost Opportunities

For Qijun Li, that’s proven to be the case — though he doesn’t think he’s any worse off than his peers. Li moved from Sichuan to the UK when he was three years old, and after completing his bachelor’s at Leeds College of Art, spent a year working in a hospital to save up for a master’s degree at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London. With a focus on painting, his works combine elements of traditional Chinese culture and internet imagery in minimal, symbolically heavy canvas pieces.

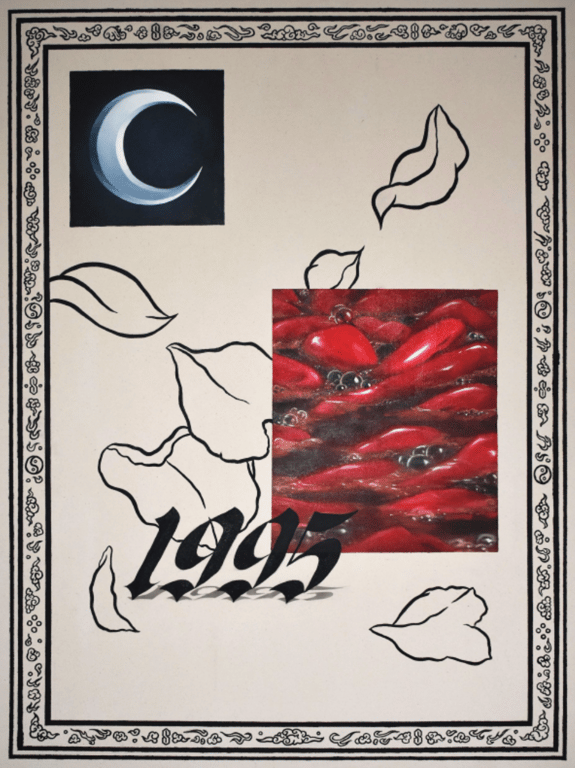

“Genesis” by Qijun Li (2020)

“Moving degree shows online definitely feels like a lost opportunity for all of us in the ‘fine art’ programs as we lose the ‘aura’ of the works, not being able to be in their presence,” Li says.

Like many universities, RCA ran all of their final degree shows online, hosted on websites not dissimilar to the ones they’ve used in previous years to supplement their physical exhibitions. With little time for universities to prepare and a platform that’s navigated in branches, the website interface doesn’t necessarily encourage exploration, making it difficult for students to showcase their work.

“During my degree, they talked about the importance of having high quality photos of your work, though it was up to us to find the equipment,” says Li. With the studios closed and the exhibition canceled, he’s had to adapt how he documents his paintings. Despite their strength and quality, he laughs telling me, “It’s hard to imagine them in a gallery context when I know they’re shot in my bedroom.”

Related:

New Neo-Realism: Liu Xiaodong’s Portraits of Chinese in Lockdown LondonLiaoning-born artist Liu Xiaodong and his neo-realist depictions of Chinese expats in London have added poignancy in the age of CovidArticle Nov 04, 2020

New Neo-Realism: Liu Xiaodong’s Portraits of Chinese in Lockdown LondonLiaoning-born artist Liu Xiaodong and his neo-realist depictions of Chinese expats in London have added poignancy in the age of CovidArticle Nov 04, 2020

A few institutions such as Saatchi Gallery and Carl Freedman Gallery have stepped forward to offer physical spaces for recent graduates, though only a few weeks ago the latter exhibition was cancelled. Fluctuating government regulations and moving timelines make planning anything difficult, and galleries are hard pressed to use their limited show time — and floor space — wisely. Sales need to be made and bills need to be paid, making established artists a safer bet than students or fresh graduates.

For now, Li is still waiting, hoping to cash in on promises and opportunities in the UK.

“I’ve had a few opportunities here and there, but it’s been crap to be honest,” he says. “I sold a few works through this online platform Where’s The Frame, but it’s just unfortunate timing […] I’m definitely someone who thinks art is best appreciated in person.”

Documentation During the Covid-19 Era

Grants and prestigious prizes have also been pushed into more competitive territory, such as The Woon Foundation Prize from Northumbria University. Given the impact of Covid-19, this year’s applications were suspended and will be combined with the incoming submissions for 2021.

Still, Hannah Lim remains optimistic. “Documentation has always been a really important part of the work I do,” Lim says of a facet of her practice that has managed to translate well to the digital landscape. “Early on in my degree, I liked to work with buildings, and being able to photograph them in a way where you can’t tell what the initial object was. Over time I’ve developed a certain style, and that wasn’t intentional. The process mirrors how I make my work.”

Photographing and documenting work has always played an important role in developing artists’ careers — today it feels essential. Applying for fellowships, grants, and open calls, one doesn’t ship pieces but sends written statements and images with the hope that it articulates something about how they will translate to physical space. Now, with more shows moving online, the image is the product — the documentation not just representative of the work, but rather a stand in for the work itself.

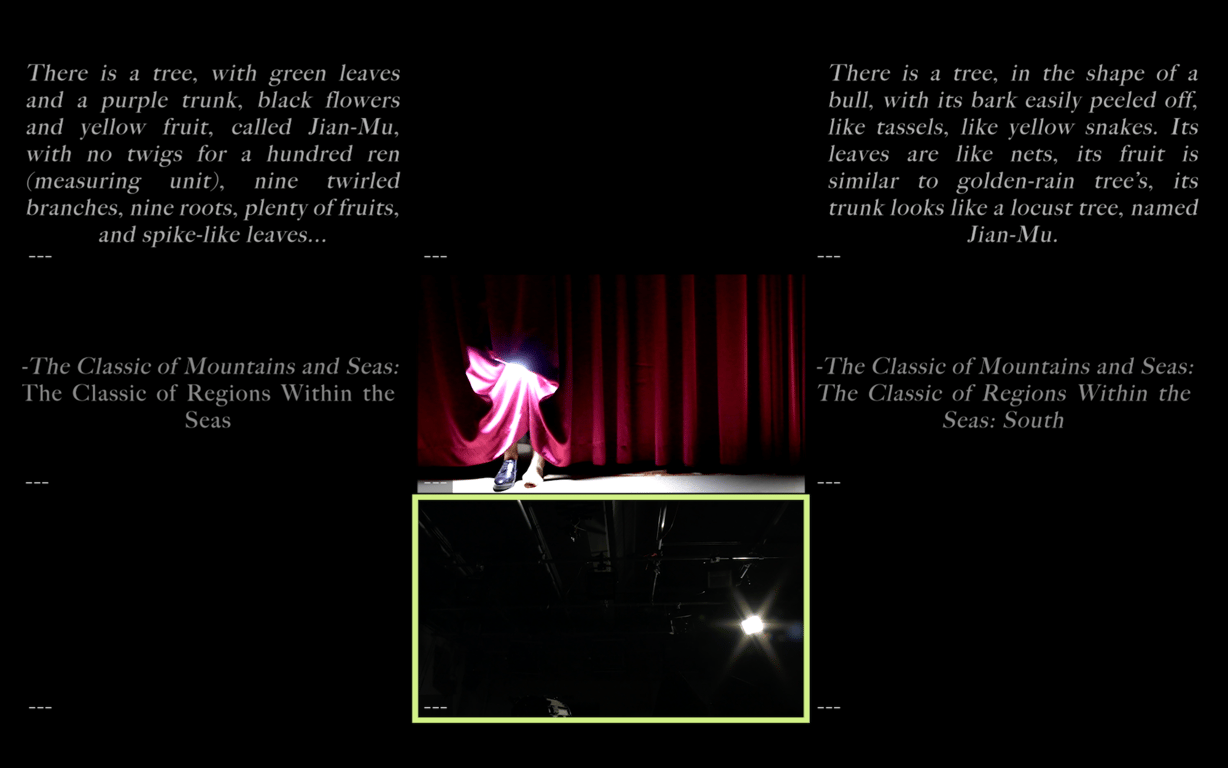

It’s something that’s forced RCA graduate Serena Huang to rely more heavily on film than she’d like. “Personally, I find video quite boring, but I can’t escape it,” she says. “Before, my practice was quite physical. I’m interested in object-first human interaction, reversing the hierarchy. If you sit in a position in your chair, it’s because the chair instructs you how to sit — even my video work was filmed with particular props in particular settings […] working with fragments of narration to link things together.”

Still from Sky Empty by Serena Huang (2020)

Since making objects and filming with actors is no longer an option for Huang, she’s turned to her archive and programs such as Adobe Create to build digital objects and make new, usable film content. Her recent performance Sky Empty took place over Zoom, and utilized various screens, real-time chat features, and multiple languages in a world-building, now-familiar format. “I’ve only really started thinking about the role of documentation […] it’s hard. It’s the hardest thing,” Huang says. “But it’s why video works the best, it’s a documentation in and of itself.”

Documenting evidence is something Huang has had to think about in multiple contexts. Born and raised in Guangzhou, she spent the last six years moving between China and the UK. After completing a bachelor’s at Chelsea College of Fine Art, she wanted to stay and work in England, but found no route that could keep her in the country legally past her degree.

After a year of saving through freelance design work in China, she returned to pursue a master’s at RCA, and recently secured a Global Talent visa, enabling her to live and work in England. These visas granted by The Arts Council England depend on ample evidence, including show reviews, photos, exhibition histories and more — evidence Huang was collecting from the start. She says her visa application was processed more quickly because of Covid-19 and that she has found teaching opportunities through her alma mater and through her current Post Graduate Certificate, but she’s still eating through her savings.

Difficult Choices

While those that have been documenting their careers with a commitment to stay in the UK may have found themselves in a similar position to Huang, other Chinese students were faced with a difficult decision: finish out their degree in the UK and risk not being able to get back to China, leave early and graduate at a distance, or postpone their programs and face substantial financial penalties.

Between visa processing fees, flights, housing contracts, and more, the costs for international students taking time off from their degrees are immense. For many, what they’ve been left with are challenging choices and a series of images — merely documentary proof of their time and their work over the last couple of years.

Cover image: “In Praise of Shadows” by Hannah Lim (2019). All images courtesy of the artists.