“Let us drive our chariots through the Helan Pass;

My bold aim is to eat the flesh of the nomads.

Laughing while I thirst for the blood of the Xiongnu,

Wait until we can begin again,

Recovering our old rivers and mountains,

And paying homage again in the imperial court.”

General Yue, tell us how you really feel.

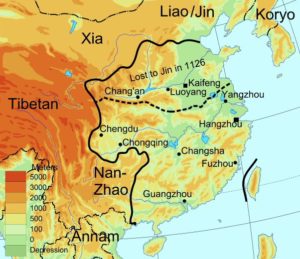

875 years ago today (January 27, 1142) the Song Dynasty general Yue Fei was executed in Hangzhou. In Chinese history and myth, Yue Fei is a great patriot, a paragon of loyalty to the state who was betrayed by traitors and collaborationists in the Song court. After Jurchen invaders of the Jin Empire seized North China in 1127, Yue Fei emerged as a rising star in the Song army who argued passionately against those willing to trade peace with the Jurchen for a detente that would mean the partition of China.

After the fall of the north, what was left of the Song court had fled south to their new capital at present-day Hangzhou, and attempted to regroup around the young emperor Song Gaozong. Gaozong’s father and brother had been carted away when the Jurchen sacked the former Song capital at Kaifeng, and the young and inexperienced new emperor soon fell under the control of Qin Gui, one of his father’s former courtiers. Qin Gui had been captured in the sack of Kaifeng but somehow (miraculously, he said, suspiciously thought others) escaped and made his way to Hangzhou to assist the young monarch.

The new emperor faced a choice: accept the fact of Jin control in the north and instead consolidate his shaky state in the south, or take his chances, continue the war against the Jurchen, and fight to regain lost territory and imperial prestige.

Qin Gui advocated appeasement and the emperor was unsure what to do, but this was an easy question for Yue Fei, now in command of his own army. General Yue marshaled his troops in service to the southern court and won an impressive series of victories, beating back the Jin advance southward while also vigorously suppressing groups of bandits and rebels taking advantage of the chaos to rise and challenge Song rule in the south.

The Jurchen would periodically go on the offensive, hoping to pressure the Song court into signing a treaty conceding Jin control of northern China. Yue Fei insisted that not only should the Song keep fighting, but that their armies should take the battle to the Jurchens and advance north. More cautious officials, including Qin Gui, urged the emperor to concentrate on protecting his position in the south and ordered Yue Fei to spend more time suppressing southern rebels rather than antagonizing the Jin Empire.

Yue also did little to help his case at court. The audacity and courage he displayed in battle came across as abrasive and arrogant. He would offer unsolicited advice to the emperor, useful things like “Why haven’t you chosen a successor?” and “The country needs moral leadership right now.”

Yue Fei would offer unsolicited advice to the emperor, helpful things like “Why haven’t you chosen a successor?” and “The country needs moral leadership right now”

Few officials trusted Yue. He was not one of them, and they looked down on Yue’s lack of education. (Yue Fei’s supposed literary tendencies were mostly the stuff of later myth and legend.) Moreover, Song dynastic precedent made it clear that military officials would be subordinate to the civil bureaucracy.

Yue eventually caught a break. In 1140, the Jin launched a major offensive. Through strategy and luck, Yue was able to turn back the attack and press home his advantage, moving north into Jurchen-occupied territory. But even as Yue enjoyed his most significant successes on the battlefield, pushing the Jurchen back and coming close to recapturing the original Song capital at Kaifeng, forces at court began conspiring against him.

In 1142, the Song court took advantage of their recent success on the battlefield to negotiate a peace treaty with the Jin, one that formalized Jurchen control of north China and required the Song to pay tribute to the Jin emperors. Faced with the choice of a war they might not win or a peace struck while the Song had the initiative, Gaozong agreed to peace.

Yue Fei was recalled from the front. Heartbroken at being ordered to hand over hard-won land still wet with the blood of his troops, he withdrew sullenly to the south saying, “My ten years of effort are destroyed in a single day! It is not that I have not been able to fulfill my responsibilities, but that the powerful official Qin Gui truly has deceived his majesty!”

Heartbroken at being ordered to hand over hard-won land still wet with the blood of his troops, he withdrew sullenly to the south saying, “My ten years of effort are destroyed in a single day!”

Yue Fei was accused of insubordination. Some of his fellow generals turned on him to save their own skin, or simply stood idly by as the great hero of the Song was stripped of his ranks and thrown in prison. Just before the end of the Lunar Year, Yue Fei was found dead in his cell, either poisoned or strangled depending on the account, allegedly on the orders of Qin Gui.

Separating fact from legend is always hard in Chinese history, particularly when that figure is one of China’s most famous patriots. Even the florid poem at the top of the post, words which would become fodder for patriotic lyrics down to the 20th century, was likely a latter-day creation and not from the brush of Yue Fei. Whether myth or man, Yue Fei remains a potent symbol of loyalty to the state and resistance against foreign conquest. One popular story is that Yue Fei had the phrase “Serve the country with utmost loyalty” tattooed on his back.

Whether myth or man, Yue Fei remains a potent symbol of loyalty to the state and resistance against foreign conquest

In Chinese historiography, Qin Gui is the villain of this story, and retellings of the Yue Fei legend accuse Qin Gui of nefarious dealings with China’s enemies and condemn him as an appeaser and capitulator. Yue blamed Qin Gui, not the emperor, for his misfortune, and today in front of Yue Fei’s tomb in Hangzhou, there are two iron statues of Qin and his wife. Visitors to the tomb spit and curse at the statues, punishment for Qin Gui’s treachery and cowardice.

Historian James T.C. Liu, however, has argued that the Gaozong emperor must have been more than a little complicit in the Yue Fei debacle. Gaozong feared the Jin might install his brother, still in Jurchen captivity, as a puppet ruler in the north, weakening Gaozong’s legitimacy. Gaozong also seemed quite content to be the ruler of Jiangnan (south of the river) and was unwilling to risk losing power, preferring to keep his armies in the south consolidating his rule.

Yue Fei was both a patriot and a tragic figure. His devotion to an ideal, and his loyalty to a flawed monarch, ultimately sealed his fate 875 years ago on this day.

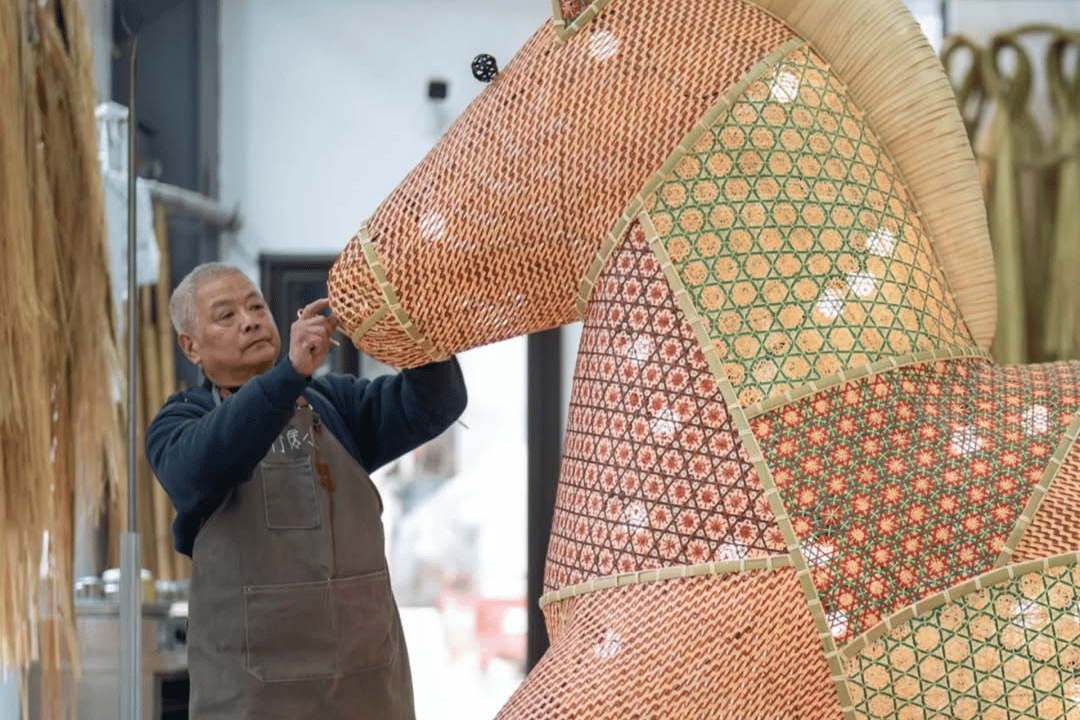

Cover image: Wikipedia