Kung fu movies, as a genre and against all odds, have become one of the most iconic forces in film worldwide.

We say “against all odds”, because we don’t think anyone in the genre’s early days would have predicted global success for such a niche and culturally-specific style of storytelling. Martial arts, Chinese opera, “crosstalk” and comedy performances were blended together into something completely new.

But in retrospect, the rise of kung fu films may have been unavoidable. Kung fu movies are just another vehicle for the same age-old stories people have always told — dressed up differently, and distilled down into easy-to-recognize archetypes. Good versus evil, revenge, justice, and the journey to manhood are themes that transcend cultural boundaries.

Related:

Life with China’s Shaolin Monks: Fact vs. FictionArticle Nov 27, 2018

Life with China’s Shaolin Monks: Fact vs. FictionArticle Nov 27, 2018

But kung fu movies weren’t always international cult classics. It took a long time to build the genre into its current form, and it took more than Bruce Lee, Jet Li, and Jackie Chan. It takes a village to raise a child, and the “child” of kung fu classics was raised by a pantheon of legendary figures — actors, studios, and directors.

Here are seven lesser-known heroes of kung fu cinema. Know them, appreciate them, love them.

1. Shaw Brothers

There’s no better way to kick this piece off than with the Shaw Brothers themselves.

The Shaw Brothers are probably the single most important group in the founding of this particular film genre. As the eldest sibling, Runje Shaw handled the dual jobs of managing their early studio in Shanghai, as well as directing their movies. His younger brothers Runde, Runme, and Run Run handled accounting, distribution, and odd jobs. That was in 1925, when the Shanghai-based studio was still called Tianyi Film Company.

Runje Shaw poses by a camera with cast and crew of “Swordswoman Li Feifei” (source: Baidu)

Runje used to run a classical theater, but made the jump to film after watching colleagues of his achieve early success with the medium. His first movies were immediate hits — 1925’s A Change of Heart made it big at the box office, and Swordswoman Li Feifei, released in the same year, is considered the earliest Chinese martial arts film. Runje had a knack for bringing Chinese culture to the silver screen, from imperial costume dramas to traditional myths.

Right before the Japanese invasion of Shanghai, Tianyi Film Company moved equipment and operations to Hong Kong, and Shaw Brothers Studio was born in earnest. The rest is kind of history — Shaw Brothers became the most iconic name in Chinese or Asian cinema anywhere, and built the identity of the classic “kung fu movie” from the ground up. Thank you Shaw Brothers, for your contributions to the genre.

2. Gordon Liu

With Shaw Brothers Studio up and running, it was only a matter of time before its first superstar was born. Gordon Liu hailed from Guangdong, and studied Hung Gar style kung fu under master Lau Cham. He managed to star in some pretty significant films, but it wasn’t until his signature role as the monk San Te in The 36th Chamber of Shaolin that Liu became a household name.

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin is widely considered to be one of the greatest kung fu films in history, and marked a career turning point for Liu and the film’s directors. It’s the reason Wu-Tang Clan’s debut album was called Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). Admire some of the raw beauty of the film below:

You may also recognize Liu from a totally different franchise: Kill Bill. In Kill Bill Vol. 1, Liu played Johnny Mo, the leader of the Crazy88 Yakuza gang.

Later, in Kill Bill Vol. 2, Liu returned, but in a different role, this time as the infamous kung fu assassin, Master Pai Mei.

The latter was a special role for Liu — Pai Mei is a recurring character throughout Shaw Brothers lore, and Liu has been on the receiving end of some serious Pai Mei beatdowns, in films like Executioners from Shaolin and Fists of the White Lotus.

Gordon Liu left his mark on kung fu cinema — especially through his style and timing in fight choreography — across continents, cultures, and generations.

3. Yuen Woo Ping

Already in this series we’ve talked about directors and actors, now let’s turn the lens onto another instrumental figure — the choreographer.

Yuen was born in Guangzhou, and landed on the movie scene with a splash, nabbing his first director credit on Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow with Jackie Chan. The movie was a hit, and set the tone for Jackie to define his unique style of comedic kung fu. Yuen was the other half of that creative process, and the two recognized their chemistry. They quickly followed Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow with the hugely successful Drunken Master.

Interesting fact about Drunken Master: it features the actor Yuen Siu-Tien as the beggar, who is actually Yuen Woo-Ping’s real life father, an accomplished martial arts star in his own right.

Yuen’s Hollywood debut came unexpectedly, when the Wachowskis reached out to have him work on The Matrix. His dynamic, visual style of action storytelling allowed him to remain as a key figure in the international film scene for years, as he earned credits on The Matrix sequels, as well as Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon and Kill Bill.

Also, it would be remiss not to share this one-of-a-kind piece of Yuen Woo-Ping handiwork, a scene from 1985’s Mismatched Couples, during China’s first wave of hip hop curiosity:

Yuen Woo-Ping is a kung fu choreographer, action director, and a powerful figure in kung fu film in every sense.

4. Sammo Hung

Sammo Hung is a legend, whose hand has touched almost every aspect of modern kung fu cinema.

Sammo Hung was thrust into martial arts performance at a young age. Both his parents worked as costume designers, so he was looked after by his grandfather, a film director, and his grandmother Qian Siying, one of China’s earliest kung fu film stars. When Hung turned nine his grandparents enrolled him in the China Drama Academy, a Peking Opera school in Hong Kong. This would prove to be influential — during his seven years at the academy, Hung became close friends with a younger student named Yuen Lo, who would eventually achieve international fame under the name Jackie Chan.

Sammo Hung and Jackie Chan made their acting debut together in 1962’s Big and Little Wong Tin Bar

At one point in time, Sammo and Jackie performed together in the kung fu group Seven Little Fortunes. Jackie is lovingly called da ge (“big brother”) by Chinese fans; Hung used to have the same nickname, but after Project A, which featured both actors, Hung ascended to da ge da (“biggest brother”).

We talked about how Yuen Woo-Ping is partially responsible for Jackie’s signature style of kung fu/comedy crossover, but Hung had a big role in that too, helping to reimagine the genre towards the late ’70s, as Mandarin-language courtroom epics started to wane in popularity. That was right around the time when Drunken Master came out, making Yuen Lo into Jackie Chan.

Since then, Sammo has shaped basically every part of kung fu film culture in some way or another. Here’s the trailer for 1985’s Mr. Vampire, a seminal work in the jiangshi genre, a subgenre of kung fu vampire films that Hung is credited with inventing.

Look, here’s Sammo Hung fighting Bruce Lee that one time in the opening scene of 1973’s Enter the Dragon:

Sammo Hung has been everywhere and done everything. We salute him.

5. Michelle Yeoh

Michelle Yeoh just oozes perfection. She steals the show in every role she’s played, and unlike some of the other figures on this list, Yeoh doesn’t come from a background in martial arts. But that’s not enough to stop her from becoming the world’s most significant female kung fu star.

Yeoh was born in Malaysia, and actually learned English and Malay before tackling Cantonese (she performed her Mandarin-language lines in Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon phonetically). From a young age it was dance, not martial arts, that drew her attention. She started ballet at the age of four, and at fifteen moved to the UK with her parents to enroll in the Royal Academy of Dance in London. A spinal injury stopped her from achieving her ballet major, and she turned her attention to choreography and other outlets instead.

By 1983, she was already on a totally different wave, winning at the Miss Malaysia Beauty Pageant, and picking up the crown for Malaysia at the Queen of the Pacific beauty pageant in Australia that same year. That led to a turning point for Yeoh in 1984, when she appeared in a Guy Laroche commercial, which you’re about to watch right now:

The spot caught the eye of rising Hong Kong production studio D&B Films, and Yeoh entered the film industry, working with other greats from this list like Sammo Hung and Yuen Woo-Ping. Her films were commercial successes, and her background in dance allowed her to do most of her own stunts.

International recognition came later. She actually retired from acting in 1987 after marrying Dickson Poon, who co-founded D&B Films with Hung. The couple divorced in 1992 and Michelle Yeoh went on to become the superstar we all know and love, because we’ll be damned if a guy called Dickson Poon is going to get in the way of that. Only in the post-Poon era did we get some of Yeoh’s most iconic performances, such as in Tomorrow Never Dies, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, Memoirs of a Geisha, and most recently, as the matriarch in Crazy Rich Asians.

Michelle Yeoh has worn many hats: actor, dancer, beauty queen, conservationist, and martial artist, to name a few. We love Yeoh’s work, and so should you.

6. Golden Harvest

We started this list with the Shaw Brothers. They’re the ones who got the ball rolling in Hong Kong, carving out a real Chinese language film identity for the first time. But, by the end of the ’70s, a new studio had emerged as top dog in Hong Kong. You might recognize this iconic opening sequence:

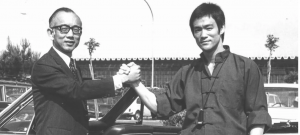

Golden Harvest was founded by Raymond Chow and Leonard Ho, two executives from Shaw Brothers who left the company in 1970 to form their own studio. They took a different approach, working frequently with independent producers rather than keeping everything in-house, and offering actors higher pay and greater creative freedom. There were a few defectors from Shaw Brothers, but Golden Harvest’s biggest win happened in 1971, when they inked a deal with Bruce Lee for The Big Boss. It was Bruce’s first starring role, after he’d turned down the standard contract offered by the Shaws.

Raymond Chow and Bruce Lee

While the Shaw Brothers should be given credit for introducing kung fu movies to overseas audiences, Golden Harvest was the first Hong Kong studio to collaborate directly with Hollywood, producing 1973’s Enter the Dragon as a joint effort with Warner Bros. That was the first English-language kung fu film, and the last film Bruce Lee made before his sudden death.

Since Golden Harvest really picked up speed at the end of the ’70s, they were also just in time to snag a young Jackie Chan, after his popularity exploded in 1978’s Drunken Master. Until rather recently, Golden Harvest had been behind nearly all of Jackie’s films, not to mention padding their portfolio with other A-listers such as Jet Li and Donnie Yen.

If the Shaw Brothers were the ones to first crystallize the kung fu genre, Golden Harvest really took it international, and gave us a roster of enduring superstars in the process.

7. Zhang Yimou

In the ’70s, everyone got bored of cheap flying effects and supernatural camera cuts, catalyzing the switch to a more realistic sense of martial arts action.

Actually, that genre of flying martial arts fantasy has its own name, wuxia, and shouldn’t be confused with the more “ordinary” sort of kung fu flick. Picture Drunken Master, which follows Jackie Chan chasing girls, getting into neighborhood scraps, and trying to dodge his dad’s punishments — that’s a standard kung fu movie. Now picture Hero, with Jet Li running across lakes, and having swordfights in the sky with ancient Chinese assassins — that’s a wuxia movie.

Hero (2003) trailer. Excuse the dated “movie trailer narrator voice”

Wuxia was once all the rage — it spoke directly to the traditions of Chinese culture, and thrilled viewers in the early days of film, back when the visual treat of a moving picture was already enough to grab viewers. But soon enough, audiences stopped being captivated by old-school special effects, and the focus shifted to martial arts films that relied less on fantasy.

This is a lengthy way to get to the point, but here it is: Zhang Yimou changed all that. More than anyone else, he revived the wuxia genre for modern day audiences.

At this point in the wuxia arc, it would be wrong not to mention Ang Lee’s tour de force, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon. The film was nominated for ten Academy Awards, and proved the genre could hit home with an overseas audience. With that in mind, Zhang Yimou directed Hero, targeting an international viewership. Audiences fell in love with the balance of action, romance, and cinematic beauty, all channeled through this exotic medium of Chinese kung fu.

Related:

Is Zhang Yimou’s Remarkable “Shadow” Set to be China’s 2019 Oscars Pick?Article Oct 01, 2018

Is Zhang Yimou’s Remarkable “Shadow” Set to be China’s 2019 Oscars Pick?Article Oct 01, 2018

Hero received sweeping critical praise and a 95% score on Rotten Tomatoes, so it’s not surprising that Zhang continued to push forward with his wuxia renaissance. In 2004, he gave us House of Flying Daggers, which also received over-the-top enthusiasm from critics. Curse of the Golden Flower continued in the same vein in 2006.

Zhang Yimou had a trick up his sleeve for some of those big wins — the action choreography of Ching Siu-Tung.

Ching was brought into the film industry by his father, a Shaw Brothers Studio director, and grew up studying Peking Opera. He trained Northern Style kung fu for seven years and started as an actor, before becoming a renowned director in his own right. Ching directed influential films like A Chinese Ghost Story, which was based on the writings of Qing Dynasty folklorist Pu Songlin and ushered in a trend of occult themes in Hong Kong’s film industry. You can spot his action choreography bolstering Zhang’s most iconic works.

Zhang’s vision defined the tragic beauty and lush visuals of modern wuxia. We thank him for those films, which are all worth watching over and over again.

—

Kung fu movies aren’t just a niche genre of film — they’re a cultural legacy, whose history underscores the histories of the people who made them.

From the Shaw Brothers’ early experiments, to international recognition and Academy Awards, kung fu movies have made their mark on the world. We salute the unsung heroes — actors, directors, choreographers, and studios — who made the genre what it is today.