I just finished Ron Chernow’s doorstopper biography of Ulysses S. Grant, the much-anticipated followup to Chernow’s Hamilton bio, which became the improbable source material for a hit musical. Clocking in at over 1,000 pages, Chernow’s latest is good winter holiday beach reading, if for no other reason than the hardcover edition weighs enough to stun a flesh-crazed tiger shark.

Grant’s was a life lived in many acts: Soldier. Drunk. Failed businessman. Drunk. General. Drunk. President. Failed businessman again. Tomb.

Grant was also the first US president to visit China.

Although no longer in office, Grant toured China in 1879, one of the last legs of a round-the-world tour taken in part to escape the bruising politics and scandal that characterized his second term as US president. Suggestions that Grant would try for a third term in the 1880 presidential election dogged him throughout his voyage, and Republican supporters back home actively encouraged Grant to remain abroad to let the negative press fade and be replaced by a new persona: global statesman.

Grant was careful to describe his visit to China as that of a mere tourist, but the Qing government couldn’t resist the opportunity to enlist the former US president to help mediate a growing dispute with Japan over — surprise, surprise — the status of the islands known as the Ryukyu in Japan and the Liuqiu in Chinese. The Meiji Government of Japan had begun to test the willingness of the Qing court to defend their control over Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands, and the Qing government wanted Grant to help avoid a costly war with Japan.

Grant was careful to describe his visit to China as that of a mere tourist, but the Qing government couldn’t resist the opportunity to enlist the former US president to help mediate a growing dispute with Japan

Grant, his wife, and his secretary John Russell Young arrived in Guangzhou from Hong Kong in May 1879 on the iron-hulled USS Ashuelot. He was greeted there by nearly 100,000 spectators, who lined the street from the waterfront to the office of the Governor-general Liu Kunyi, where the Grant party got their first taste of Chinese hospitality: an 80-course luncheon featuring dim sum favorites like pork siu mai, as well as bird’s nest soup, roast pigeon, and boiled duck’s feet with time between servings for a hit on a tobacco water pipe and servants behind each chair keeping diners cool with enormous fans.

Grant had by this time mostly overcome his lifelong battle with alcohol, and for the duration of the China trip kept his toasts perfunctory, not succumbing, as future visitors to China would, to the mind-numbing effects of the baijiu. His hosts were less abstemious. A newspaper account of the feast noted that the “Chinese were more used to foreign liquors than the foreigners to Chinese food.”

Sailing north on the Ashuelot, Grant next visited Shanghai, where he once again received an enormous welcome, this time from the international community. The Bund was lined with flags of all of the nations of the Shanghai concessions, and Grant’s ship was greeted with a double salute from forts and ships along the river. The gates leading to the settlement were ornamented with flowers, and the local band even stumped up a rendition of “Hail, Columbia.”

A newspaper account of Grant’s welcome feast noted that the “Chinese were more used to foreign liquors than the foreigners to Chinese food”

Local officials paid their respects as well, and fire brigades and militia members from the Chinese city took part in a torchlight parade in Grant’s honor. The front of the US Consulate was decorated with Chinese-style red lanterns, each with a single letter spelling out: “Washington, Lincoln, Grant. Three Immortal Americans.”

A report published later in The New York Times called it “The grandest display ever made in the streets of Shanghai,” and news of the lavish receptions given to the former president traveled around the world, adding to the luster of his reputation back home.

From Shanghai, Grant’s entourage steamed north to Tianjin on their way to Beijing. As in Shanghai, the city of Tianjin turned out to welcome their American celebrity guest.

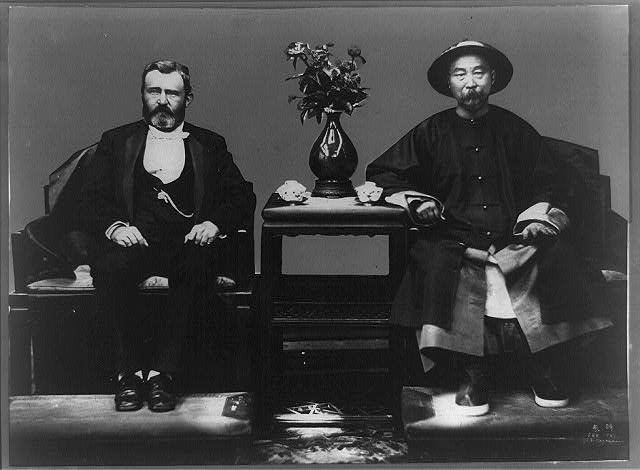

In Tianjin, Grant had the familiar experience of sitting down with a general named Li: Li Hongzhang, at the time the most famous and influential official outside of the capital, made a particular point of meeting Grant. An earlier biography of Grant records a characteristically immodest Li proclaiming, “You and I, General Grant, are the greatest men in the world, having subdued the two greatest rebellions known in history.”

In Tianjin, Grant had the familiar experience of sitting down with a general named Li

The following day at a banquet in Grant’s honor, Li Hongzhang mixed with the international diplomats and their wives. John Russell Young, whose job it was in part to chronicle Grant’s voyage, recalled that Governor-general Li was chatty and sociable, even sharing a glass of French wine with the diplomat’s wives, The North China Herald noting that this was “the first instance on record in which the Viceroy [Li] has met and been introduced to foreign ladies in public.”

Following the dinner, Grant and Li went outside to the terrace to enjoy a quiet smoke and conversation in the night air.

After their brief stay in Tianjin, provisions were made for Grant to travel by river and canal to Beijing. While Grant was enthusiastic about the individual people he met — especially Li Hongzhang — he was generally unimpressed with China. In a letter to his boyhood friend, recently retired US Admiral Daniel Ammen, Grant described Tianjin as “more populous than Shanghai and more repulsively filthy.”

While Grant was enthusiastic about the individual people he met — especially Li Hongzhang — he was generally unimpressed with China

Grant added, “I have found China and the Chinese much as you have often described it and them: It is not a country nor a people calculated to invite the traveler to a second visit.”

In his public remarks, Grant was far more gracious. While his opinion of China did not improve very much during an unseasonably warm couple of weeks spent in North China, he frequently remarked at the industriousness and cleverness of the Chinese. He also praised the contributions made by Chinese immigrants to America, telling Li Hongzhang: “I do not know what the Pacific coast would be without them. They came to our aid at the time when their aid was invaluable.”

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on Ulysses S. Grant’s 1879 tour of China. Click here for Part 2, looking at Grant’s diplomacy in the territorial disputes between the Qing Empire and Japan.