A US administration looking to score points with nativist know-nothings on the back of vulnerable immigrants. A newly assertive China led by a government frightened of change but eager to appease a vocal middle class. Chinese commercial interests colluding with government officials to exploit a rising sense of nationalism as part of a basket of tactics to stymie foreign competition. Chinese and American diplomats banging tables as they try and resolve a trade dispute which threatens to escalate into a broader conflict.

Welcome to the world… in 1905.

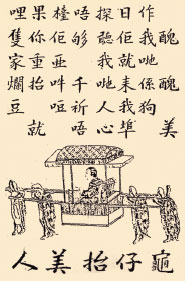

On May 10, 1905, the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce passed a resolution urging their fellow Chinese nationals not to buy American goods. Within a week, word of the boycott spread via recently installed telegraph lines and along newly built railways throughout the country. From Guangzhou to Xiamen to Shanghai, Chinese citizens stopped buying American.

This was a new form of resistance different from the barbaric yawp of the Boxers, a form of resistance which was immune to the crude pressures of boots and gunboats. As Robert Bickers, once wrote: “Boxers could be slaughtered by foreign troops, but nobody could be forced to smoke an American cigarette.”

But the motives behind the boycott were as diverse as the actors who made it happen.

There was a new generation of students, many of them worldly from having studied abroad while others had been radicalized at home through immersion in a rapidly growing culture of newspapers and magazines. These students were ready to move away from blind anti-foreignism toward a more sophisticated anti-imperialism. Theirs was an aggrieved form of nationalism, sensitive to injustices against Chinese citizens in China but also, increasingly, to the plight of the Chinese diaspora spread throughout the world.

[pull_quote id=1]

Chinese merchants, especially those in the commercially dependent and industrially advanced areas around Shanghai, faced stiff competition from American imports. For example, China was an important export market for US flour manufacturers. The transfer of flour milling technology allowed local companies, starting with the Fu Feng Flour Milling Company in 1900, to begin producing high-quality flour domestically. By 1904, Fu Feng was joined by six other companies near Shanghai along with another two mills based in China’s northeast. Nevertheless, a surplus of wheat and artificially low transport costs meant that US flour exports to Asia continued to grow by 30% over the same period. Other industries also suffered from intense foreign competition and a treaty-bound Qing government could do little to protect domestic commercial interests.

But it was the treatment of Chinese immigrants in America and attempts by the US government to restrict Chinese migration to the United States and its territories which brought these disparate interests together in collective action.

Former Secretary of State John W. Foster (grandfather of John Foster and Allen Dulles) writing in The Atlantic Monthly in January 1906 blamed the boycott on a clash between Chinese nationalism and American nativism:

The Chinese boycott of American goods is a striking evidence of an awakening spirit of resentment in the great Empire against the injustice and aggression of foreign countries. It seems singular that its first manifestation of resentment should be directed against the nation whose government has been most conspicuous in defending its integrity and independence. The explanation of this is that the boycott movement owes its initiative, not to the Chinese government, but to individual and popular influence, and is almost entirely the outgrowth of the ill-feeling of the people who have been the victims of the harsh exclusion laws and the sufferers by the race hatred existing in certain localities and classes in the United States.

Tension over Chinese immigration to the United States intensified in the 1870s as the end of the railroad boom threw Chinese and white laborers into competition for jobs. Anti-Chinese violence spread throughout the American West. Lynch mobs murdered hundreds of Chinese immigrants in California, Wyoming, Oregon in a series of bloody incidents in the 1870s and 1880s.

In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act which severely curtailed Chinese immigration to the United States despite earlier treaties with the Qing government which had stipulated free migration. Subsequent laws further targeted the Chinese community. The Scott Act of 1888 made it difficult for Chinese nationals who had gone back to China temporarily to return to the United States. Other laws deprived Chinese of civil liberties and legal rights granted to immigrants from European countries.

An 1894 treaty established an absolute 10-year moratorium on all Chinese laborers coming to the United States with a provision that the terms would be automatically extended for another ten years if neither side expressly declared their desire to withdraw from the treaty at least six months prior to the agreement’s initial expiration in December 1904.

At the same time, returnees to China brought home stories of American racism and humiliation inflicted on Chinese in the United States. In 1903, the Chinese Military Attache in San Francisco was harassed and assaulted by police. Unable to bear the humiliation, he committed suicide the next day. Later that same year, police in Boston stormed the city’s Chinatown in an immigration raid that led to 234 incarcerations but which found few actual illegal immigrants. Even a member of the imperial family, Pu Lun and his delegation, were harassed by immigration officials and local police when they attended the St. Louis Exposition of 1904.

The boycott put Qing officials in an awkward position. On one hand, this wave of nationalist resistance was putting useful pressure on the Americans, but the court, only a few years removed from the Boxer debacle of 1900, was also leery of popular sentiment. US officials in China tried to force the government to end the boycott. Some local officials, notably Yuan Shikai in Tianjin, acted forcefully to prevent economic and other unrest from spreading to their city. In Shanghai and Guangzhou, officials expressed their sympathy to US officials about the situation, but also made it clear that this was a matter beyond their control. The head of the newly established Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Yikuang (1838-1917), also known by his title Prince Qing, counseled the court to wait and see.

By September, the unity of the movement had weakened. With some ports still open to trading in American products, those merchants in cities which tried to abide by the boycott started to feel the pinch. The Qing court also announced that the US government had promised to treat Chinese visitors to the US favorably and that continuing the boycott threatened international amity.

Ultimately, the boycott could not be sustained. The exclusionary laws and treaties would continue for another 30 years, and anti-Chinese racism and US immigration policy restricting Asians coming to the US would remain in place for decades after that. Nevertheless, the 1905 Anti-American Boycott demonstrated the power of collective action and the effectiveness of using economic pressure to get the attention of US politicians and the electorate.

With the current US President threatening to drag the United States into a costly trade war with China, it’s worth remembering the historical linkages between national pride and economic interests, and the legacy of the Summer of ’05.

—

Sources and further reading:

Robert Bickers, The Scramble for China: Foreign Devils in the Qing Empire, 1832-1914. (Penguin, 2012)

Daniel J. Meissner, “China’s 1905 Anti-American Boycott: A Nationalist Myth?” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations, Vol. 10, No. 3/4 (Fall-Winter 2001), pp. 175-196

John Pomfret, The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom: America and China, 1776 to the Present. (Henry Holt & Company, 2016)

Shih-shan H. Ts’ai, “Reaction to Exclusion: The Boycott of 1905 and Chinese National Awakening.” The Historian, Vol. 39, No. 1 (November 1976), pp. 95-110

Sin-Kiong Wong, “The Making of a Chinese Boycott: The Origins of the 1905 Anti-American Movement.” American Journal of Chinese Studies, Vol. 6, No. 2 (October 1999), pp. 123-148

You might also like:

The Execution of Yue Fei: 875 Years of Patriotic MythArticle Jan 27, 2018

The Execution of Yue Fei: 875 Years of Patriotic MythArticle Jan 27, 2018

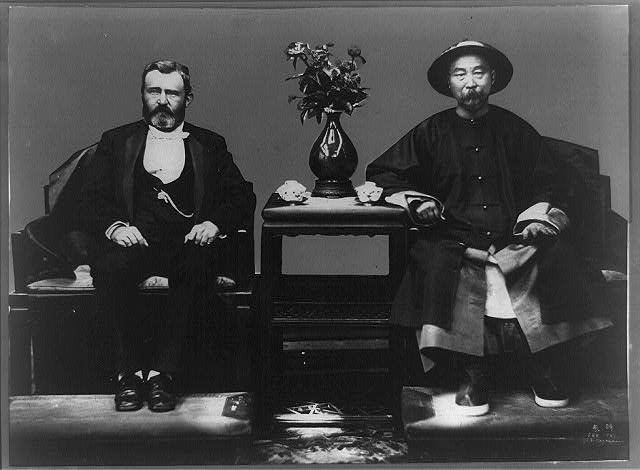

When Ulysses S. Grant Met General Li (Part 1)Article Jan 21, 2018

When Ulysses S. Grant Met General Li (Part 1)Article Jan 21, 2018