While it’s often not very meaningful to factor an artist’s influences into a consideration of their own work, the fact that Guangzhou-based illustrator and painter Tony Cheung name-checks Dutch surrealist Hieronymus Bosch and Nobel-winning novelist Mo Yan as his two key inspirations is telling. Bosch’s outlandish paintings and sketches provide an oblique, almost heretical glimpse at the psychological currents flowing beneath the deeply traditional, Catholic culture of the 15th-century Netherlands. Mo’s novels — including his 1986 debut, Red Sorghum, and his most recent, 2009’s Frog — are notable (and notorious) for their “hallucinatory realism,” rendering horrors from China’s recent past in terse, brutal prose.

One can see strands of both at work in Cheung’s frenzied, often grotesque imagery. At first glance, however, his other aesthetic touchstones are easier to identify: his figures, usually young Chinese men and women, look like they’ve been lifted straight from vintage propaganda posters. The explicitly sexual and violent scenarios in which they often find themselves are clear descendants of Shunga and Hentai from across the East China Sea.

But beneath the shock value, the bright palettes, and the highly Instagrammable format that Cheung often prefers, lies a deeper critique of contemporary Chinese society, which the artist believes has been hollowed out by capitalism and technological upheaval.

With a few art books and exhibitions across Europe under his belt, and the newly launched Singularity Festival in Guangzhou taking up much of his time of late, Cheung’s star is rising. Here’s a peek at what this prolific 30-year-old is thinking:

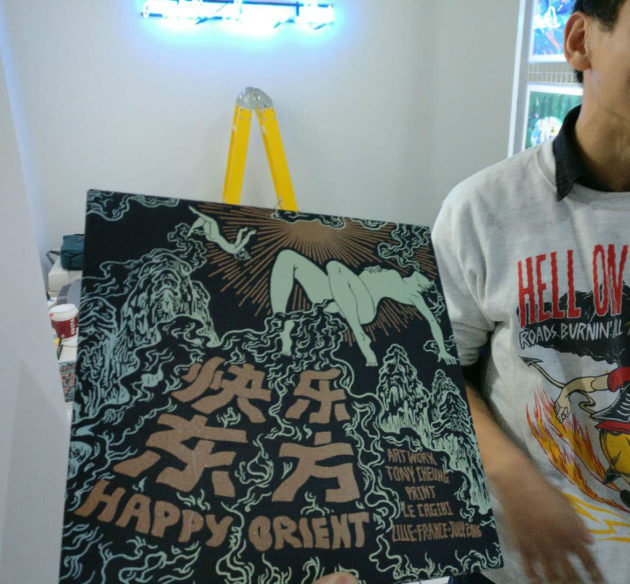

(Photo by Josh Feola)

First some background: who are you? Where are you from originally? How long have you been living in Guangzhou?

My name is Tony Cheung, a freelance illustrator and visual artist based in Guangzhou, China. It’s hard to say where’s my origin. I was born and raised in different places, but all in Guangdong Province. I have been living in Guangzhou for over a decade.

How did you get started as an artist?

My art career started with a book design course assignment while I was in college, in which I drew lots of interesting illustrations with these freaky characters playing around, and then put them altogether into the book. After my graduation I made some merchandise out of those illustrations, like phone cases, postcards and shirts, selling them in the art and design market. The feedback was really good, my works amused and shocked some people.

After I began to take my work seriously, lots of new ideas came out. The turning point was Crack Festival — the biggest underground comics festival in Europe. An Italian journalist found my work in the market and introduced me to Crack. My first experience there in 2013 was totally mind blowing — it was also the first time I realized it’s not important what kind of media you work with, or how famous you are, what matters is passion and pure idealism toward art, as long as it’s critical thinking.

These European artists’ works not only inspired me, but also granted me sense of security to join the big family as an underground artist. The following couple of years, I tried so many different media and subjects, like porcelain, Chinese painting, and acrylic. In 2017, I had my first solo exhibition in Rome. Things are getting better and clearer as my artistry grows.

Your illustrations are often surreal, violent, and sexually explicit. Why do you explore themes such as violence and sexuality in your work?

I think Hieronymus Bosch’s paintings and Mo Yan’s novels influenced me a lot, when it comes to the surreal part of my works. Bosch’s crazy imagination and exquisite technique, and Mo’s disturbing depiction of China’s modern history stimulate my desire to express myself, to draw and paint this way. Furthermore, the common saying about China’s reality being a “magical realistic” existence also drives me to exhibit my understanding about what is happening around us.

Speaking about violence and sex, these are still a big taboo according to the authorities, or even mainstream values, which also lures me to break the limitation. Perhaps playing games with taboo is always fascinating for the young generation. At the same time, for me it seems like the violence part is related to China’s haunting modern history — like what you see in Mo Yan’s work — while the sex part is linked with the present: the chaotic situation after a couple decades of development has successfully hollowed out our spirit, leaving us with endless physical satisfaction. And sex seems like a good metaphor for materialism, our only religion in modern times.

Young women, in particular, receive most of the violence in your art. Why is this? Is there something about gender relations in modern Chinese society that you’re trying to express here?

It seems true, but not totally. There are also males who accept inhuman treatment in my works. Anyway, gender issues are indeed a big part of my art. Using objectified female images is a tactic for me, since in the capitalist system, women being objectified is a huge symbol. As a man living in this abused stereotype of females, I am tired of this situation.

Creating female figures being humiliated, abused, or even worshiped could be a sarcastic rebellion to the gender cliche. But what exists in my work might be more complicated than this. You know, in 1980s China, women becoming a sex object was a big symbol of the society’s opening up, and also a call for more freedom and change. But nowadays this has created another problem, as women are losing their subjectivity in front of the unstoppable capitalist machine.

For example, in my work Kill the slut!, the sexy woman was twice exploited: by the viewer, who is hypothetically male, and by the little girls surrounding her, who represent suppression from the system — authority and tradition. Having and exposing the hyper-sexy body is a rebellious gesture against the power, but sexiness and desire has unfortunately become a trap for de-subjectivity when facing up with the gaze from men, or capitalism.

I put these women and men into different sex-related scenarios — their games not only show the tension between sexes, but also tension between the ruler and the ruled, the past and the present, liberty and repression.

Your depictions of Chinese youth look like they are inspired by posters from the 1960s, but the darker subject matter seems to come from other sources, like the more extreme end of Japanese manga. What are some of your artistic influences?

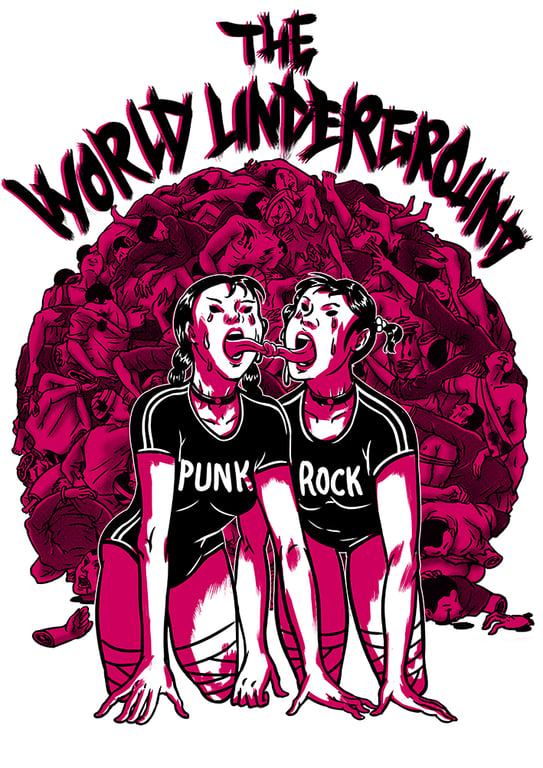

Yes, you’re right. Revolutionary-era posters did inspire me a lot, especially in my last group of works, but after a few years of exploration, I grew tired of this poster style, and started changing to other visual resources, like Japanese horror manga, Chinese figure painting, Shunga [Japanese erotic art], extreme cult movie posters… These have become my new source of inspiration.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BcwYdkBl32n/?taken-by=tungningcheung

Some of your recent works feature Western brands like Coca-Cola and Starbucks inserted into an industrial or bureaucratic Chinese setting. In your opinion, what is the appropriate relationship between art, brands, and corporations? Do you attempt to critique this relationship in your work?

I am quite a cynical person, even though I’m 30 years-old — not common in China nowadays. Discontentment about the reality of our society has become a big motivation of my compositions. In terms of the Western brands, these symbols aren’t simply showing my opposition against or disgust towards Western influence, they’re natural and objective presentations of how society looks in my eyes.

This huge nation and its people are struggling so hard to find the balance between modernization — shown as Westernization — and its heavy, haunting tradition. And this dystopian future imagination, juxtaposing industrialized images and traditional objects, along with enthusiastic students and disturbing violence, really fascinates me. It’s obvious that I am critical about where we’re heading — industrialization and the revival of our nationhood’s fairy tale — but hesitation and self-doubt also come along all the way.

There is no appropriate relationship between art, brands and corporations for me. In this post-modern world, anything can be art, and not art. Commercial illustrations can possibly be more artistically valuable than the expensive oil paintings in the museum. The judgement toward art should rely on the individual, and time. But as the composer, I think sustaining an independent and critical way of thinking is the crucial thing.

Speaking of that, what do you do to make money? How do you balance your time between commercial work, and purely artistic pursuits?

I make less money with my art. Sometimes I draw for bands and get paid, and people may buy my works from social media. My so-called purely artistic pursuit has put me into an awkward situation: it’s hard to earn a good living through independent composition. This is exactly why my friends and I are running a platform called Singularity Plan, attempting to help artists who sustain an independent spirit and look for opportunities.

Besides that, I am attending more art festivals and exhibitions in Europe, where my work sells better. [laughs]

Another theme that’s popped up in your work recently is Virtual Reality. What interests you about VR? How do you think technology is changing how we experience art and/or reality?

Interesting questions! There are arguments about technology when it comes to the issue of art. The combination of composition and technology seems to be a trend, but still controversial for some people who think art with texture is what we should admire. For me, there’s no doubt that we will be embraced and surrounded by technology like VR — there’s no way to escape.

Speaking about art, it’s for sure that ways of seeing for our next generation will be changed. And it’s optimistic to imagine that even kids from the poorest regions can attend the Louvre museum, like any Parisian, with VR equipment. I am using Photoshop to draw and paint all the time, and digital art can show the same power compared to other techniques, if the content is strong enough.

On the other hand, there will definitely be another trend of composers going backwards in our art and craftsmanship tradition, searching for possibilities. Aesthetic form and content are equally important for art, no matter what age we live in.

I first became aware of your work through a few collaborations you did with record labels and bands, such as Genjing Records and Round Eye. Are you a big music fan? What kind of music do you like? What kind of music do you think best matches your visual style?

Yeah! Big fan of music. That’s why I feel so honored to be part of it. I know nothing about instruments and music theory, which doesn’t affect my passion about it. I like all kinds — from Classical to pop, rock to folk. Music and audio books are always my companions when I draw and paint.

I think death metal, punk, indie pop, and even noise music could be a nice match for my style. Because all the kids I draw have these freaky, energetic faces. Whether they’re smiling or crying, they need to be fed with this spiritual poison — music.

You’ve recently been involved in organizing a festival in Guangzhou. Can you talk about that? What is it all about?

We organized an underground art festival, the Singularity Fest in Guangzhou, last September. It turned out to be quite a successful event. Over 60 artists and groups joined us, and thousands of people came. The selling point was, well, giving us confidence to build this platform for underground art, trading and promoting. That’s why we started our own gallery and website, aiming to help the growth of underground culture in China. There are lots of possibilities and vitality in this territory, in spite of all kinds of limitations.

What else have you been working on lately? Anything else you want to add?

I am working on a new collection named Chemical Happiness. Part of this huge, long painting will be featured and exhibited in an outdoor festival in Rome this April.

—

Tony adds: “If you wanna see more works of mine, my Instagram account is: tungningcheung. I am open for all collaborations. Thanks a lot.” You can also check out the work of Singularity Plan, the arts platform and festival Tony co-founded last year, right here.

All illustrations courtesy Tony Cheung