Yinuo Li is director of the China Country Office for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, where she oversees a team that works with China’s public, private, and nonprofit sectors to address key domestic and global health, development, and policy issues. This article has been republished from the collection Get Smart on China with permission.

It sounds like the plot of an Indiana Jones movie: a top-secret military project where a select team of scientists pores over an age-old text, searching for ancient wisdom that could help to eradicate a disease that has blighted humankind for millennia… But this isn’t a Spielberg screenplay, this is the remarkable story of how China is on the verge of eliminating malaria within its own borders and how it can help the world to eradicate the disease for good.

Our story begins in 1967, a year into the Cultural Revolution. Just over China’s southern border, the Vietnam War was raging. At the request of Ho Chi Minh, leader of communist North Vietnam, whose troops were struck down by a drug-resistant form of malaria, Chairman Mao created Project 523, a secret drug discovery unit tasked with finding a treatment for the disease.

Tu Youyou (via SCMP)

Leading the 500 scientists was a female medical researcher, Tu Youyou, who turned to traditional Chinese medicine in her search for a treatment. Eventually she and her team came across the Handbook of Emergency Prescriptions, written in 340 CE by a Jin Dynasty official called Ge Hong. The text mentioned the use of sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua) as a treatment for malaria. This ancient remedy was put through extensive testing, and in 1971 it was confirmed that sweet wormwood contained an active compound that attacked malaria-causing parasites in the blood. The compound was subsequently named artemisinin. The team spent the next six years working to improve the compound’s clinical efficacy, with Tu volunteering to be the first human subject. The team finally published their findings in 1977. In recognition of her contribution to antimalarial research, Tu Youyou became China’s first female Nobel Prize winner, taking the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2015.

Left: Gong He’s ancient text containing a remedy for malaria; Right: Tu Youyou receiving her Nobel Prize in 2015

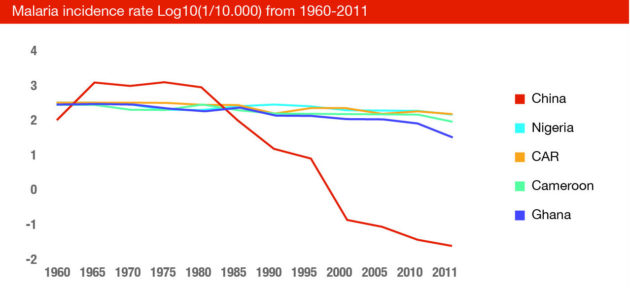

Artemisinin proved to be a turning point in the fight against malaria and was key to China’s own domestic success: in the 1970s almost 25 million cases of malaria were reported in China; today China has almost entirely eliminated the disease domestically. The vast majority of the few cases still found in the country are imported from abroad (97.7% in 2014), particularly endemic countries in the Greater Mekong Subregion.

Government support has always been hugely important in this success. In 2010 it set a target of eliminating malaria in China by 2020. National strategies and targets helped ensure commitment from every relevant body, with officials at all levels held accountable for delivering concrete results. Funding for malaria treatment and prevention has been sustained and continually increased by the government over the years; free anti-malaria drugs are provided for patients, and antimalarial pilot projects are given guaranteed funding. The government has launched numerous public campaigns at the local level to educate about malaria prevention and treatment, particularly targeting the most at-risk populations. The government is also directing its efforts towards poor and marginalized sections of the population, which are especially vulnerable to malaria infection.

China’s early success in fighting malaria was largely thanks to considerable infrastructure investment and growing urbanization, with new roads and drainage helping to wipe out potential mosquito breeding sites. But the country’s rapid decline in malaria rates was sustained over the long-term through the implementation of successful disease-control strategies, such as the innovative 1-3-7 strategy, whereby suspected cases of malaria must be reported by local medical institutions to the China CDC within one day, investigated and classified within the next three days, and an appropriate response be made within the next seven days.

The nationwide malaria surveillance system uses a real-time reporting network system ensuring the early discovery of cases, and allowing the authorities to act swiftly and effectively. Risk assessments anticipating malaria transmission patterns help to provide early warnings of potential transmission hotspots. Effective measures for vector control have also been adopted, including the effective use of insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor residual spraying, clearing mosquito breeding sites, administering biological control measures against the larvae of more resilient mosquito species, and raising public awareness of the importance of preventing mosquito infestation.

There are a few challenges remaining, including the need to further strengthen the surveillance system in order to bridge the last mile of domestic elimination. The most serious challenge, however, is the growing drug-resistance found in the P. falciparum malaria imported from neighboring countries. It’s very much in China’s interests to help these countries to counter this worrying trend. Previously China has supported other developing countries by building anti-malaria centers and donating large amounts of drugs and equipment, but we believe that China can step up and make a much greater contribution to global anti-malaria efforts, particularly in Africa and southeast Asia. With its rich experience, China is in the perfect position to support other developing countries as they move towards elimination and to become a key driver of global eradication by 2040.

Cover image: Chinese anti-malaria poster from 1963 (via US National Library of Medicine)