During the first wave of kung fu-mania, writer Steve Engelhart and illustrator and judo enthusiast Jim Starlin created the character Shang-Chi for Marvel.

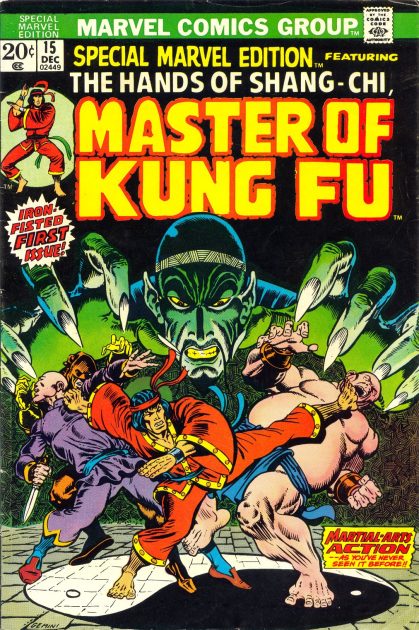

It was 1972, and Bruce Lee was a household name, while movies by Hong Kong legends the Shaw Brothers played regularly at grindhouses around the US. The Marvel martial artist made his first appearance in 1973 in Special Marvel Edition issue 15, and after just two issues of Master of Kungfu, he became a sensation.

Culturally, however, Shang-Chi’s story and origins are weighed down by some highly problematic baggage.

The first issue is that Shang-Chi is a Chinese character concocted by a couple of white creatives. This led to storylines that assert him as the son of Fu Manchu, English literature’s most infamous ‘Yellow-Peril’ racist stereotype. Created by Sax Rohmer in 1912 and propagated via 13 novels, the villain made the jump to the silver screen in Don Sharp’s The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), starring Hammer Horror stalwart Christopher Lee in yellowface and a drooping mustache.

Christopher Lee in yellowface in The Face of Fu Manchu. Image via IMDb

Having already capitalized on Sinophobia with the characters Yellow Claw and the Mandarin, Marvel apparently had no qualms about importing Fu Manchu’s opponents from the novel, Sir Denis Nayland Smith and James Petrie, and allowing them to use the same kind of xenophobic, anti-Chinese language that was seen in Rohmer’s books. To add insult to injury, Shang-Chi is shown to be sympathizing with them.

The conceptual and visual details are also littered with mistakes. Despite Engelhart’s declared interest in Eastern philosophy, he still refers to teachers in China by the Japanese sensei rather than the Chinese word for master, shifu. Additionally, made-up characters written in stereotypical Chop-Suey font punctuate the fight scenes and serve little purpose.

A Hero of the Times

The publication of Shang-Chi began in an era when China was still a closed country.

The character was created just two years after the meeting between Glenn Cowan and Zhuang Zedong at the 31st World Table Tennis Championship, which initiated the era of ‘Ping Pong Diplomacy.’ Before that, there had been virtually no exchange between the two nations since the Korean War, and in the minds of most Americans at the time, China was probably everything their country stood against.

Shang-Chi remained the bargain basement Bruce Lee of the Marvel universe for most of the 1970s and 1980s, gradually fading into the background as new fads came into fashion.

Special Marvel Edition, issue 15, 1973

By the 1990s, however, China had reopened to the world, encouraging economic and cultural exchange. The decade also saw the beginning of a cultural shift in the West towards social, environmental and ethical awareness, and an openness to multiculturalism. China was no longer physically or culturally out of reach, and fans were being inspired by a new generation of kung fu films that reached them on home video, late-night cable, and DVDs.

With New Wave Wuxia Pian films building up momentum for Wuxia to finally break into the mainstream in 2001, Shang-Chi got a total revamp. From his assassin and spy beginnings, he was transformed into a fully-fledged hero.

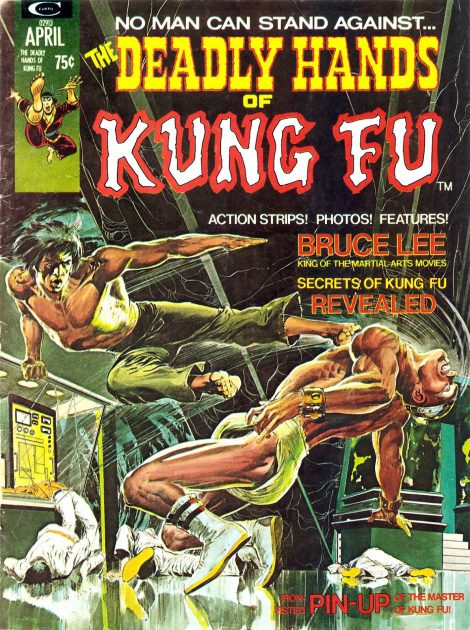

Retiring from his M16 role in The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu (1974-77), Shang-Chi turned away from the crowd, in true hermit master fashion, to spend his days in contemplation, surrounded by nature. However, his peaceful days would not last, as Marvel made extensive use of the Master of Kung Fu by bringing him out of seclusion and into their major story arcs and crossovers.

The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, issue 1

With his kickass fighting skills, keen sense of justice, and Eastern wisdom that came in handy during emotionally difficult moments, Shang-Chi made the perfect support ally for any group of superheroes on a quest. He has fought as part of groups like the Marvel Knights, Heroes for Hire, and the Avengers. He has defeated dragons, competed with immortals in the martial arts tournaments of K’un-Lun, and even faced off against the mad titan, Thanos himself.

Perhaps realizing that the Fu Manchu association would no longer be acceptable, Shang-Chi’s problematic father was retconned, transforming into a deceased crime lord, whose nefarious underworld empire is mentioned, before later morphing into the much less offensive-sounding — but equally shadowy — Zheng Zu (Secret Avengers, 2010).

A Hero For The 21st Century

The comics of the 1990s and 2000s made reasonable attempts to represent Shang-Chi more appropriately by placing him in the Far East and referencing Eastern philosophies. In trying to do more, though, the creative teams demonstrated a gaping lack of skill in artistic depictions of the East, language references, and culturally sensitive characterizations.

The X-Men series Games of Deceit and Death (1997), Wolverine: First Class (2008) and Shadowland: Spiderman (2010) all have glaring examples of this, depicting anachronistic rickshaws, using nonsense Chinese words, and putting ‘fortune cookie platitudes’ in our hero’s mouth.

These gaps could have been filled by writers and artists of East Asian heritage. Still, at Marvel, they were few and far between, with hardly any working on Shang-Chi comics, apart from occasional pencillers such as Alvin Lee (Heroes for Hire), Jimmy Cheung (Infinity), and Tan Eng Huat (The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, 2014).

Comic book writer and artist Philip Tan. Image via Wikimedia

It has only been in the past decade that series such as The Protectors (2017, Greg Pak, Mahmud Asrar) and New Agents of Atlas (2019, Greg Pak, Gang Hyuk Lim, Federico Blee) have provided a rostrum for East Asian creators to forge superheroes out of their heritage.

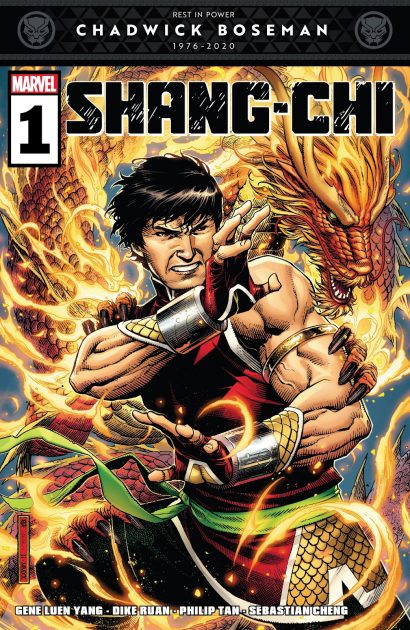

After 40-plus years, Gene Luen Yang, Dike Ruan, Philip Tan, and Sebastian Cheng were finally able to reboot Shang-Chi into a new series of his own within the central Marvel universe.

Shang-Chi (2020) draws from some interesting strands of Marvel’s multiverses and creates a more rounded hero. Yang has Shang-Chi working in a bakery in Chinatown, where he is tracked down by descendants of the organization founded by his late father.

Also included in this new series, the Five Weapons Society is an informed adaptation of the secret societies and sects from Chinese history, most common during the Qing Dynasty, when civil administration and civilian safety crumbled under governmental corruption and colonial machinations. These clans had strict codes of conduct and practiced their own kung fu styles, which could be seen as early modern Chinese superhero prototypes.

Shang-Chi (2020), issue 1

From mountain retreats to high-tech floating bases, from altars to the manifestation of Qi-based powers, the art of Ruan, Cheng, and Tan is a joy to see. They have clearly taken cues from classic Hong Kong horror films and made their mark in the evolution of jiangshi (僵尸, a traditional Chinese undead monster) lore.

Apart from this more sophisticated world-building, parodies of hackneyed Shang-Chi tropes, as well as intelligent social and cultural characterizations, make the story engaging on so many different levels.

This is not a history of Shang-Chi per se, but rather the key developments in his representation in comic book form with added cultural context.

The timeline of Shang-Chi does not end here, though, and the character is set to materialize in yet another alternate Marvel reality, the MCU, in the highly anticipated Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings. The film will hopefully answer some questions that have remained unanswered (and possibly unasked) since the first Iron Man film, when the Ten Rings were first mentioned.

A Hero for the MCU

From the trailer, the film itself looks promising in terms of cultural representation. The Eastern-inspired concept art is impressive, as is the inclusion of ancient mythical beasts (like suanni 狻猊 and Dijiang 帝江).

Wenwu’s (another renaming of Shang-Chi’s father) banner, designed in the style of a traditional shengqi, bears his insignia — a pair of the Mandarin’s weapons, surrounded by supporting symbols held in 10 rings. The characters for ‘Might, Strength, Majesty, Heroicism, Power’ can all be seen, whilst its distinct black color has led some to speculate that he might be a version of Qinshihuang, China’s first emperor.

Scenes showing the otherworldly surroundings of Wenwu’s base and the scale of his private army suggest it could either be located at his China retreat, as per the first comics and the 2020 reboot, or in the celestial city of K’un-Lun, as per Shang-Chi’s alternate life in Secret Wars (Battleworlds: Master of Kungfu, 2015).

Tony Chiu-Wai Leung stars as Shang-Chi’s father in the upcoming Marvel Studio’s film. Image via IMDb

The film has been careful to remove the glaring cultural appropriations, changing the ludicrous dragon name — Fin Fang Foom — to the Great Protector (as confirmed by the tie-in LEGO set), and giving Shang-Chi’s father (who is the true MCU’s the Mandarin) a Chinese name. However, some Chinese fans see it as a tactic to obfuscate the character’s ‘Yellow Peril’ associations rather than remove them.

Having Shang-Chi confront his father, his sworn enemy in the comic universe for decades, actually highlights one of the biggest problems Shang-Chi has as a Chinese character. His estrangement from his father, which was initially necessary to balance his connection to Fu Manchu, now becomes one of the most terrible taboos that a Chinese person could commit.

To make matters worse, it is still tinged with those Sinophobic undertones: He only becomes a hero once he has eschewed his Chinese heritage. It would have been more understandable had Shang-Chi continued to be of mixed race, as he was initially created to be, but one’s cultural ‘otherness’ is always emphasized, even if it’s only part of who you are.

An Americanized Shang-Chi opposing his father and rejecting his heritage could do wonders for the domestic market, but how will it fly in the world’s biggest cinema-going market, China?

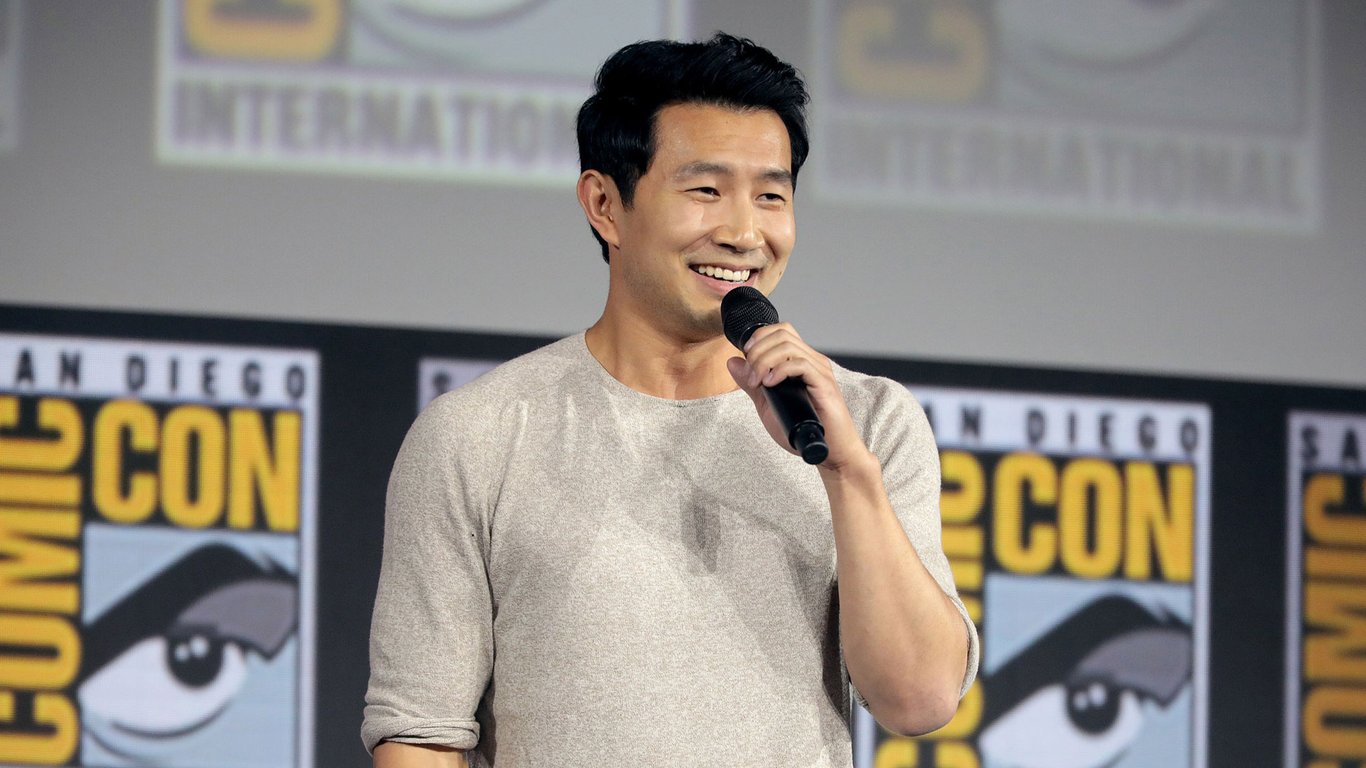

Simu Liu as the titular character in Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings. Image via IMDb

Over the last 20 years, the MCU has become an entity of its own, more accessible than the comics and significantly separated from the silliness of previous entries into the superhero movie genre.

In this ‘phase’ of the cinematic universe, the studio appears to be stretching its wings. Black Widow was a spy film, the second Doctor Strange looks like a horror movie, and it’s clear what genre Ten Rings will be. This hero’s development has always come hand in hand with kung fu cinema.

Apart from the high-octane fight sequences, which look like they’ll pay tribute to slick, comedic action flicks like Kung Fu Hustle and Rush Hour, Western comic fans can look forward to meeting new characters, like Razor Fist and Shi-Hua.

There will also be an appearance from Doctor Strange’s assistant, Wong. (The creators of Shang-Chi had actually intended his comics to be a companion piece to Doctor Strange, but ironically, the intended roles are reversed here.)

Tony Chiu-Wai Leung and Simu Liu in Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings. Image via IMDb

The prize for the martial arts contest in the movie is said to be the highly coveted Ten Rings, an award that is likely to attract heroes as well as villains, with speculated cameos from the wider Marvel universe, including Baron Mordo, Omega Red, and Batroc the Leaper, whom we last saw in Disney+’s Falcon and The Winter Soldier.

We will see the experience through the eyes of Shang-Chi, a Chinese immigrant directly tied to the action, as well as an ABC viewpoint through his friend Katy (played by Chinese-Korean actress Awkwafina).

Due to the pandemic and the stack of Marvel projects that have piled up, Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings is now slated for a September release. It will be followed quickly by Chloe Zhao’s The Eternals and could very well set up elements for that story in the post-credits, if not through cameos in the film.

Marvel’s main timeline has had both the Eternals and the mystic power of the Mandarin stemming from space, which is fine for Jack Kirby’s psychedelic space opera but does not do for a pantheon based on real-world mysticism and combat mastery.

Related:

Simu Liu’s Journey from Failed Accountant to Marvel’s Shang-ChiThe first actor of Asian descent to lead a film for Marvel Studios, he plays the titular role in “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings”Article Aug 25, 2021

Simu Liu’s Journey from Failed Accountant to Marvel’s Shang-ChiThe first actor of Asian descent to lead a film for Marvel Studios, he plays the titular role in “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings”Article Aug 25, 2021

Shang-Chi has no mutant powers, alien augmentations, or technological gadgets. His kung fu skills alone have been more than a match for the countless villains he has fought and defeated and countless friends and allies he has helped and trained. Over half a century of development has amply reflected Shang-Chi’s dynamism and resilience.

After contemplating the I-Ching, his creators named him Shang-Chi (shang qi 尚气), the rising and advancing spirit. With their unwavering belief in their new hero, they produced a sensation.

Their ‘rising spirit’ has overcome the problematic origins he was given and flourished as an incredibly unique and powerful hero. Shang-Chi can help advance Marvel towards a more diverse and representative universe and hopefully become a tool against Sinophobia, which is, sadly, as prevalent today as it was in the time of Sax Rohmer and Fu Manchu.

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings is set to be released in North American theaters on September 3, 2021.