Stating the fact that Beijing is a city in permanent flux might sound trite to the observer who’s already familiar with the Chinese capital’s ever-changing scene, prey to multiple official plans, initiatives, and never-ending, larger-than-life political and economic agendas. However, it’s a condition that for many local members of multiple smaller, sub-cultural scenes can’t be stressed enough, regardless of what the effects such impermanence mean for them. That situation also extends to the institutions and independent actors that constitute the local art landscape.

Inspired by the modus operandi of Beijing’s urban context and its effect on the local art ecology, the Independent Art Spaces (IAS) festival has throughout its three previous editions gathered under its ranks a militia-like troupe of participants. By means of its thoughtful program, the festival attempts to understand what it means to be an independent space in China, while encouraging knowledge exchange about the ways in which such spaces can thrive despite the struggles they might undergo given the nature of their work, and the scarcity of the resources available.

After taking 2018 off, Independent Art Spaces’ just-launched 2019 edition marks a significant change in terms of format, and carries with it a good deal of hope for what’s yet to come for the local independent art scene in Beijing. It brings under its wings 24 local spaces and 10 international spaces, a much larger number than the previous three editions.

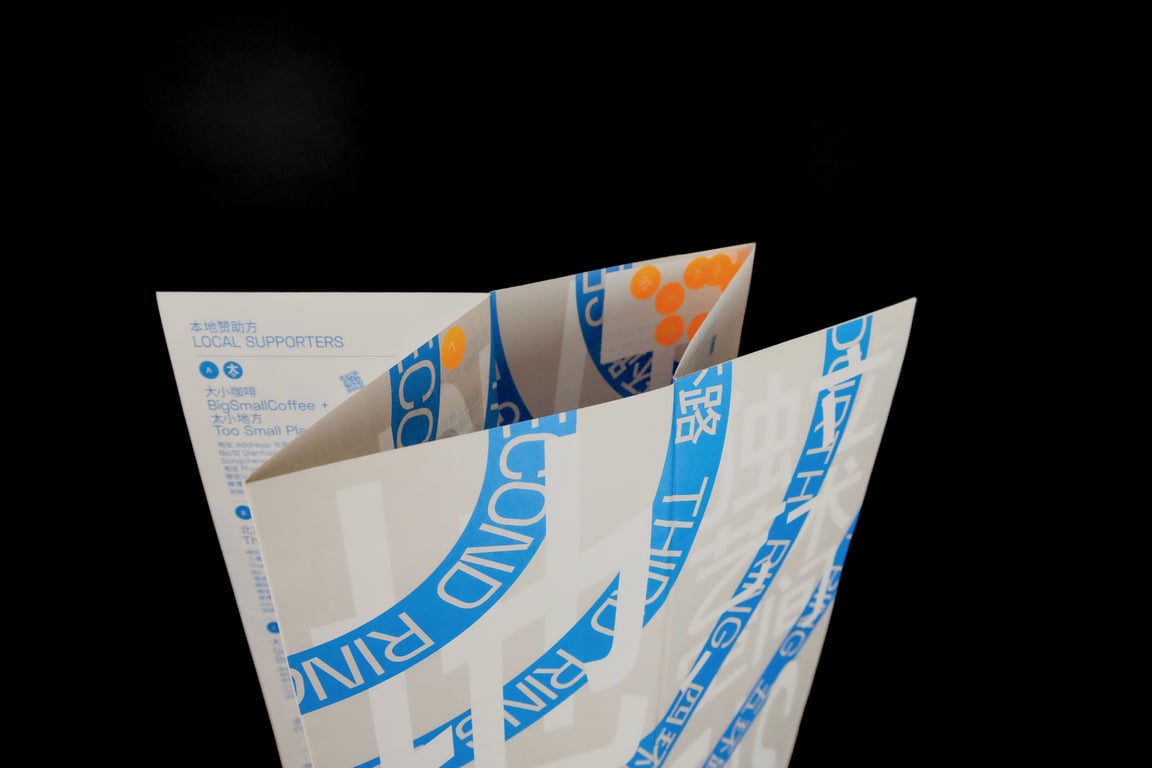

Independent Art Spaces 2019 map

It’s tricky to neatly define what constitutes an “independent art space,” say Anna Eschbach and Antonie Angerer, the brains behind Beijing residency and gallery I: project space and co-founders of the festival. The term encompasses a diverse array of spaces that might differ in terms of financial model, size, or in the way they’re run. There is, however, a common denominator between “the way they create programs and content,” Eschbach and Angerer tell RADII. A distinct way of curating and creating content is largely based on the type of structure they sustain, and in the case of independent spaces making up the festival’s program, “smaller teams that can make decisions promptly based on pressing issues taking place” can create a unique environment as a result of a sustained interest in a particular practice, project or concept.

In contrast to the more hierarchical system that permeates the decision-making in larger art institutions, these spaces’ approaches tend to be hands-on, in part thanks to being either run by or in close collaboration with artists who’ve taken more agency in the way they want to shape and socialize their practice. The IAS festival is therefore a statement of the necessity to establish local and international networks to tackle the multitude of challenges that such spaces might encounter while carrying out their mission.

The IAS 2019 opening event at aotu studio

“Generally, we think the festival has two distinct aims,” say Angerer and Eschbach. “On the one hand, it was about connecting the scene and making the scene visible… [That means] creating a bond of solidarity between the spaces through knowledge exchange, and thus managing to become stronger as a scene. The second part, on the other hand was about making the spaces and their program accessible for the public.”

Just like Beijing, the city in which it takes place, IAS has become whatever it needs to be in order to potentiate its scope and impact within the local network of participating spaces. That’s the reason why, after consciously revising what the spaces under its aegis really needed, they’ve come back with a program fully tailored to tackle as many practical questions in terms of running independent spaces, along with other, larger questions regarding discourse, tools and practices.

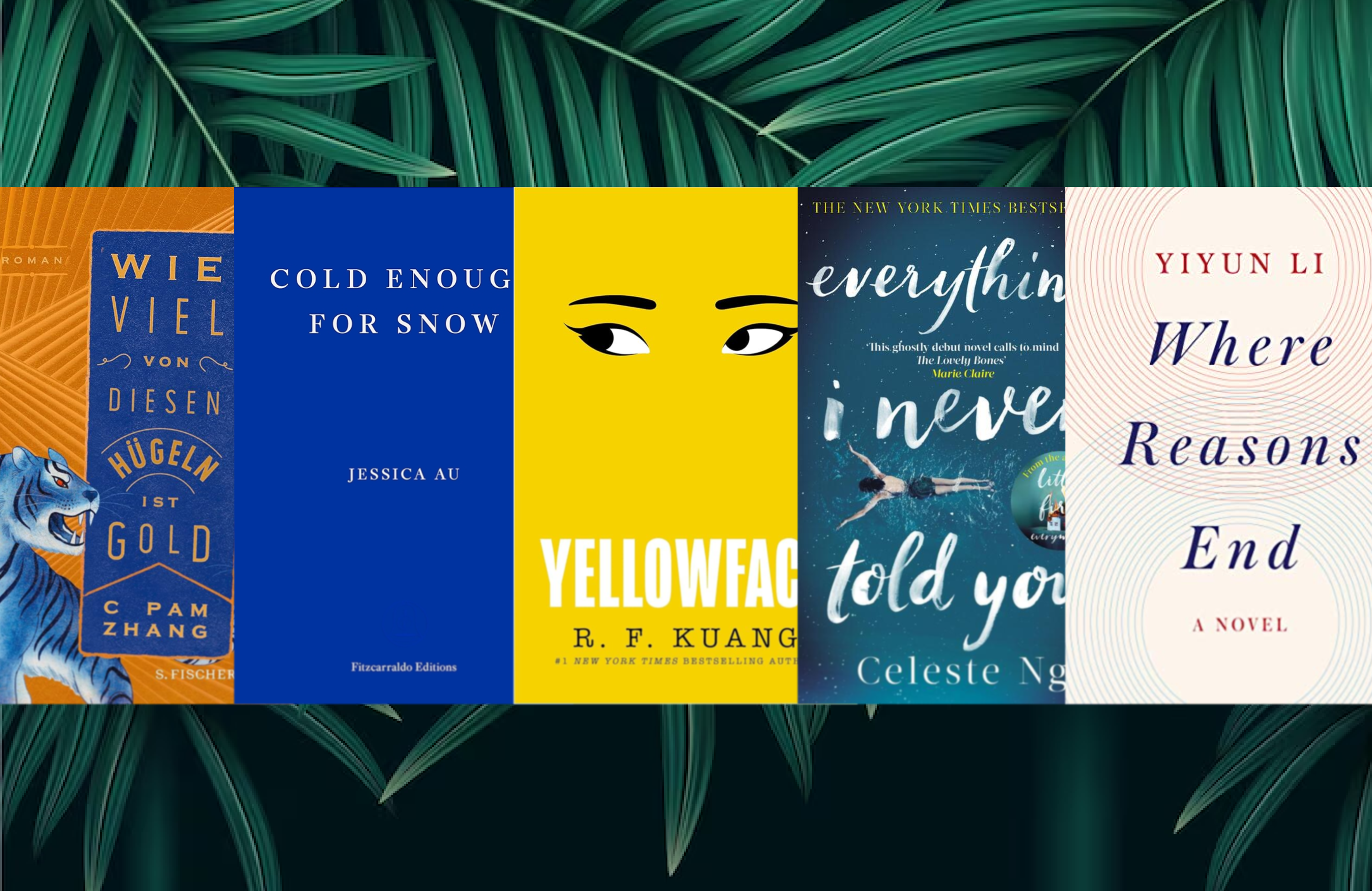

This year’s IAS edition is densely concentrated in two areas that the curators of the festival consider especially relevant: a comprehensive map/directory of the currently existing spaces, with an insightful review of their practice(s); and a series of workshops on what they deem could help spaces surf the waves of the various internal and external adversities they might encounter while trying to fulfill their goals.

The IAS 2019 opening event at aotu studio

Exhibitions will not necessarily be the main aspect of IAS 2019, but rather advice and strategies that will secure the existence of independent spaces in the long run. This will take the form of conversations with other agents of the scene, locally and internationally, who have developed an array of strategies and tools throughout the years. “This time [IAS] is more about helping the spaces, not putting them under pressure to create something for the festival,” say the curators. The goal this year is, rather, to reverse the question, and ask: “What could the festival possibly do for the spaces?”

Another novelty this year is the unprecedented number of international participants, including independent spaces from Europe, Australia, and elsewhere in Asia. According to IAS, these international participants have been selected according to the local, Beijing spaces’ needs — they serve as a reminder that regardless of apparent regional differences in terms of funding and surrounding structures, “many of the difficulties and issues are shared worldwide, as well as the questions raised apparently responding to local circumstances and the possible strategies implemented to tackle them.”

By creating an arena for local and international spaces to coalesce, IAS 2019 hopes to set in motion a continuous exchange network between all of the participating agents, particularly when addressing absences of the systems they belong to, such as a lack of public funding for independent spaces in the case of Beijing.

A performance from a previous edition of the Independent Art Spaces festival

This year’s schedule of workshops are, as expressed candidly by the IAS team, “about sharing all the strategies and tools that these spaces have developed over the years through their practice and get into a discussion, [and to] hopefully create new content” that could be shared with future spaces in the scene, or whoever might be in need of such elements. IAS stresses the urgency for independent art spaces to create unique models based on their own potential, advantages and limitations — particularly in terms of labor. The ideas shared in the workshops are meant to be “self-empowerment tools for spaces about how to reach clarity on ‘what you want to do with the space in the best possible way,’” while also inspiring confidence about the role that each space’s mission contributes to the local art ecosystem.

One theme that will be brought to the discourse is pragmatism, a crucial consideration for independent spaces in the long run: “the need to [re]structure work to create a work [practice] that’s ultimately sustainable,” in the words of Eschbach and Angerer. Elaborating more on what that implies, the curators add: “[it means] running away from self-exploitative practices in a system that borrows elements from larger institutions also built around exploitation.” Other workshops explore curatorial practices adapted to very particular scenarios (such as the absence of a physical space, or “nomadic practice”), and limitations in terms of content creation (such as censorship, a topic that will ring a bell for content creators everywhere).

Now one week into its fourth edition — which runs through the end of the month — IAS constitutes not only a major archival resource mapping Beijing’s independent art scene’s ups and downs over the years, but also a major celebration of the qualities of resilience and tenacity crucial to the city’s art landscape, one that is unique within the context of mainland China, and the wider world.