I’ve traveled quite a bit through Southeast Asia this winter. It is evident views of China are changing — and not always for the better.

At a temple in Luang Phabang, the cultural heart of Laos and a former imperial capital, I eavesdropped as a local guide herded two American tourists through the courtyard and into the large hall.

“There used to be a large, gold Buddha here,” the guide solemnly intoned. “But now it’s gone. The Chinese came, sacked our city, and stole all of our treasures.”

“When was that?” asked one of the clients.

“1888 Invasion. Very bad. Looted everything.”

Even I was a little surprised by the Laotian guide’s accusations of Chinese looting. I’m pretty familiar with 19th-century Chinese history, and I hadn’t heard about any incursions into Laos.

Sunset in Vang Vieng, Laos (photo: Remi Yuan)

Turns out that in 1888 there was an invasion by armies from China, but not by the armies of the ruling Qing Dynasty. The invaders were remnant rebel forces who fled the Qing Empire following the collapse of the Taiping (1850-1864) and Panthay (1856-1873) Rebellions. Retreating commanders took their troops across the border and into Burma and Vietnam where they merged with local indigenous forces to form irregular armies. Nominally under the command of the Vietnamese court, these armies — which became known as the Black Flags — also engaged in extortion and banditry along the Mekong and Red Rivers. The Black Flags fought alongside Vietnamese and Chinese troops to resist French colonial expansion into Indochina in the Sino-French War of 1884-1885. The French victory forced the surviving Black Flags back upriver where they survived by plunder and piracy, including a sack of Luang Phabang in 1887-1888.

It is an unfortunate corollary of historiography that one people’s historical footnote is too often another people’s great tragedy.

I’ve become accustomed to being lectured — and not without good reason — for the sins of my ancestors in China, but in Southeast Asia, it is the Chinese who are the historical villains almost as often as are the European colonialists. It is a narrative which has taken on greater stridency as China looks to assert its hegemony over its smaller neighbors to the south. China’s economic clout, hunger for resources, and military power all cast a long shadow into Southeast Asia.

Related:

Constructing Ethnicity in XishuangbannaArticle Feb 12, 2018

Constructing Ethnicity in XishuangbannaArticle Feb 12, 2018

In Vietnam this week, current and former Vietnamese leaders honored those soldiers who died defending the country during China’s ill-advised invasion of Vietnam in 1979. The 40th anniversary of this war, in which at least 60,000 people lost their lives in less than a month of fighting, has been largely ignored in China.

(In China, the war is usually referred to as a “Self-Protection Campaign” in which the Vietnamese provocations left the PLA little choice but to invade. Basically, the same bullshit excuse the British used to start the Opium Wars.)

These divergent understandings of history can create some uncomfortable cognitive dissonance for Chinese visitors who are increasingly an engine of growth for the tourist economies in Southeast Asia. In 2011, 1.7 million Chinese tourists traveled to Thailand. That number is expected top 10 million in 2019. China is now the largest source for tourists visiting the Indonesian island of Bali, overtaking Australia, while Chinese tourism in Vietnam increased 30% in 2018 over the previous year.

Related:

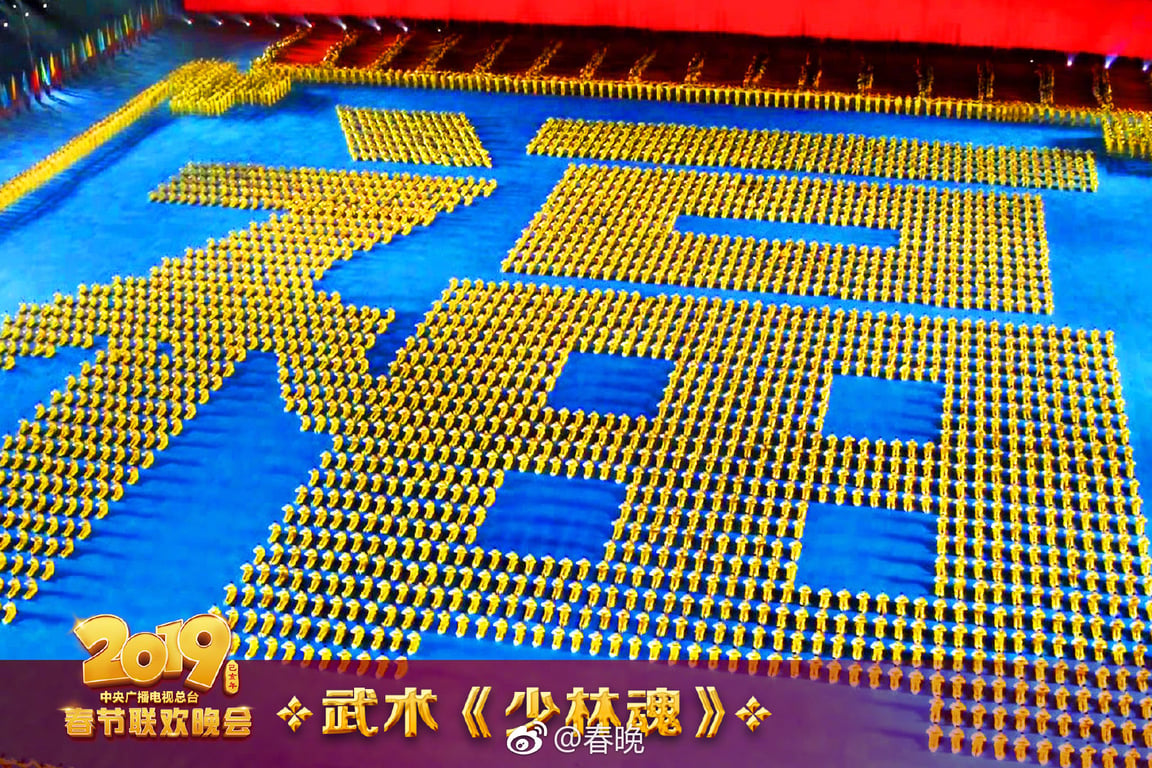

8 Jaw-Dropping Statistics from Spring Festival 2019Key New Year stats, from the number of WeChat hongbao (digital cash-stuffed red envelopes) sent to the number of Spring Festival Gala viewersArticle Feb 11, 2019

8 Jaw-Dropping Statistics from Spring Festival 2019Key New Year stats, from the number of WeChat hongbao (digital cash-stuffed red envelopes) sent to the number of Spring Festival Gala viewersArticle Feb 11, 2019

As an American, I am all too aware of the historical baggage I drag with me wherever I go. The Ugly American isn’t only a stereotype. We exist. In a small airport in the central highlands of Vietnam, I was waiting for a flight to Hanoi when a fellow American started a conversation with me. He was older than I am, probably in his 60s, and he started the conversation by telling me he was flying back to his wife and business in Florida after five weeks with his Vietnamese “girlfriend” (for whom he left a large gratuity as a “thank you” and because “these folks need it.”)

But that wasn’t the weird part of the encounter.

My new acquaintance then launched into a whole speech about how the world’s airlines were controlled by the Jews who ran everything through George Soros and that something called “QAnon” predicted the “assassination” of John McCain and the upcoming assassination of Barack Obama, et. al. for reasons of “child trafficking.” It was some bizarre stuff, especially since this was apparently his go-to conversation gambit when stuck in an airport in the middle of the Vietnamese highlands.

After I cut him off with “I think they’re calling our flight” and “Excuse me, but I have to take this plastic fork and give myself an emergency orchiotomy,” I ended up googling some of the stuff he was saying because none of it made any sense.

Vietnamese rice terraces (photo: Tuệ Nguyễn)

So, if I say there are some Chinese traveling in Southeast Asia with a shocking lack of self-awareness, I do so fully aware many Americans suffer the same affliction. It’s what happens when folks from big countries with strong exceptionalist identities hit the open road.

That said, I learned about the Vietnam War in high school. There are television programs, films, books, and documentaries describing in excruciating detail the extent to which American involvement in Southeast Asia unleashed an unholy hell on the people living there. Even today, over 80 million unexploded bombs remain in the Laotian countryside where they kill and maim hundreds of people each year. Nearly five million people were exposed to Agent Orange and other chemical defoliants the United States used during the Vietnam War. Despite an announced program to clean up the contamination, there are still nearly three million people dealing with the long-term effects of exposure including suffering from congenital disabilities, neurological conditions, and other horrific illnesses.

It’s not a comfortable feeling traveling to a place where people like me did so much damage, and I get why not everyone is happy to see me there no matter how much money I’m contributing to the local economy.

Will Chinese travelers learn to cope with their own baggage both historical and that which comes with being seen as representatives of a global power and regional hegemon?

According to Brian Eyler, Director of the Southeast Asia program at the Stimson Center and author of the forthcoming book The Last Days of the Mighty Mekong, China’s reputation among the countries in Southeast Asia has taken a bit of a hit over the last decade.

“Already Vietnam’s relations with China were strained by historical enmities leading back millennia but compounded by China’s actions in the South China Sea,” says Eyler.

“In Laos, Belt and Road projects like the high-speed railway and numerous dams and agricultural plantations were talked about as ‘Made by China, Made for China’ as a play on words with the ‘Made in China’ slogan. This rise in anti-China sentiment forced a change in government in January 2017 in Vientiane.”

China has attempted a charm offensive in the region, launching the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism in 2016, but many people in Southeast Asia still are wary about China’s growing influence and are sometimes ambivalent to the growing numbers of Chinese tourists.

Back in Luang Phabang, a tourist flees a local restaurant’s restroom, imploring her travel companion in Beijing-accented Mandarin to see — and smell — for himself.

“It’s so dirty! How can you take me somewhere where the bathroom is so dirty?”

The Ugly American in me sadly watches as a metaphorical torch is passed gently along.

Cover photo: Chinh Le Duc on Unsplash