Colloquially called the Berlinale, the Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) has certainly been unconventional — arguably more than usual since it was founded in 1951 — over the past two years. Although the 2020 ceremony dodged the first lockdown in Germany, the pandemic disrupted its traditional live audience screenings in 2021 and this year. (While in-person screenings were held in 2022, attendance was limited, and anti-Covid procedures were in place.)

Meanwhile, the 2021 and 2022 festivals saw the Berlinale revolutionizing the traditional Best Actor and Best Actress prizes: Both have been replaced with non-binary titles, namely ‘Best Leading Performance’ and ‘Best Supporting Performance.’

In 2022, both categories were awarded to actresses, therefore continuing a trend set by the Cannes and Venice film festivals, two events that — along with the Berlinale — comprise Europe’s ‘Big Three.’ Over the past two years, the trio of film festivals also bestowed young female directors — Carla Simón at Berlinale 2022; Julia Ducournau at Cannes 2021; and Audrey Diwan at Venice 2021 — with the Best Film award.

Juried by M. Night Shyamalan (Berlinale president), Zimbabwean filmmaker and writer Tsitsi Dangarembga, and Japanese filmmaker Ryûsuke Hamaguchi, among others, for the main competition, this year’s Berlinale had a diverse body — with wide-ranging tastes. Renowned Chinese documentary filmmaker Bing Wang was one of the jury members for the Berlin Documentary Award.

Although Sinophone filmmakers were once again absent from this year’s festival as a result of the ongoing Covid pandemic, many Europe-based Chinese cinephiles — myself included — traveled to Berlin from February 10-20 to report on the Chinese-language films premiering there. Two were submissions from the Chinese mainland and one short film (Gong Ji directed by Myo Aung) from the island of Taiwan.

Below, I share my thoughts on Li Ruijun’s Return to Dust and Zheng Lu Xinyuan’s Jet Lag.

Return to Dust

The 131-minute film follows two marginalized individuals who have been cast off by their own families and communities. Set a decade ago in Northwest China, specifically the countryside of Gansu province, the protagonists are in the process of getting into an arranged marriage and making a life together.

There are neither vows nor celebrations for the destitute pair, just monotonous yet touching routines such as building a house, fetching hot water and caring for one another as they try to live with dignity.

Return to Dust, Director Li Ruijun’s fifth feature, was the only Chinese film in the Berlinale’s main arena this year. The 39-year-old director had already gained international recognition by participating in Cannes Film Festival’s Un Certain Regard category and the Berlinale’s Generation section in previous years.

As none of the film crew could attend the festival, the director and main actors recorded short interviews for a prescreening. Hai Qin, the only professional actress in the film, is a household name in China, having starred in many movies and TV series since the early 2000s. Conversely, lead actor Wu Renlin, who plays the husband in this film, is a local farmer from rural Gansu.

Return to Dust was shot close to where the director grew up, and nearly all the folks who appear in the film are non-professional actors from his hometown, including his own relatives.

“I’m so glad that you are able to come to this film. In this movie, I played a farmer. But in real life, I’m also a farmer. If I had to choose between farming and acting, I’d say I’m better at farming. I treated my role in the film the way I treat the crops on my land: I take care of them and grow with them. I sincerely hope that you all enjoy this film.”

— Wu Renlin in a prerecorded video shown at Berlinale 2022

Li’s quest in highlighting the underrepresented peasant community in rural China aims to truthfully reconstruct ideas of rural life with poetic framing, gorgeous cinematography, and a heartfelt score by prolific Iranian pianist and composer Peyman Yazdanian.

As a result, the harsh conditions of daily life in Northwest China can almost be viewed as idyllic. As Li remarked in the director’s statement before the screening, “Give your fate back to time and land and just wait naturally. The harvest also comes naturally.”

Lead actor Wu Renlin and director Li Ruijun

The film’s visuals and plot may remind some of ‘fifth-generation’ Chinese directors. This generation was born between the 1980s and early ’90s and rose to the international stage with their trademark visual elements revolving around the land and soil. Some well-known names include Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang, and Zhang Yimou, all of whom attended film school after the Cultural Revolution and gained international recognition as the ‘Big Three.’

Return to Dust is indeed down-to-earth while also providing perspective on the dignity of man, even among those who’ve been humiliated and hurt. It also portrays the realistic aesthetics of labor, which are rarely found in Chinese films these days, and the natural environment, thereby emotionally linking us to China’s disappearing landscapes.

Even if one does not understand the social undertones of the story, the viewer is still able to grasp its essence. Thus, the film can be viewed as an unhurried and tearful elegy to humanity. Perhaps this is how Return to Dust resonated with European film critics: Its depiction of an idyllic pastoral landscape away from the hustle and bustle of city life — and a minority’s silent attempt at the pursuit of happiness — harkens back to simpler times.

Many viewers and critics praised Return to Dust, calling it one of the best films at Berlinale 2022, and several European distributors quickly picked up the title after its world premiere at the festival.

Jet Lag

A personal-essay documentary by Millennial filmmaker Zheng Lu Xinyuan, Jet Lag premiered at Berlinale’s Forum, a section independently curated and organized by Arsenal — Institute for Film and Video Art.

The Hangzhou-based filmmaker had already made some noise in both Chinese and international film festivals, from being awarded Best Artistic Originality at FIRST International Film Festival in the city of Xining to winning the Tiger Award at IFFR Rotterdam for The Cloud in Her Room two years ago.

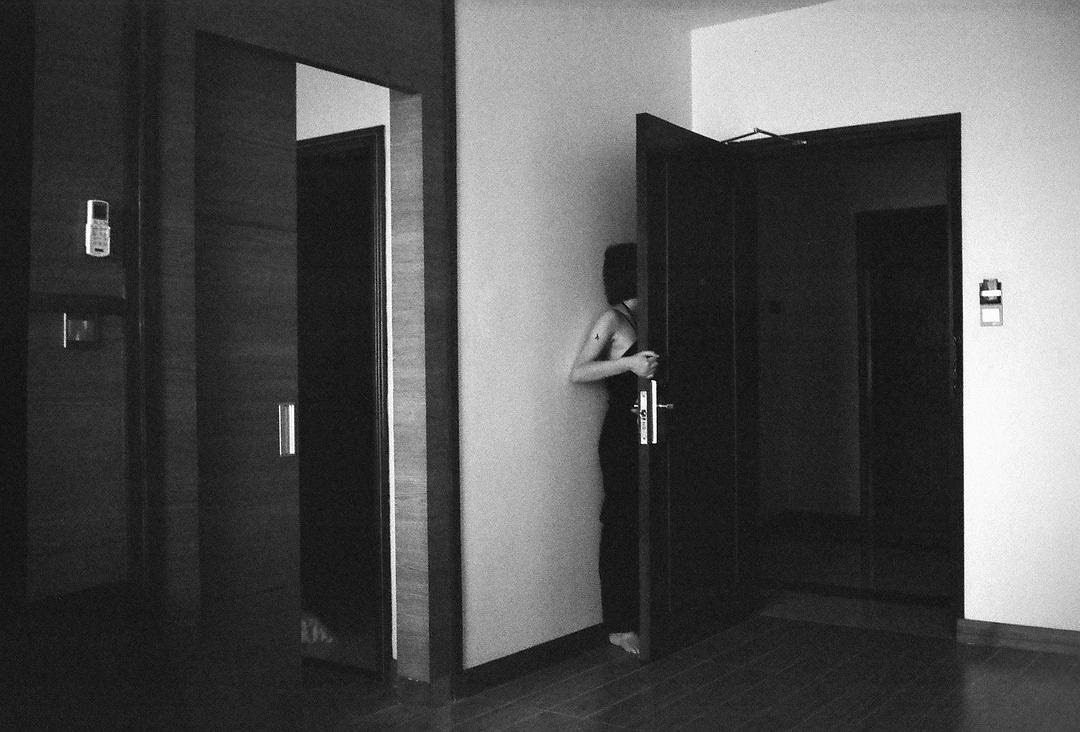

A continuance of Zhang’s black and white visual aesthetic, Jet Lag is structured as a travelogue, which follows the filmmaker’s stream of thoughts without a clear narrative. Two parallel storylines slowly unfold: An inquiry into a family mystery intercut with her life during quarantine.

The first revolves around an overdue family trip to Myanmar. The family seeks to uncover the truth behind the disappearance of Zheng’s deceased great-grandfather, who immigrated to Myanmar to become a Buddhist monk but never returned to China.

This part of the film, mostly shot on a camcorder, pieces together their ancestor’s other life in a foreign land. Later, the filmmaker returns to China with her partner at the height of the pandemic and both are made to quarantine separately.

Film stills from Jet Lag

In contrast to the beautifully shot fragments of family life, the filmmaker’s journey back to China is filled with solitary and self-reflective prose. Zheng excels at tackling heavy topics with sensitivity and delicacy, including sexuality, politics in Myanmar, and paternal absence. The seemingly unrelated themes prove to be interconnected as the story progresses.

Spoiler alert: The film ends with a funny scene of the whole family learning English together — the director’s way of exploring language, communication and intimacy. While the family shies away from expressing emotions in their mother tongue, it seems easier for them to speak sincerely in a different language.

By the film’s conclusion, it’s clear that Jet Lag is a courageous attempt at exploring scattered memories and emotions.

Ostensibly a European production, the film’s international sales go towards Beijing-based company Radiance Films. Jet Lag will undoubtedly receive international attention, as Radiance has also co-produced acclaimed arthouse films such as Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria (2021) and Chinese director Han Shuai’s debut film Summer Blur (2020).

You might also like:

100 Films to Understand China: Documentaries10 films covering vibrant subcultures, the legacy of “Opening Up,” the struggle of migrant workers, and other fragments of life in ChinaArticle Feb 01, 2021

100 Films to Understand China: Documentaries10 films covering vibrant subcultures, the legacy of “Opening Up,” the struggle of migrant workers, and other fragments of life in ChinaArticle Feb 01, 2021

Cover image designed by Haedi Yue; all other images via Douban