In 2012, Weibo became awash with news of several branches of KFC supposedly sending “handsome young delivery boys” at the behest of callers looking to spice up the prospect of their otherwise plain order of French fries, chicken and soda. The company quashed rumors in an issued statement denying any compliance with such requests and asked customers to be more considerate towards their employees (i.e. not objectify them).

Flash forward six years and the idea that one called in an order to a restaurant seems quaint, as does the clumsy exchange of cash that mired each interaction. What was already possible with a considerable measure of convenience has been realigned with the contemporary reliance on digital payment systems WeChat and Alipay, but the execution ultimately remains unchanged. I place an order, and it is delivered by hand to my doorstep.

As of late, Chinese gay social media has become obsessed with seemingly innocuous imagery of delivery boys, particularly those belonging to food delivery giants Meituan and Eleme. Identified by their bright yellow (Meituan) or cerulean blue (Eleme) shirts, clunky helmets and obnoxious exhaust-spitting motorbikes, they serve as a new working class fantasy for the subsidized middle class of urban China: country boys just trying to make ends meet in the big city.

One might read this as a subset of the fetishization of uniforms in general, relating to the widespread and mainstream popularity of military uniforms in particular. However, unlike those pictured in military uniform, who appeal to notions of masculine autonomy or dominance, the delivery boy is a figure subject to the whims of others, one of submission and subjugation. This may sound like a bit of a gaff. After all, uniforms in so far as their use within the sexual imagination are intended to be playful, yet the meaning of “delivery boy” is simple. They exist to take an order, not vice versa.

Tianjin-based amateur pornographer TJSGuiSMan (note that that link features some very NSFW images, unless you work in the pornography industry), who manages to operate across a variety of platforms including Twitter, Tumblr, WeChat, and formerly Weibo, has been especially drawn to this imagery, but frankly it has popped up in a number of places and with a frequency rivaling that of Kris Wu’s bus stop advertisements. And it is certainly not exclusive to gay culture or even to China as a simple Google search of “Japan” and “delivery boy” would reveal. Indeed, the delivery boy, like the mechanic or football coach, seems to be one of our most durable sexual fantasies.

And imagination is a healthy and admirable attribute among two consenting adults, but some men in my community — I write as an observer and participant in gay culture here — have started to use Meituan’s app in order to “order” men and have been instructing each other on how to do so.

- Meituan order

The message above describes how to use the 骑手代购 function of Meituan to order a delivery boy, in other words to use the app for prostitution. What we already know as a common occurrence, although vehemently patrolled, on apps like Grindr and Blued, appears more sinister if not entirely absurd within the context of Meituan, suggesting an interaction based entirely on the anonymity of the two actors involved and the real exchange of economic and social power unfolding between them.

It should be noted that neither Meituan nor Eleme are actively encouraging such behavior, incidentally.

My intention is not to inform readers of how to involve themselves with such “play,” but rather to comment on the extreme lack of oversight and protections available to one of the most vulnerable urban groups — even as they seem poised to be replaced by drones. If we are witnessing the beginning stages of the corporatization of prostitution via the digitization of our most basic human desires and needs, those for food and those for love, then we must prepare ourselves for other conversations.

At the end of the day, I would like to believe my neighbor just ordered a dandan mian, that in the midst of this revolutionary period of e-commerce, we have not given up the pretense.

—

You might also like:

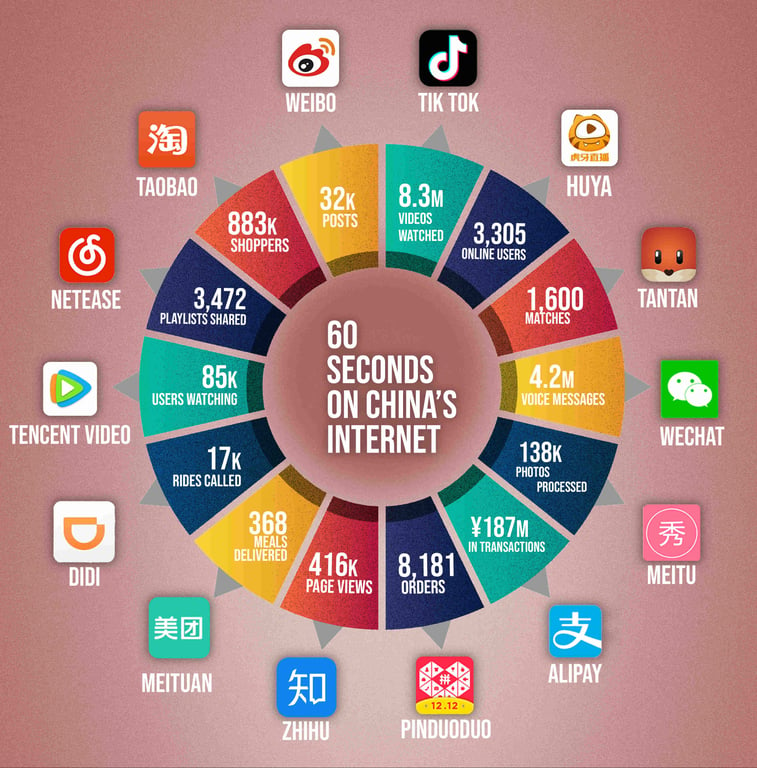

Infographic: Here’s What Happens in One Minute on the Chinese InternetArticle Sep 25, 2018

New Chinese Car Has a Sexy Holographic Anime Girl for a Virtual AssistantArticle Oct 11, 2018

Don’t Get Chinese Internet Slang? Now There’s a Book for ThatArticle Sep 12, 2018