Lexie Liu has the look and swagger of a complete pop star, Nick the Real and ICE have had audiences swooning, and Kungfu Pen impressed with his attempts to stay true to his craft amid the commercial swirl, but the real break out star of hit hip hop show The Rap of China‘s second season has been Xinjiang rap.

Regardless of whether the two remaining Xinjiang contestants ultimately triumph in this weekend’s final, 那吾克热 Nawukere (also known as Lil Em) and 艾热 Aire (aka Air) have both shown considerable ability on stage and magnanimous personalities off of it. Together with Majun 马俊 (Max), who was booted around halfway through this season, they’ve shone a spotlight on a hip hop scene that much of Rap of China‘s audience may have been previously unaware of. (Last season featured two rappers from Xinjiang, but both were of Han ethnicity; and of course, the actual scene extends well beyond the MCs who make it to a mainstream TV show.)

That development has come at an intriguing time, to say the least. Away from the sponsorship deals and vapid Kris Wu-isms of Rap of China the Xinjiang region’s predominantly Muslim Uyghur population has been in the headlines for some very different reasons. Since last year, Megha Rajagopalan, who was Buzzfeed News‘ China bureau chief, has been reporting on what the publication has called “dystopian” policies in the largely Muslim region that have turned it into a “21st century police state“. In recent months, other international titles have followed suit, while some US lawmakers have urged sanctions due to what they claim to be “arbitrary detention, torture, [and] egregious restrictions on religious practice and culture” in the region.

Chinese State media has disputed such depictions. The Global Times admitted that “police and security posts can be seen everywhere in Xinjiang,” but said that this was “a phase that Xinjiang has to go through in rebuilding peace and prosperity and it will transition to normal governance.” Under a headline of “Xinjiang policies justified“, another article in the same publication stated that the “Chinese government’s ethnic and religious policies in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region have given priority to anti-secession and counter-terrorism so as to maintain stable development, and Western media should see the situation themselves before accusing China.” A week after that article was published, Rajagopalan’s attempts to renew her journalism visa were rejected by the authorities and she was forced to leave the country.

China mounts publicity campaign to counter criticism on Xinjiang https://t.co/n5zXNKjRVw via Ben Blanchard @baibinbeijing & Tom Miles @tgemiles

— Reuters China (@ReutersChina) October 2, 2018

Against this backdrop, not to mention the apparent disappearance in May of “Uyghur Justin Bieber” Ablajan Ayup, the rise of The Rap of China‘s Xinjiang contingent to prominence has been laced with intrigue. Of course, it can be dangerous to read too much into a heavily commercialized, often frivolous TV show, in a climate where mainstream media productions are regularly used to reinforce political messages, the connotations are certainly interesting. And this particular show had a significant impact on mainstream culture when it first emerged.

Season two of Rap of China has not been quite the sensation that season one represented — the real TV hit of the summer has been another iQIYI property with its own fascinating undertones, Yanxi Palace — but it’s still been a major ratings player. After the controversy that enveloped its season one champions, the show has been at pains to be very on message for season two. It’s not been as blatantly subservient as Hunan TV’s quiz based on Xi Jinping speeches, but both judges and contestants (tattoos covered) have emphasized “positive energy” and the promotion of “Chinese culture” in every episode.

Related:

Kris Wu Drops Patriotic Single “Chinese Soul” Ahead of “Rap of China” ReturnArticle Jul 12, 2018

Kris Wu Drops Patriotic Single “Chinese Soul” Ahead of “Rap of China” ReturnArticle Jul 12, 2018

A message of “integration” and of Xinjiang being an inalienable part of China has lingered whenever the rappers from that area have featured prominently in the show — which has been a lot as the season has worn on. They’ve been allowed to drop verses in the Uyghur tongue, but their songs and dialogue have still been dominated by Mandarin and throughout there have been utterances about the promotion of “Chinese culture” and “creating a Chinese hip hop”, in line with those from the show’s Han Chinese rappers. One of Nawu’s tracks, available to stream on iQIYI’s Rap of China hub, ends with the words “I’m from Urumqi Xinjiang, and I’m made in China”; a song he performed with fellow contestant Al Rocco on the show featured the “made in China” phrase prominently.

Such “made in China” rhetoric has felt almost a requisite for performers on this season of Rap in China, but the Xinjiang rappers have not held back from giving their home region a shout out as well, in the time-honored hip hop tradition of repping where you come from. In episode 11, where rappers who had previously been knocked out of the contest were brought back for a “resurrection” round, one of Kashgar-born Aire’s key songs was entitled “West Side”, with a chorus of:

Show your respect to the brothers from the west side

We bring the good things all the way from the best side

You know we earned it

Everything we want

Everything we got

We earned it

Producers regularly cut to Nawukere, already assured of his place in the final, smiling and cheering unreservedly as Aire defeated all the other contestants in the “resurrection” competition via a stirring string of 1v1 battles to join him in the grand finale:

To be fair to the show’s producers, on the face of it the Xinjiang contestants have largely been treated the same as the other rappers. And thankfully, to date at least, there’s not been a fetishization of Uyghur culture of the kind that is rolled out annually as part of CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala, “the most watched TV programme in the world” which regularly features patronizing and/or offensive portrayals of China’s ethnic minorities.

It’s also hard to argue that the two Uyghur rappers are not in the final round on merit. Despite some Kris Wu-driven melodramatic silliness (which is pretty standard for the show) early on, Nawukere — who was previously a contestant on CCTV’s Sing My Song show — has been easily identifiable as one of its main talents from the very start. Aire too has gotten this far on the back of being a consummate performer, ably switching between impassioned bars on tracks such as “Had Enough” and softer balladry dedicated to his mother and wife.

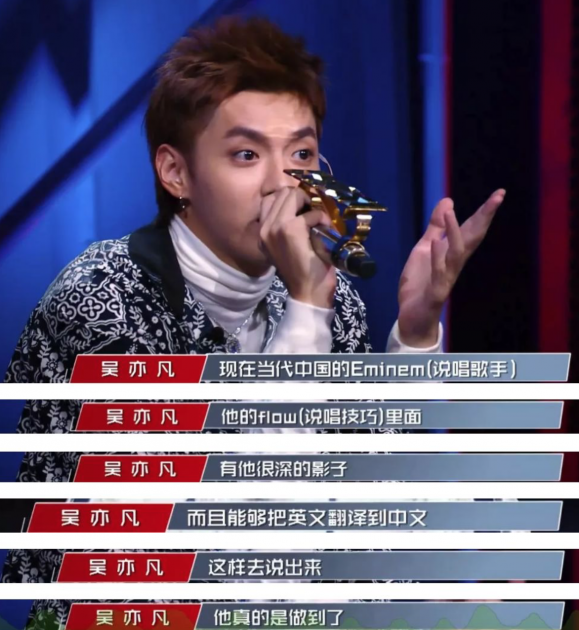

Nawu, who started his rap career by doing Eminem covers in 2006, was recognized by Kris Wu as “China’s Eminem” in one recent episode, while Wu’s fellow judge Will Pan repeatedly spoke of Aire’s “genius” as the latter destroyed the competition in the “resurrection” round.

Kris Wu offers his considered opinion on Nawukeri

Nawukere seems particularly well poised to become The Rap of China‘s season two champion, although given it’s a reality show inclined toward drama as much as music it can be hard to predict. If either he or Aire triumphs neither will be an undeserving winner. But neither will it be possible to avoid the subtext if a Uyghur contestant wins one of the country’s biggest television shows, given what is currently happening in Xinjiang.

—

You might also like:

What the “Uyghur Justin Bieber” Tells Us About the Subtle Politics of PopArticle Jun 22, 2017

What the “Uyghur Justin Bieber” Tells Us About the Subtle Politics of PopArticle Jun 22, 2017

Where are They Now? “Rap of China” S01 Champs Hit the Silver Screen and Beef OnlineArticle Aug 13, 2018

Where are They Now? “Rap of China” S01 Champs Hit the Silver Screen and Beef OnlineArticle Aug 13, 2018