I first met Simon Song over drinks somewhere in downtown Shanghai. When he told me he was a photographer, I knew he meant of the fine art variety — Simon stands around six feet tall, with long, thick hair wrapped into a bun, and comes dressed in a wardrobe of flowing vintage numbers. His quiet glow would mark him either an artist or a well-practiced meditation enthusiast.

It wasn’t until later when I became curious and looked into his art, that I came to understand the unique kind of photography Simon is engaged in. His work is a kind of meticulously sculpted analog, intended for viewing, soaking in, and mulling over. It was interesting, a pious follower of the analog format, in a world where everyone has gone digital. His dizzying impressions of cityscapes warrant some long, luxuriant stares.

A couple of weeks later, Simon and I met up in a coffeeshop for a candid chat about his work, his process, his thoughts on analog photography, and his views on art in general.

“Through Observation” – Simon Song

First off, could you tell us a little about yourself? How did you find photography?

Growing up as a kid, I did a little bit of everything. Only after I got to college did I find my real interest was in more creative work, like painting and sketching. Later on, I realized the camera could be a great tool for me. I ended up going on to the UK, to learn photography at the London College of Communication. Everything else just kind of fell into place.

At first, in China, I was in a program called Electric Information Engineering. Nothing to do with photography, but I found I just wasn’t interested in it. I kind of explored a bit — reading books, looking through history, and trying out different things. I learned painting and sketching, and at that time, lomography was quite popular, so I was playing around with a lot of vintage cameras. I was amazed by their almost magical feeling. That was my first time working with analog, and from there I just got more and more interested in it.

The program I ended up in at LCC is famous for having strong analog facilities, so I spent a lot of time in the darkroom, manipulating the colors, blacks and whites… that’s really how I developed the language of my work, manipulating in analog and kind of crafting the image myself.

“Details 7”, Simon Song

What is it that draws you so strongly to analog? What are the advantages there?

I wouldn’t really say there’s an advantage or anything like that. I would say my work kind of relies on this feeling of handmaking the image. Every movement you do, layering, or burning something, or changing the colors… you have to set it manually and do it by hand. I enjoy the action of every effect I perform on an image, rather than in Photoshop, where you can just draw it out and adjust the settings in an instant. I can’t work that way, but these are all just my own thoughts.

Nowadays there are a lot of fine art photographers who use analog, like large format. They’re really taking advantage of that large negative to produce really fine details on large print. But for me, the main point of analog is more about the artist’s crafting of the image.

That makes sense, given your entry point into creative work was painting and sketching. Analog is almost like a middle ground between today’s digital photography and something like painting, and sometimes maybe those limitations can pull more out of you as the artist.

Sometimes it could be limitations, and sometimes it could be new opportunities. And it’s interesting you mention painting. In the darkroom, I almost feel like I’m painting with light, instead of just developing an image. When I apply so much work and labor into making that image, you can feel it in the end result.

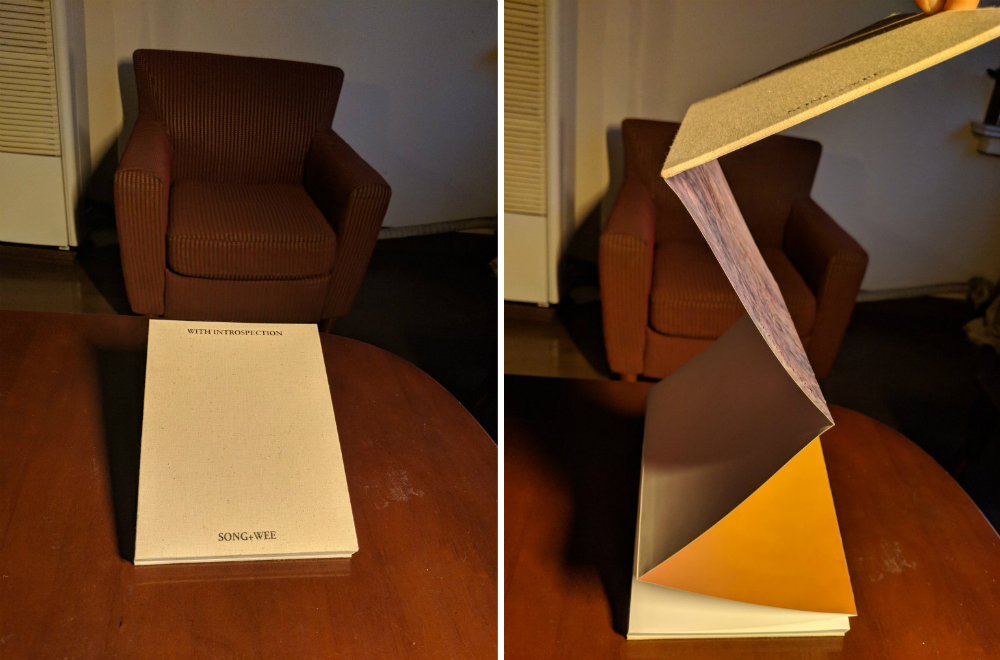

With Introspection is a self-described coffee table book, a collaboration between Song and digital photographer Timothy Stuart Wee

With your photos from the collaborative project With Introspection, you can tell immediately that there’s something different about them, that it’s not just someone with a DSLR. I noticed the title of each of those pieces is a set of latitude/longitude coordinates. Could you tell me some about that series?

Sure, that’s all a series of locations, we made it for our book. The idea is, like when you’re reading a novel, and they describe things, but they don’t give you the whole picture. They kind of give you a lead, bit by bit, “this corner is like this,” or “the coffee shop was this kind of color.” Put it together and it kind of forms the sensation of that place.

For us, we felt like just presenting the view of a location only scratches the surface. Those coordinate points, some of them are places we’ve never been to. But maybe we’ve heard about it in the news, or in movies, or in literature.

[pull_quote id=”2″]

So it’s almost like travel photography without traveling. You’re trying to take the feeling of the place based on what it means to you, and represent it through images you have, or ones you can manipulate.

Well, a lot of the photos really are from those places.

But the viewer doesn’t know which is which?

I would say it doesn’t matter. I got this idea from traditional Chinese shanshui [山水 literally, “mountain and water”] ink paintings of landscapes. There’s a kind of description of that genre that says, these paintings are from the view of an observer. It’s the view of the person who painted it, all that imagery filtered through the artist, and in that sense he’s kind of projecting himself onto the painting. The same applies when we’re making an image. As the people observing this place or location, we kind of project ourselves and our own feelings onto the image, to recreate that sensation.

“69.2176, -51.1125”, Simon Song

Actually, shanshui painting is one of my main inspirations. But I’m always trying to avoid the look of shanshui painting itself. I’m trying to use a different medium, and also the subject is totally different — it’s not the natural landscapes of shanshui painting. I was trying to recreate this energy of shanshui, so I had to distance myself from the look of it, which could potentially invoke nostalgia.

And you don’t want that.

Correct.

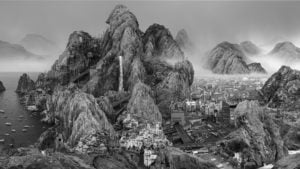

There’s another artist, Yang Yongliang, who also uses shanshui-style imagery, building his images from photos of modern cityscapes.

Sure, but I would say that his approach is totally different.

Yang Yongliang, “Endless Streams”, 2017, © Yang Yongliang / Courtesy Galerie Paris-Beijing

Absolutely. He’s imitating the aesthetic, or the image of shanshui painting, and you’re trying to capture some of the energy, or maybe the base nature of it, without taking on the look. That’s an interesting challenge too, to try and have something that’s inspired by that classical form, but then make the conscious decision that you don’t want to rely on the nostalgia of it, or make it some kind of exotic thing. Could you walk me through what your process is like, with your shanshui-inspired, geographic coordinate pieces?

With that series, the approach varies piece to piece. Some of them are places we’ve been — we pay a visit for the project, and we take a lot of snaps, sometimes more landscape photos, and all we know is that they’re going to be used to make the image. Later on, after the shoot, I make some selections, and lock myself in the darkroom with all the negatives, trying out a lot of different combinations.

But with the one for Yunnan, for instance, we never went there. I made selections from a bunch of nature photographs, even garden photos I took, and then tried some different mixtures between them to find the right feeling. In that case, I kind of just proceed on feeling.

[pull_quote id=”3″]

Later there’s a London one. With that one, I basically already know the image I want, so it’s just a matter of finding that image, to help me compose the piece. I knew the image I wanted would have this kind of misty, cold feeling, like the back alleys there. That’s my own feeling, based on my experience in southeast London, and the four or five years I spent there. I know the image, so I need to find it, or even just shoot something to compose that kind of result.

Why do you think it is that your work is so intimately tied to a sense of place?

Well that’s also my own interest. I’ve always been interested in the relationship between people and space, space and memory. That’s why I went the sociology route, and took courses focused on urban culture. Photography and Urban Culture was the name of my program. In that course I learned quite a lot about sociological theories, and the debates within the field. I would say that gave me a lot more knowledge, and informed my understanding of the relationships between place, space, people, and history.

I’m trying to bring this all into the world, either with my selection of the image, or through my manipulation of its final look. I’m figuring out how to reflect my own understanding of the space, and what the space means to people living there.

“51.4900,-0.0924”, Simon Song

Do you think artists have a responsibility to be informed or knowledgeable in the stories they’re telling through their work?

Hmm. That’s a tricky question. I would say artists are responsible for making their work comprehensive, or making their representation as precise as they can. But I don’t believe that the art world should be telling a story, or say, framing anything as a rule. It’s still mainly for the audience to interpret. It’s a kind of relationship between us and the audience. The artist can’t dominate that conversation. The artist only gathers all the information, and knowledge, and forms it into a kind of reflection or representation for the audience to interpret. Rather than say, “that’s my work, welcome and here it is.” I mean, I don’t believe artists have this right, to dominate the conversation like that.

It goes back to what you were saying about creating this kind of work, and wanting it to be like a book. You don’t want it to be like a movie, where you tell the viewer everything. In a book there’s more room for interpretation, where you’re the one presenting the image, but the readers themselves have a lot of room to think. It’s not just, “here’s my work, here’s what it means, and the message, here’s what you need to know.”

Exactly. Like this book With Introspection, we made it into this accordion-style coffee table book because we wanted to affect how the reader would interact with it. I always want my work to have a playful quality — I was really struck by the French idea of tableau vivant, a living image. One that people can be drawn into, and kind of explore for themselves.

“Places 1”, Simon Song

What are you looking to do in the future, or what’s next for Simon Song?

Right now my main focus is still on exhibitions, and getting deeper into that scene. But I would say, if I got the opportunity, I would love to do some work for public spaces. Like the metro, or squares where people walk and gather, or even a coffee shop. I’d really love that.

That could be a fitting place for your work. If you do a piece that captures a place and it’s essence, I’m sure people would appreciate having it in the metro for that place, or in a shop somewhere.

Last question: What’s something that people might not understand about art, or analog photography, or your work in particular, that you would choose to explain to our readers?

Hmm. I would say, with analog photography, or fine art photography, or my own work, you just have to be open to it. You have to kind of give up your preconceived notions. The image doesn’t have to be about anything, or documenting something. An image itself is still an object, let’s treat it like an object. It doesn’t necessarily have to have a purpose — it could be abstract, emotional, or purely about sensation. Just explore that. Dig into the image, and find the way to experience it.

More artist interviews on RADII:

Art of Pianzi: Psychedelic Cats, Buddhist Classics, and a Human Face AbacusArticle Mar 11, 2018

Art of Pianzi: Psychedelic Cats, Buddhist Classics, and a Human Face AbacusArticle Mar 11, 2018

Mindful Indulgence: Lu Yang’s Art as Spiritual EntertainmentArticle Nov 04, 2017

Mindful Indulgence: Lu Yang’s Art as Spiritual EntertainmentArticle Nov 04, 2017