In 1922, Albert Einstein traveled around Asia accompanied by his then-wife, Elsa. Einstein’s diaries of that trip, recently published for the first time in English, suggest that the renowned physicist, whose expansive views of the cosmos — and his discovery of the photoelectric effect — would earn him the Nobel Prize, had some shockingly narrow attitudes when it came to people from other cultures.

Albert and Elsa arrived in Shanghai in November 1922 and it was there that Einstein received the official notice of his Nobel Prize (although he had heard radio reports announcing the award during his travels). In Shanghai, they dined with the painter and calligrapher Wang Yiting and took in a performance of Kunqu Opera.

A planned trip to Beijing to lecture at Peking University was canceled after the official invitation from Chancellor Cai Yuanpei failed to reach Einstein in time and the physicist and his wife sailed on for Japan. Einstein returned to Shanghai once more, in January 1923, and gave a New Year’s Day lecture on general relativity before departing onward to Jerusalem.

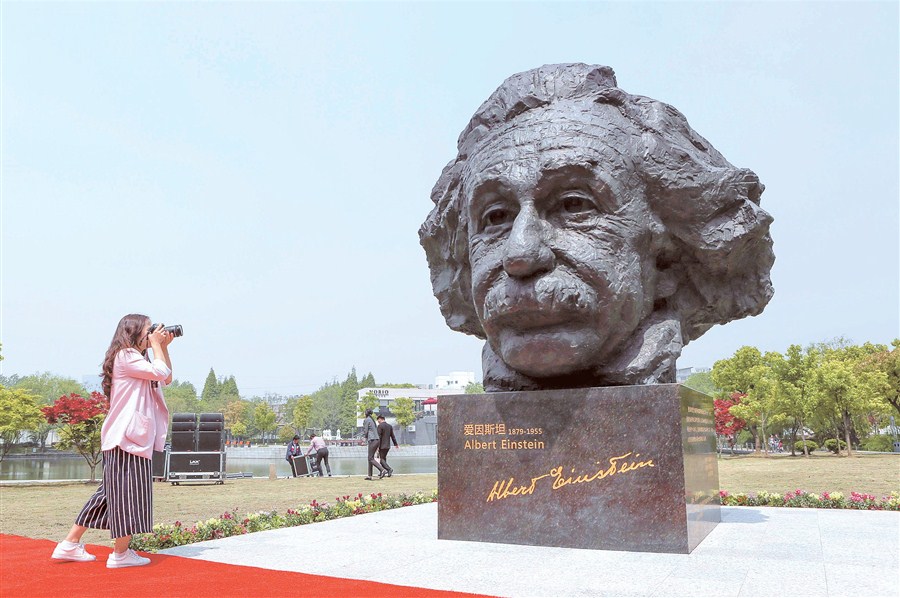

A statue in Shanghai’s Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park (photo: shine.cn)

While Einstein’s arrival in China generated a great deal of excitement among both the foreign and Chinese intellectual community, Albert’s impressions of the country were decidedly mixed. In Shanghai, he observed, “In the air, there is a stench of never-ending manifold variety.”

His impressions of China’s people were equally disparaging, describing them as an “industrious, filthy, obtuse people.”

“Chinese don’t sit on benches while eating but squat like Europeans do when they relieve themselves out in the leafy woods. All this occurs quietly and demurely. Even the children are spiritless and look obtuse… It would be a pity if these Chinese supplant all other races. For the likes of us, the mere thought is unspeakably dreary.”

Whether it’s fair to cherry-pick the most obviously racist bits from a person’s diary — Einstein would later be involved with numerous civil rights causes and organizations in the United States and around the world — Einstein’s comments are sadly reflective of attitudes toward other races held by Europeans and Americans in the early 20th century.

Yet these same attitudes were all too prevalent in China as well, suggesting an internalization of pseudo-scientific racist and racialist attitudes coded in the language of civilization and modernity. As Frank Dikötter and others have argued, the fascination with race in China around the turn of the 20th century was intimately linked, by reformers and revolutionaries alike, with defining and strengthening the Chinese nation at a time when aggressive imperialist powers were carving up civilizations into colonies and concessions.

The idea of “race” isn’t specifically a Western notion — Chinese revolutionaries including Zhang Binglin, Zou Rong, and even Sun Yat-sen, drew on a body of underground anti-Manchu writings which had been surreptitiously circulated for centuries — but the idea of race as part of scientific system of knowledge was strongly influenced by new constructions of race in the West, especially a belief that racial difference was a matter of biological determination rather than cultural context.

Related:

Wǒ Men Podcast: Black Panther and Attitudes to Race in ChinaArticle Mar 30, 2018

Wǒ Men Podcast: Black Panther and Attitudes to Race in ChinaArticle Mar 30, 2018

Yan Fu (1854-1921) translated Thomas Huxley’s Evolution and Ethics in 1895. Yan’s translations of Huxley, and of Herbert Spencer, had a profound influence on Chinese attitudes of race and eugenics. Liang Qichao (1873-1929) was one of China’s greatest writers and reformers and was well-known for his keen insights into politics and society, but Liang’s views on race were badly influenced by contemporary attitudes of scientific racialism when he wrote about how brown-skinned and black-skinned races were inherently less civilized and intelligent.

In his own famous travel diary, recorded during a visit to the United States in 1903, Liang criticized the practice of lynching, but not because of the racism. Liang wondered how the government could allow extralegal rabble to administer justice. As for the victims of the lynch mobs, Liang wrote: “To be sure there is something despicable about the behavior of blacks. They would die nine times over without regret if they could possess a white woman’s flesh.”

Einstein in 1921 (photo: F Schmutzer, public domain)

Liang’s mentor, Kang Youwei (1858-1927), famously advocated eugenics, including introducing ideas about education for woman and pre-natal care, but Kang also suggested that interbreeding could “whiten” the Chinese race, and so improve the strength and character of the people.

In 1923, around the time of Einstein’s visit to China, one of the first ‘scientific’ works on Zoology included a section on “Africans.”

This is not to say that Albert’s comments aren’t racist. Nor is it saying that Chinese at the time were any more racist than other intellectuals of the same era. In fact, the insidious part of China’s attitudes toward race then (and to some extent even now) is how pseudo-scientific racialist theories came to be internalized by people who were themselves the victims of racism.

And it’s also worth noting that not all of Einstein’s comments about China were dismissive.

In his book China and Albert Einstein: The Reception of the Physicist and His Theory in China, 1917–1979, historian Hu Danian describes a banquet in Einstein’s honor and hosted in Shanghai by such luminaries as Zhang Junmai (Carson Chang) and Yu Youren, then president of Shanghai University. After a succession of toasts, Einstein kindly thanked his hosts, remarking, “As for Chinese youth, I believe they are bound to make great contributions to science in the future.”

—

Cover image from Katya Knyazeva’s scrapbook

You might also like:

Karl Marx, Cai Yuanpei, and the Legacies of May FourthArticle May 04, 2018

Karl Marx, Cai Yuanpei, and the Legacies of May FourthArticle May 04, 2018

Young Chinese React to “Qipaogate”, Mostly with ConfusionArticle May 03, 2018

Young Chinese React to “Qipaogate”, Mostly with ConfusionArticle May 03, 2018