As the UK moves into its second nation-wide lockdown this week, as a result of a second wave of Covid-19, restaurants, pubs, non-essential shops and art galleries once again close their doors to the public, with no fixed idea of when they’ll be able to reopen. For galleries, that means canceled openings, programming being pushed back, and the possibility that shows that have to prematurely end may or may not see an extra lease of life on the other side.

For Liaoning-born artist Liu Xiaodong, it means a curtailed exhibition and an early closure for his show at Massimo De Carlo in London. His show, “New England,” was set to close on November 21 but has proven to be a collection of work that’s increasingly taken on the weight of present occurrences over the past few months.

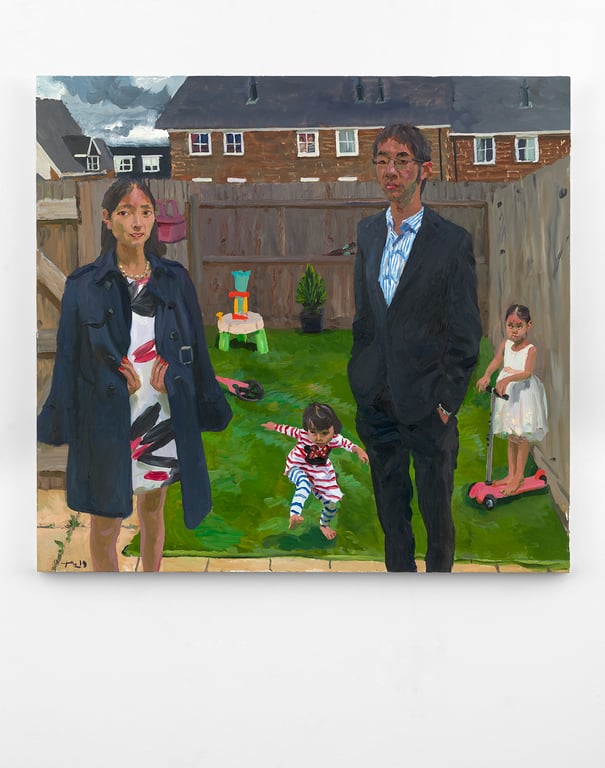

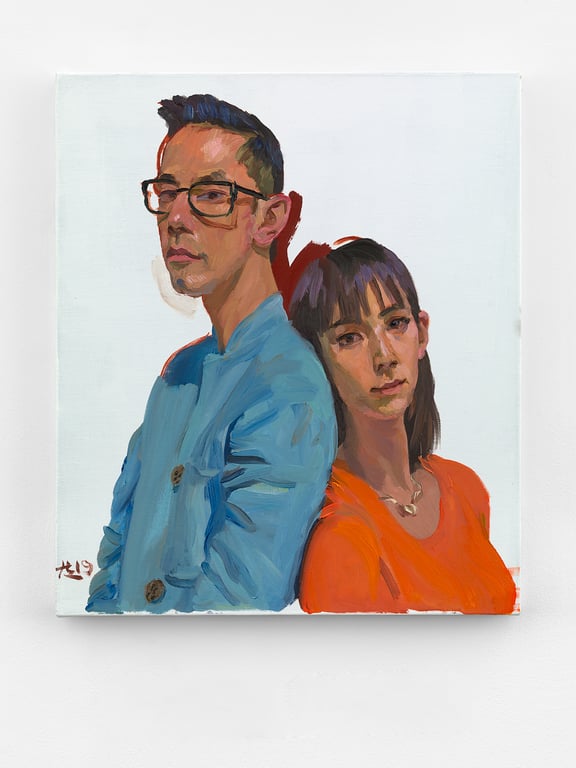

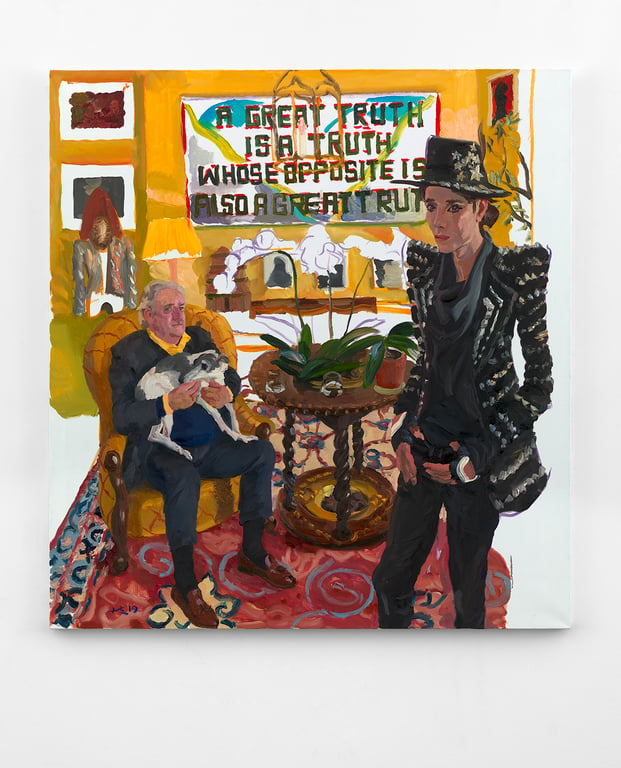

A fashion designer, a polo player, a forlorn man reclining nude on his couch — these large portraits of Chinese expatriates fill the walls of the gallery. Organized long before the world began to close its borders and look inward, these rich snapshots of London’s well-to-do are framed by richer tapestries, speckled with champagne bottles, wallpapered with expensive art, and housed in more expensive suburbs. The large-scale oil portraits of men, women and children capture the sitters in their homes, backyards and self-made work environments, depicting what these people have made for themselves and of themselves. The exhibition is accompanied by a documentary of Liu’s process and the sometimes curt, jarringly honest exchanges that take place between him and his subjects.

Geofrey and his Family (2019)

Known for his Neo-Realist painting, Liu was invited by the gallery to come to London in 2018 to see if he was interested in realizing this body of work. “They were all friends of the gallery, and I later realized they all knew each other in some way or another,” Liu tells me over email. “London is one of the most expansive cities in the world — how do all these British Chinese live there? And such comfortable lives too. I was curious about this aspect.”

One of the more striking elements of the exhibition is that so many of the paintings take place in the subjects’ homes. These intimate moments in Liu’s sitters’ living rooms or backyards have ended up foreshadowing a reality none of us could have anticipated: lots of time indoors. It also brings to life the melancholy behind the thousands of people facing unemployment, eviction, and increasing debt as the pandemic continues.

Vic&Ed, Brother and Sister (2019)

In a post-Brexit England — and arguably around the world — these anxieties are often displaced on people of non-white ethnicity, and with political figureheads flouting phrases like “kung-flu”, it’s no wonder The Guardian reported back in May that Covid-19 had triggered a 21% rise in hate crimes against south and east Asian communities in the UK. Increased reports of hate crimes against ethnic Chinese in the UK track back to February, with students in Southampton citing experiences of violence and verbal abuse, levied at them for wearing face masks in public.

Related:

Coronavirus Stirs Rumors and Racism Towards Chinese Eating Habits and HealthOn social media, ignorant rhetoric about food and health is spreading faster than the virus itselfArticle Feb 03, 2020

Coronavirus Stirs Rumors and Racism Towards Chinese Eating Habits and HealthOn social media, ignorant rhetoric about food and health is spreading faster than the virus itselfArticle Feb 03, 2020

2020 has seen the UK facing a reckoning when it comes to its whiteness, and the name of the show “New England” adds to the charge. “These are new immigrants, and ‘New England’ is also a humorous reminder,” Liu writes.

Referencing the former British colony in the United States that emancipated itself, born of the crown and grown into a rebellious child that runs away from home, the name choice has a quasi-colonial karmic action, something elaborated upon in the exhibition text by Mark Rappolt. “It’s a region that […] sparked a resistance to received ideas of England and Britishness, a resistance that led to the eventual expulsion of the English/British, the cutting of ties with the old monarchy that had granted the land its name,” writes Rappolt, “all of which is now memorialized in the name of the local American football team — the New England Patriots.”

But even with this cheeky reclamation and complication of identity, the particulars of “Chineseness” for many of Liu’s sitters manifest in a number of ways, especially now.

Duncan and his Qiumles (2019)

“While painting on-site abroad over the years, I did portraits of Chinese that belong to two different social classes: the rich, and the working class. I rarely talked with either of them about identity,” Liu explains. “The environment where a person lives or works tells me a lot about them.”

Spending hours, days in their homes, Liu and his sitters cover a lot of ground, sharing their own experiences of life, their families, how they spend their time. Liu’s role is one of the interpreter, keeping a diary to track his own thoughts and feelings throughout his process. Directly discussing identity may not be the best, or most honest depiction of how these people see themselves. It’s Liu’s job to read between the lines, couch cushions, bookshelves and lingering silences.

While this body of work focuses on friends of the gallery — the successful and established coming from well off families — Liu’s decades of capturing Chinese people in their natural environments has connected him with countless numbers of individuals and communities, inside and outside the PRC. “Chinese overseas are being badly affected by the pandemic,” he says. “If they obtained citizenship where they live, regardless of where that is, it means that they cannot come back to China just like any other foreign national.” China does not recognize dual citizenship, and the country’s intense border regulation and travel bans from foreign countries over the course of 2020 have further complicated such travel. In securing citizenship from another country, a Chinese national must relinquish their passport, meaning that, “Even if their parents were to pass away, it would be extremely difficult to be granted visas to come back.”

Veronica and her Twins (2019)

Turning back to the large-scale portraits, there’s both a beauty and an emptiness captured by their cluttered things, the negative space, and for many of the subjects, sad eyes. Liu’s categorical genre of painting, “Neo-Realism,” is perhaps the perfect presentation for his subjects as well, the genre itself having a complicated history that fits the moment.

The first wave of Realist painters in China are often traced back to the late 1800s. Having pursued formal art training in cities like Paris, the Contemporary narrative all too often leans on a “West to East” unidirectional influence that is further co-opted by Chinese Realists’ relationship to state-backed art initiatives. These painting skills were deployed throughout the Cultural Revolution in the form of Socialist Realist propaganda, a style which characterizes the now world famous — albeit slightly fetishized — posters attributed to the era. This all changed after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, and free to turn away from explicitly political subject matter, the “Neo-Realists” were born.

In a 2007 New York Times interview with the then head of sales for 20th-century Chinese art at Christie’s Hong Kong, Vinci Chang describes Neo-Realist artworks as “rich, moving depictions of the feel of daily life [that] examine with a humanitarian eye the unaffected simplicity and beauty of local scenes.” In focusing on the beautification of an environment, there’s an elevation of the day to day that takes place, historically rooted in the glorification of labor and agrarian or industrial practices.

It’s simultaneously luxurious and humble, a celebration of Chinese people. Having depicted both the working class and the well-to-do, with this celebration comes the opportunity for critical reflection, a duality present in Liu’s recent body of work and the lives of Chinese expatriates overseas in the age of Covid. With the beauty of his inherent subject matter apparent and easily available, Liu’s work leans less in the direction of glorification, more grounded in a complicated present that’s charged with the challenges facing Chinese abroad, regardless of creature comforts.

Ma Yue’s Home (2019)

In the catalogue Rappolt writes that, “Cumulatively, the various scenes in ‘New England’ lead us to wonder what migration and integration mean. The individual or the environment: who changes what? […] In the age of mobility and globalism perhaps it doesn’t matter where people are or where they come from.”

Of course, in the age of Covid, globalism has taken a backseat, and these works highlight that maybe the “global” that we imagined is more figment than fact. When explaining the difference between the classes of people he’s worked with, Liu writes, “The rich apply for citizenship because that makes their lives easier, it makes traveling more convenient. They are citizens of the world after all. The reason why working-class people do it is different — because it makes them feel safer, they can apply for better jobs.”

But for now, these portraits and their subjects aren’t going anywhere, and sit locked behind the closed doors of Massimo De Carlo, awaiting the day when visitors could have returned to see what “New England” really looks like, the rest of us waiting with them.

Liu Xiaodong: New England, at Massimo De Carlo London, October 7 – November 4, 2020

All works by Liu Xiaodong, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Massimo De Carlo, Milan/London/Hong Kong