#Rogue Historian

What do Hillary Clinton, Chinese Admiral Zheng He, Amy Winehouse, and Chiang Kai-shek have in common? They are all pigs Read More

While the centennial of the 1919 May Fourth Movement is still a year away, 2018 has no shortage of anniversaries related to this epochal moment in China’s modern history and to the intellectual and political movements to which it gave birth.

Karl Marx is getting celebrity treatment ahead of his 200th birthday this Saturday with a series of academic conferences including a speech by Marxist-in-Chief Xi Jinping lauding the German philosopher’s contributions to China’s socialist revolution. State media has even introduced a new chat show “Marx was Right,” to introduce Marxist theory to young people raised in an era of conspicuous consumption.

The former library of Peking University in downtown Beijing. Today it is a museum to the May Fourth era.

At the May Fourth Memorial Hall in downtown Beijing, a temporary exhibit mixes details from Karl Marx’s life and work with memorabilia from China’s revolutionary past including a document expelling a youthful hooligan named Deng Xiaoping from France.

Across the parking lot, inside a red brick building built in 1918 to house the Peking University library, is a reproduction of the office of Cai Yuanpei (1868-1940), university chancellor and a towering intellectual figure in the New Culture Era which culminated in the demonstrations on May 4, 1919. This past January marked the 150th anniversary of Cai Yuanpei’s birth.

Memorial to Cai Yuanpei at his former home in Beijing located at #75 Waijiaobu Hutong in Beijing.

Cai Yuanpei bridged the gap between the age of classical scholarship and a new era obsessed with modern – often interpreted as Western – models of education. At just 26, he was appointed to the prestigious Hanlin Academy – a think tank/holding pen for the empire’s best and brightest. But Cai was also influenced by the political and intellectual currents of his time. In 1904, while traveling in Europe, he joined the Tongmenghui, a coalition of revolutionary groups organized by Sun Yat-sen and Huang Xing.

Cai Yuanpei (1868-1912) during his sojourns abroad in Europe. Later Cai would become the President of Peking University.

While in Europe, he attended the University of Leipzig in 1907 before returning to Beijing following the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912 and serving briefly as Minister of Education in the new government. After another brief academic sojourn in Europe, Cai Yuanpei returned to China in 1916 to become the President of Peking University.

If we are to compare the New Culture Era to The Avengers, Cai Yuanpei is Nick Fury. During his tenure at Peking University, he brought together a wild and disparate group of intellectuals and scholars.

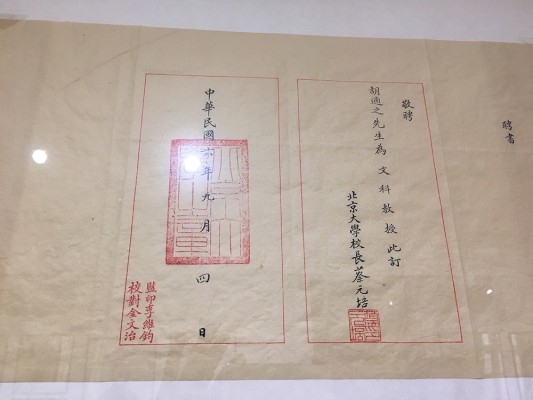

Letter appointing Hu Shih as a professor at Peking University. Displayed at the May Fourth Memorial Hall in downtown Beijing.

Cai appointed Hu Shih, then a 24-year-old doctoral candidate at Columbia University under John Dewey, to be his Professor of History and Philosophy. For his Dean of Faculty, Cai hired the iconoclastic firebrand Chen Duxiu, publisher of the influential journal of ideas New Youth. The writer Lu Xun, the painter Xu Beihong, and the anarchist-philosopher Liang Shuming all roamed the hallways and classrooms of Peking University during Cai Yuanpei’s tenure.

It was a heady time. China in the years after the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916 teetered on the brink of becoming a failed state. A government existed in Beijing but it was a revolving door of presidents, premiers, warlords, and militarists which did little to inspire confidence. Meanwhile, many parts of the country were under the de facto control of foreign powers with Japan taking an increasingly aggressive position toward expanding its influence in China. These were not good times and for many students – and their teachers – these seemed like end times. The result was an explosion of ideas. Nothing was off the table. Liberalism. Socialism. Anarchism. Utopianism. Mr. Science. Mr. Democracy. If it was new, modern, scientific, and, preferably, foreign then it was an idea worth sharing.

[pull_quote id=1]

The era culminated in demonstrations in Beijing and other cities around the country on May 4, 1919. Students took to the streets to protest China’s treatment at the Paris Peace Conferences that year and deals which had handed German concessions in Shandong over to Japan. 3,000 students from over 13 universities and schools marched to Tiananmen and through the streets of the capital. The movement spread to other cities and led to a general strike which lasted over a month. Authorities arrested many of the student leaders and several students were beaten and injured in scuffles with police. Cai Yuanpei (briefly) resigned his post out of protest over the treatment of the students in police custody.

In 1919. over 3,000 students from around Beijing protested China’s treatment at the Paris Peace Conference in what became known as the May 4th Demonstrations.

What does this have to do with Karl Marx?

After the May 4th demonstrations, many students from this generation realized that all the ideas in the world would be of little use if they didn’t have a country to practice those ideas. If China was weak, the Chinese would be pushed around and bullied by the rest of the world. Many of those who had experimented with more idealistic solutions to the country’s problems now became fixated on strengthening the nation. The horrors of World War I and the reality of imperialism also led to a growing disillusionment with the West as a source of solutions for China’s problems.

Some took a direct approach to the problem of weakness. In 1924, the Nationalist Party of Sun Yat-sen established the Whampoa Military Academy with aid from the Soviet Union. The first commandant of the academy was a younger protégé of Sun’s named Chiang Kai-shek. The goal was to build the core of an army which would could unify the country – by force if necessary – and defend the nation.

[pull_quote id=2]

Others took a different view of national strength. China was weak because the revolution which overturned millennia of imperial rule had failed to truly change the fundamental weaknesses and inequality of society. A new blueprint for the nation was needed.

One of Cai Yuanpei’s hires had been for the library. There he installed Li Dazhao, who would become an early advocate for Bolshevism as a solution to China’s problems.

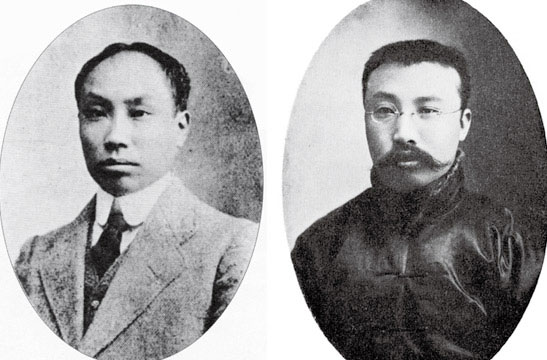

Chen Duxiu, Dean of Faculty at Peking University, and Li Dazhao, head librarian, would go on to become two of the most influential figures in the formation of the Chinese Communist Party.

Writing exactly a century ago this year, Li proclaimed:

The crashing waves of revolution cannot be halted by today’s capitalist governments because the mass movements of the twentieth century have brought together world humankind into one great mass…In the face of this mass movement historical remnants – such as emperors, nobleman, warlords, bureaucrats, militarism, capitalism – and all other things which obstruct the advance of this new movement will be crushed by the thunderous force…On all sides one sees the victorious banners of Bolshevism and everywhere one hears the victorious songs of Bolshevism. Everyone says that the bells are ringing! The dawn of freedom is breaking! Just take a look at the world of the future, it is sure to be the world of red flags!

One wonders what influence Li Dazhao’s enthusiasm may have had on his intern, a young man from Hunan without the intellectual wattage necessary to be a student at Peking University but who was a hanger-on in university circles including working as a library assistant. That young man’s name was Mao Zedong.

Ultimately, Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu, who, having been forced out from Peking University following the May Fourth demonstrations, turned his New Youth magazine into a Marxist study journal, inspired Mao and other young men to form China’s Communist Party in 1921. For many intellectuals, especially those on the political left, Marxism offered a modern and scientific schematic for China’s problems. The Soviet Union represented a possible path forward.

The rest, as they say, is history etched in teleology.

The trouble with Marx in China is that there were of course more than just two outcomes from the May Fourth Era. Ultimately, the struggle between the Communists, who would much later be led by Mao Zedong, and the Nationalist Party led by Chiang Kai-shek would absorb much of the oxygen in the debate over China’s future. But it would be a mistake to see the May Fourth era as a single unbroken road leading inexorably to China’s redemption under Mao and rejuvenation under Xi.

Marx may be getting most of the attention this year, but we should not forget the possible pasts represented by Cai Yuanpei, the intellectual omnivore, the university president unafraid of wild thinkers.

#Rogue Historian

What do Hillary Clinton, Chinese Admiral Zheng He, Amy Winehouse, and Chiang Kai-shek have in common? They are all pigs Read More

#Rogue Historian

The Chinese State is cracking down on global religions, but why? Read More