Alternative Visual Archive is a monthly RADII column that spotlights films or film culture that interrogate otherness and strive for an alternative to the narratives found in the mainstream.

Every July and August, two-thirds of China is subjected to blistering heat, but one region is exempt from the torrid temperatures: The Tibetan Plateau. Virtually heatproof, the ‘Roof of the World’ is usually a comfortable 20 degrees Celsius (68 Fahrenheit) during the summer, making it the ideal place for miscellaneous gatherings.

In a stroke of irony, the reason for the temperate weather is also a hindrance to the region’s development: the high altitude makes it somewhat disconnected from the rest of the country, economically, socioculturally, and geopolitically.

Xining city is known as the eastern gateway to the plateau and as a pilgrimage site for many young filmmakers in China come late July. The oft-overlooked city has gained attention thanks to FIRST International Film Festival, an ad hoc incubator for young, rising names in Sinophone cinema. In addition to hosting a main competition and exhibition segments, FIRST also offers spin-off services such as financing young filmmakers, hosting filmmaking workshops, and connecting amateur filmmakers and established film distributors.

For this reason, the Chinese title of the festival, which translates to ‘FIRST Youth Film Exhibition,’ does the annual event more justice.

Cinephiles will note that FIRST shares similarities with Sundance Film Festival in Utah, U.S.: Firstly, both festivals happen off the beaten track, in hilly, frontier regions, away from the geopolitical nuclei of their respective countries. Secondly, they strive to promote young voices in the film industry while spotlighting independent arthouse cinema.

Cofounded in 2006 by Wen Song and Ziwei Li, two graduates of the Communication University of China in Beijing, FIRST was previously known as the Student DV Film Festival, as the festival’s website explains. Its original name was self-explanatory: it positioned itself as a campus event. But more than a decade since its inception, the festival has established a foothold in the landscape of Chinese independent film culture, despite still being very young.

When it comes to a film festival that shies away from the celebration of leitmotif films — usually feted by mainstream events such as Golden Rooster Awards and Hundred Flowers Awards, FIRST is graced by a self-determining and vigorous demographic.

A magnet for diverse interlocutors of cinematic art — filmmakers, scholars, and cinephiles, the cultural institution is socioculturally self-conscious and articulates the urban underground experiences.

An Outpost of Chinese Indie Films

Anglophone cinephiles, fret not if you are utterly clueless about the festival.

“There has indeed been a disparity between FIRST’s reputation within China over the past several years and the lack of attention it has generated from international media,” Chinese cinema professor Michael Berry, also a jury member of the 16th edition of FIRST, tells RADII.

Geographical disadvantage aside, there are several factors for the festival’s inconspicuousness, explains Berry: First of all, the festival sees a lack of star power compared to China’s more prominent international film festivals (like Shanghai International Film Festival, which has featured such filmmakers as Oliver Stone, Luc Bresson, and Barry Levinson).

Additionally, FIRST doesn’t have a ‘celebrity commissioner’ like Pingyao International Film Festival in Central China’s Shanxi province. Helming the Pingyao-based festival is Sixth Generation filmmaker Jia Zhangke, whose presence “has allowed Pingyao to gain a lot of international attention in just a short time.”

The festival’s core mission is to “discover the debut and early works of filmmakers,” and the films submitted must be among a director’s first three features to qualify for the main competition.

But FIRST’s ‘youthful’ aspect is more dynamic and nuanced than meets the eye. With its proclivity for low-budget productions, auteurism, and avant-garde aesthetics, the film festival interposes itself into the Chinese independent cinema landscape that emerged in the late ’90s with notable auteur filmmakers such as Jia Zhangke, Wang Xiaoshuai, Zhang Yuan, and Lou Ye, who are internationally known as China’s ‘Sixth Generation’ directors.

While ‘independent filmmaking’ connotes independence from Hollywood’s profit-seeking system in the U.S., it carried a slightly different meaning in China at that time: The term broadly applied to filmmakers who bypassed the state studio system and sought private financial sources for funding. Without state permits, they shot films anyway and pivoted to overseas festivals for screening and distribution.

Films by such mavericks were a response to the reconfiguration of social structures and modes of production in the early 1990s. As such, they meditate on individual, plebeian experiences in the context of fast-paced urbanization and globalization (therefore, the group is described as the ‘urban generation’ by some scholars). More often than not, their cameras traverse the private spaces of nomadic urban subjects, namely, postmen (Beijing Bicycle by Wang Xiaoshuai), thieves (Xiao Wu by Jia Zhangke), immigrants (The World by Jia Zhangke), and bohemians (Bumming in Beijing by Wu Wenguang).

Disavowing the intense visuals, well-crafted mise-en-scene, and outstanding camera movements found in Fifth Generation tour de forces, the Sixth Generation advocates the aesthetics of cinema verite, or jishizhuyi (‘on-the-spot realism’). It often upholds unprofessional actors, candid camera movement, and natural lighting.

While it would be reductive to lump the young filmmakers at FIRST with Sixth Generation filmmakers, both parties have striking parallels and deep connections, especially when it comes to covering outlandish subjects, realistic aesthetics, and avant-garde narratives.

At the same time, some Sixth Generation filmmakers, such as Lou Ye and Wu Wenguang, have been previously invited to be jury members at FIRST.

Nonetheless, Berry mentions that the notion of ‘independent Chinese cinema’ has transformed.

“Early on, independent Chinese cinema was basically synonymous with ‘underground’ or even ‘illegal’ film,” Berry explains. “But over the course of the last two decades, that earlier notion of independent cinema has been largely replaced with a version that basically refers to smaller budget productions made outside the main production companies like Bona, Tencent [Pictures], Alibaba [Pictures], Huayi Brothers, etc.”

The Precarity of Indie Film Festivals

The founding of FIRST was contemporaneous with the emergence of cultural institutions that constituted an alternative public space in the early years of the millennium.

Multiple independent film festivals — such as Beijing Independent Film Festival (BIFF, founded in 2006), Yunnan Multiculture Visual Festival (Yunfest, founded in 2003), and China Independent Film Festival (CIFF, founded in 2003) in Nanjing — emerged during an era marked by vast transformation, economic multiplicities, and sociocultural unsettlement following China’s opening-up. They carved out a new visual field and public discourse in China, deterritorializing the mainstream spaces constructed by official media accounts or through leitmotif films.

Be that as it may, most of them were short-lived, as the government pulled the plugs and cracked down on grassroots cultural events that agitated them in one way or another. Yunfest was brought to a close in 2013; one year later, BIFF was suspended by the local authorities, who also confiscated the organizers’ 10-year-old archives.

The most recent termination was CIFF in 2020, with the organizer proclaiming that holding a film festival possessing a genuinely pure spirit of independence is “impossible” on its official WeChat account.

China’s biggest independent film festival forced to suspend operations indefinitely https://t.co/nuG5wCOEWY

— South China Morning Post (@SCMPNews) January 11, 2020

“Many of the ‘independent’ film festivals operating in China today have shifted their focus to global arthouse film and independent cinema in a broader context,” Berry says.

He adds that most, if not all, indie film festivals today are under the clout of local governments, which is “indicative of larger shifts taking place in the Chinese film industry since it came under the umbrella of the Publicity Department of the CCP a few years ago.”

Film Festivals With Clever Monikers

It wasn’t until 2011 that FIRST began to call Xining home. Before it arrived in West China, it was relatively unknown outside of Beijing universities. Proximity to the country’s political heart meant a lack of autonomy in operation, as demonstrated by the interference previously inflicted on BIFF by the local government.

In 2008, FIRST awarded Cao Baoping’s 2006 film Trouble Makers — a film that had been flagged by the State Administration for Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) — with the College Students’ Favorite Film Award, which ruffled some feathers and led to a year-long cancellation of the festival. Following a short stint at a campus in a suburb of Beijing in 2010, it adjourned to Xining the next year and took on the English-language moniker FIRST International Film Festival.

The dissimilarities in the festival’s Chinese and English names — besides the obvious omission of the word ‘youth’ in the English version — hint at more complex dynamics. Therefore, a close reading of the translation unpacks negotiations between the festival organizers and the authorities.

Notably, while the event is labeled a ‘film festival’ in its English title, the Chinese name uses yingzhan (影展), or ‘film exhibition’ in Chinese. This is not the first time a Chinese independent film festival has fobbed off unnecessary burdens by strategic naming: BIFF, Yunfest, and CIFF all had the word zhan (展, ‘exhibition’) instead of jie (节, ‘festival’) in their Chinese titles.

Chris Berry, a renowned scholar in Chinese cinema, highlighted that labeling CIFF as an ‘exhibition’ in its Chinese name helped the organizers dodge state scrutiny: to be registered as a ‘festival’ would necessitate being registered with the state’s top film watchdog, SARFT.

But by using the word ‘festival’ in English, FIRST can align itself with its renowned contemporaries, such as Venice, Cannes, or the more independent-film-oriented Rotterdam. In this sense, it’s no surprise that FIRST’s organizers added ‘international’ in their English title, even though its pool of films is not as nationally or linguistically diverse: To compete in the main selection, films must be mostly dialogued in Chinese languages (Mandarin, Cantonese, and dialects) and with a majority of the cast from Greater China.

Going West, Moving High, Being Local

Relocating to a sociopolitically peripheral area has proven a wise choice: FIRST hasn’t experienced any full-scale interruption by the state, except for the sporadic cancellation of particular film screenings.

Having said that, the festival is now co-organized by the Xining government and the China Film Critics Society, and it is neither entirely immune to the ideological state apparatus nor strict censorship. Xining’s sociopolitical extraneousness is in itself a buffer zone where non-mainstream films are celebrated within a niche yet pervasive community.

Xining is the capital city of Northwest China’s Qinghai province, which borders the Tibet Autonomous Region and harbors six Tibetan autonomous prefectures therein. The province is home to a mix of non-Han ethnicities: Tibetan, Hui (a Muslim ethnoreligious group), and Monguor. Its most notable feature is its eponymous body of water, Qinghai Lake, which is not only China’s biggest lake but also one of the largest salt lakes in the world.

While Xining’s geopolitical status has been elevated in recent years thanks to the Belt and Road Initiative, it remains one of China’s least developed, populated regions. Owing to its elevation of 2,275 meters (7,464 feet), summers in Xining are cooler than elsewhere in the country, earning the city the nickname the ‘Capital of Summer’ and attracting tourists looking to beat the heat.

As mentioned early on, there are parallels to be drawn between Qinghai and the state of Utah, when it comes to weather, geography, and cultural diversity. While Utah first hosted Sundance Film Festival to attract filmmakers to the state and promote independent filmmaking, FIRST’s resettlement in Xining was more like a retreat — a chance to flee from geopolitically and sociopolitically dense regions in China and create an art utopia.

And one can easily argue that FIRST’s relocation has been a success: The annual event is simply enthralling for the younger generation in China, regardless of whether or not they are filmmakers.

This year’s edition, which will be held from July 27 to August 4, saw more than 10,000 individuals (primarily college students) apply to volunteer, despite the fact being selected is extremely difficult: the admission rate is as low as 2.68%. The two volunteers from 2021 that RADII spoke with both confirmed the competitive nature of the selection process, which involves three rounds of interviews.

From a film standpoint, the 2022 festival primarily saw submissions from filmmakers born in or after the 1990s — 70%, to be precise.

The opportunity that FIRST provides to up-and-coming filmmakers is something that Sixth Generation filmmakers likely envy. When cutting their teeth in the movie industry, they had to ship their works to overseas exhibitions without official permits — risking their films never being licensed in China or, worse yet, being banned from making movies altogether.

But now, FIRST facilitates the opportunity for indie filmmakers to share their labors and be recognized by domestic audiences. As Covid disrupted global film festivals in one way or another and discouraged Chinese filmmakers from traveling abroad, FIRST has maintained offline screenings over the past few years and greeted domestic filmmakers and filmgoers alike.

Additionally, it isn’t all about films: While visiting the region, festival-goers often make it a point to attend unaffiliated spinoff events such as indie music performances and tours of the Qinghai Lake — activities that strengthen the festival’s symbiotic relationship with Xining.

Now more than 10 years after being transplanted to the arid city, the festival is thriving and has become one of the world’s most unexpected indie cultural scenes.

“While FIRST may not be generating as many headlines internationally, within China, it has gradually become one of the most respected forums for showcasing independent cinema,” Berry says.

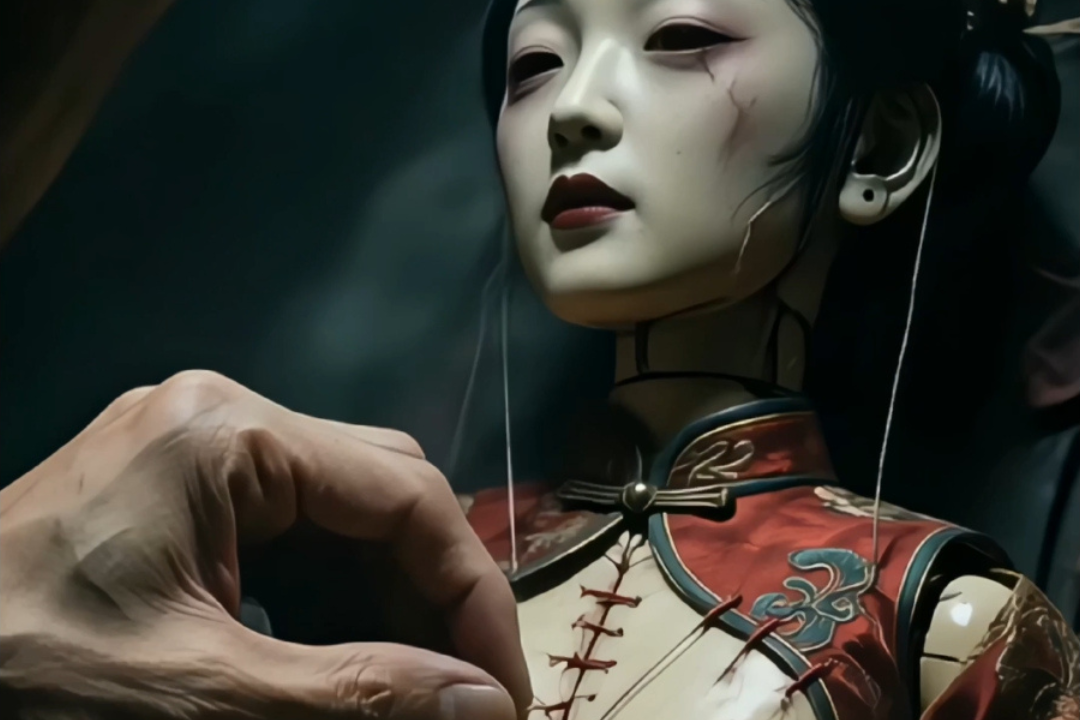

Cover image designed by Haedi Yue, all photos courtesy of the organizer