China’s hit rap competition The Rap of China has been making plenty of noise this month, with its fourth season debuting on Friday, August 14 on China’s Netflix, iQIYI. The latest season has also brought the question of so-called “dialect rap” back into the national conversation, after an incident got netizens talking online.

Guangdong rapper SOULHAN auditioned for this year’s The Rap of China rapping in his native Cantonese, but a new judge on the show, Mandopop star Jane Zhang, asked if he had provided a Mandarin verse instead. The rapper did not have one, and SOULHAN did not earn a place on the show in the end. The incident stirred up anger on Chinese microblogging platform Weibo after SOULHAN posted about the incident.

One of the most upvoted comments under his post implied that the show was out of touch, saying, “A hip hop TV show asking Jane Zhang to join is already very un-hip hop.” In China, Zhang is best known as a Mandopop singer, but has collaborated with rappers such as Big Sean.

“Why are Cantonese songs not okay?” wrote another.

Related:

Kris Wu, GAI, Jane Zhang, Will Pan and Jay Park Team Up for “The Rap of China” 2020 CypherAnticipation for the launch of “Rap of China 4” is rising, as the judges on the show team up for their newest cypher, “RAPSTAR”Article Aug 11, 2020

Kris Wu, GAI, Jane Zhang, Will Pan and Jay Park Team Up for “The Rap of China” 2020 CypherAnticipation for the launch of “Rap of China 4” is rising, as the judges on the show team up for their newest cypher, “RAPSTAR”Article Aug 11, 2020

Speaking about the incident, SOULHAN told RADII, “I respect the decision made by Jane Zhang. In recent years, people have lost faith in Cantonese rap, as more and more people believe only Mandarin hip hop could attract traffic. But I will continue to engage in efforts in promoting Cantonese rap and make it work.”

Similarly in the opening episode of the second season of rock music-focused variety show The Big Band, Guangdong folk rock group Wutiaoren decided to change their performance at the last minute. Scrapping their pre-planned Mandarin language song, they instead performed “Doshan Boy” (Daoshan Liangzai 道山靓仔) sung in the dialect of small-town Haifeng, in east Guangdong province.

The exact reason behind the change was unclear, though some speculated that it may have been an act of rebellion against the judge’s preference for Mandarin-language songs. Wutiaoren were given a low score and were initially supposed to be eliminated from the show, but were later brought back.

Shows like The Rap of China and The Big Band have made no bones about the fact that they prefer Mandarin lyrics over regional languages such as Cantonese or Shanghainese, as they aim to appeal to the mass market.

However, as these forms of underground music have increasingly found itself pushed into the spotlight on streaming platforms like iQIYI, musicians performing and writing in regional languages have been forced by necessity to sing in Mandarin, or have been pushed to the sidelines.

“The commercial value of Mandarin music appeals to the media, and that explains why Mandarin songs are preferred predominantly on TV programs,“ Zhou Yulou, a senior linguistics student at Stanford, tells RADII. Zhou also participated in the now-defunct dialect music variety show 1.3 Billion DB in 2016, a key example of how music using regional languages and dialects has struggled to gain a hold on modern media.

Produced by iQIYI and first aired in 2016, 1.3 Billion DB (十三亿分贝) invited people to sing songs in languages and dialects from their respective regions of China. While the show garnered positive feedback from its audience, it was discontinued the following year, as it struggled to bring in online traffic nationwide compared to other entertainment TV programs.

The Push for Mandarin in Media

China’s efforts to promote Mandarin as its primary language began as early as the founding of China in 1949. In 2019, the penetration rate of putonghua (普通话) — the modern, standardized form of Mandarin language, adopted for use as the common language in China — had reached over 80%, compared to that of 53% nearly 20 years ago in 2000.

Earlier this year, short video and video streaming platform Douyin (the TikTok equivalent in China) reportedly banned video-bloggers from using languages other than Mandarin during live streaming, warning users to “take care of different language needs” across the country.

Related:

Is China’s TikTok Equivalent Banning People from Speaking Cantonese?Douyin is allegedly forcing some creators to speak Mandarin instead of Cantonese while livestreaming and recording videoArticle Apr 03, 2020

Is China’s TikTok Equivalent Banning People from Speaking Cantonese?Douyin is allegedly forcing some creators to speak Mandarin instead of Cantonese while livestreaming and recording videoArticle Apr 03, 2020

The entertainment industry has closely regulated the use of dialects as well. As early as 2005, China’s National Radio and Television Administration created a dialect ban for all TV dramas except for “special needs,” such as in the case of regional operas like Sichuan opera. The mixing of English words with Mandarin has also been discouraged elsewhere, with the justification that it might disrupt the overall quality of TV programs.

Interestingly, the film industry has been able to escape this trouble to an extent as regulations have tended to be less stringent for movies. In the past two years, there has actually been a growth in movie productions that use local languages and dialects. According to statistics from People’s Daily, there were around 20 domestically-produced movies in 2018 and 2019 that used local dialects, a noteworthy increase compared to previous years. In particular, a couple of well-known Chinese directors have seemingly favored dialect language in their works — Jia Zhangke’s 2018 hit film Ash is Purest White uses Jin Chinese dialect from Shanxi province, while rumor has it that award-winning Hong Kong based film director Wong Kar-wai’s first-ever TV series Blossoms Shanghai will be filmed entirely in Shanghainese.

“I feel the next ten years could be the last period of growth for dialect music and dialect-based new media,” says Zhou. He adds that he believes “dialects might become a symbol of regional culture, and will survive in areas where cultural identity is strong” but that the role of dialect music will eventually “become similar to that of opera [in China]” — largely seen as a high-brow art form, rather than appealing to the mainstream.

How Similar are Dialect Languages to Mandarin?

Some regional languages have found success, however, within the mainstream market. The languages of Sichuan and Chongqing — two of the newer epicenters of Chinese hip-hop — have increasingly had a greater presence in music as prominent rappers from the region gained national recognition. Rap crews CDC from Chengdu and GO$H from Chongqing are among the most famous and well-respected rap crews in the country.

Related:

Get to Know China’s Biggest Regional Rap Crews Ahead of “Rap of China 4”Chengdu is perhaps best known as China’s capital of rap, but these regional crews show how hip hop is flourishing in major cities all over the countryArticle Aug 05, 2020

Get to Know China’s Biggest Regional Rap Crews Ahead of “Rap of China 4”Chengdu is perhaps best known as China’s capital of rap, but these regional crews show how hip hop is flourishing in major cities all over the countryArticle Aug 05, 2020

One reason that could account for Sichuan and Chongqing’s popularity is the similarity of Sichuanese (spoken in Sichuan province and the neighboring metropolis of Chongqing) to standard Mandarin. Both belong to the general Mandarin (or guanhua 官话) category and share around 48% of the same vocabulary; most words in Sichuanese are also phonologically similar or identical to Mandarin, apart from the tones. Therefore those who understand Mandarin are most likely to capture the meaning of Sichuanese by paying a bit more attention.

But regional languages from southeastern China, such as Cantonese and Shanghainese, are drastically different from standard Mandarin, setting language barriers for audiences outside of these areas. (Cantonese, for instance, sounds completely distinct from Mandarin and has six tones, while Mandarin has only four.)

This linguistic difference can in some ways help account for the limited spread of Cantonese rap in China, compared to the more widespread Sichuanese rap music, though Cantonese is the third most spoken language in China, with more than 90 million native speakers. While Cantonese language music was all the rage in the ’90s — in the form of iconic Cantopop — interest from the music industry has gradually shifted to the Chinese mainland, with idols from Hong Kong such as Kris Wu, G.E.M., and Jackson Wang focusing their efforts on Mandarin language songs for a mainland Chinese audience.

It is worth looking at Shanghainese in this context as well. Perhaps because of the city’s distinct geopolitical significance, as well as a push for its revival by local communities and government, there has been a trend in Shanghai to protect Shanghainese through both bottom-up and top-down approaches. Local public schools have been setting up Shanghainese language lessons as early as kindergarten, while Shanghainese-speaking teachers have been employed in all elementary schools.

Local Music and Personal Stories

As music genres like hip hop go global, drawing from a mixture of different cultural elements and influences can be a potent force for artists looking to make a genre their own. Perhaps most importantly, artists using local languages can help get their stories right — as a substantial amount of rap content focuses on personal stories.

Zhou posits that the market for music in languages such as Cantonese is out there, referencing Mongolia in this context, which has a population of only three million people but can nevertheless support its own music industry. The trouble in China is perhaps the sheer number of regional languages and dialects throughout the country, as well as its government’s decades-long push to make Mandarin its common language. “China is a homogeneous market,” Zhou observes, “and media wants to profit from its audience nationwide.”

For that reason, it’s hard to understate the role that TV shows like The Rap of China and The Big Band play in the survival of regional languages and dialects in popular music.

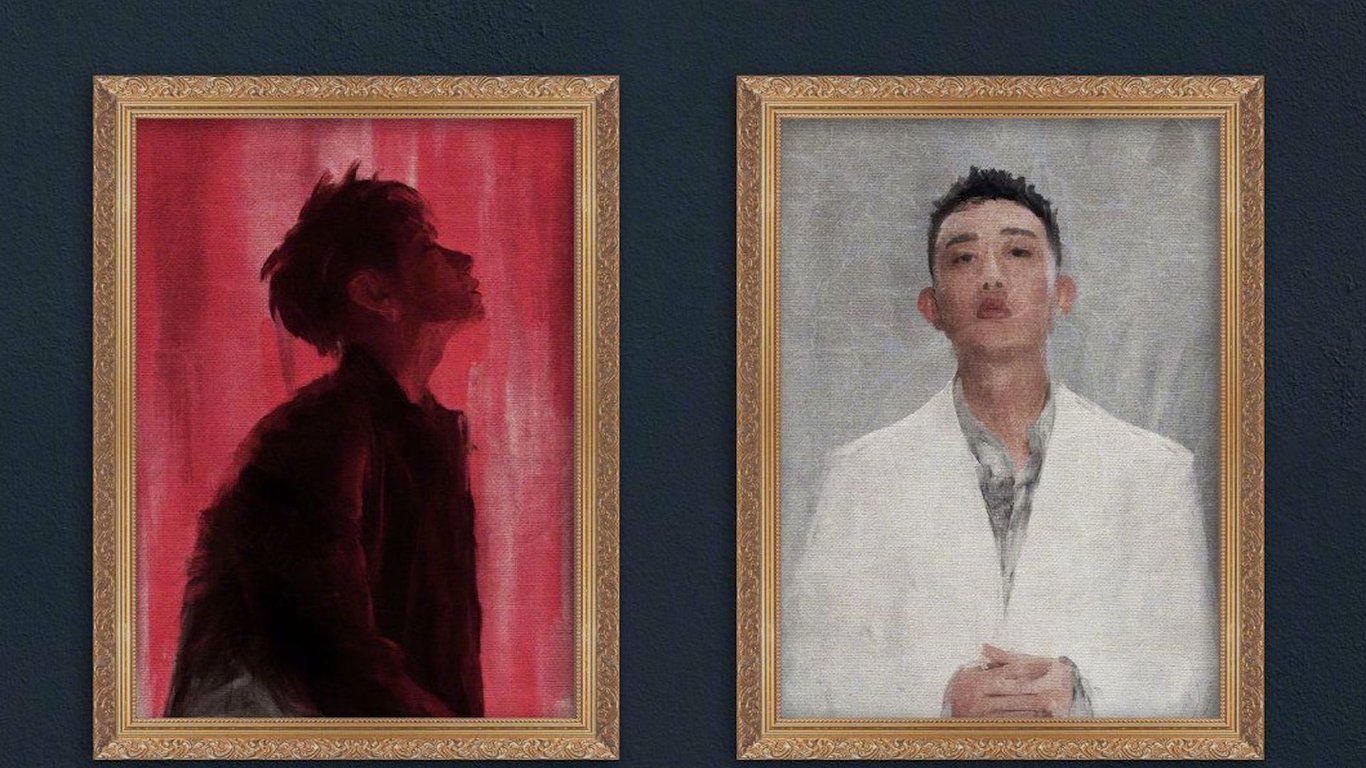

Header image: Guangdong rapper SOULHAN