Earlier this month, Shanghai skateboard brand Avenue & Son touched down in Aranya, Qinhuanghao — along the coast of the Yellow Sea a few hours’ drive from Beijing — to host one of Asia’s most intriguing skateboard competitions. The 2024 edition of Grand Masters (GM) gathered together both professional athletes and rising rookies from all over the Asia Pacific. With leading Chinese DJs setting the scene, enthusiastic crowds, internationally-respected judges, and, best of all, an Olympic standard skate park, for competitors Grand Masters offered an experience unlike any other.

Bringing together a diverse group of 110 skaters from 10 countries, this year’s Grand Masters not only presented a snapshot of Chinese skate culture in the build-up to the Paris Olympics — where skateboarding will feature for the second time — but also a chance for skateboarders from around Asia to connect. When asked about what creates a skateboarding culture, Jasper Dohrs, a skater based in Thailand, explained why he believes a region’s infrastructure matters a lot. “In Thailand, the government isn’t really backing skateboarding. There’s not many public facilities so there’s a lot of skateboarding DIY, making their own skate parks, and that kind of changes the style, mainly street style with tighter transition. There’s no bowl [skate park] like this.”

Right beside the Aranya skate park where Grand Masters was taking place, local children watched the competition and practiced skateboarding with their families. The sight of a five-year-old boy on a board caught my attention. I was curious why he would start skateboarding at such a young age, so I went to chat with his granddad, who was patiently directing him on the side. “He just likes it,” he said to me. “He also plays tennis, but right now he spends a lot of time skateboarding. He’s definitely influenced by his dad who used to skate, but skateboarding’s rising popularity especially after the last Olympics is for sure a reason.”

Having first emerged out of California’s countercultural surf scene in the mid-twentieth century, there’s long been a tension within skateboarding between gritty street skating and professionalized competitions. Regardless of where the soul of the sport lies, it’s undeniable that public consciousness of skateboarding in China is growing as Chinese skaters continue to score high in international events. In the 2022 Hangzhou Asian Games, 14-year-old skater Cui Chenxi from Shandong won first place in women’s skateboarding. She also finished 8th in the 2023 World Skateboarding Championship.

Cui, however, is not China’s only super-young, super-distinguished professional skater. Zheng Haohao, aged 11, has won multiple gold medals in the women’s category of regional and national championships. Both Cui and Zheng will be representing China in the upcoming Paris Olympics.

The success of China’s national skateboarding team as well as the rising interest in skateboarding across the public shows the opportunity for street culture to also widen its influence, but not all street-skaters are confident that it will work out. Gao Qiankun (高乾坤), otherwise known as Kunkun (坤坤), part of the strong Shanghai contingent at this year’s Grand Masters, feels that there are many disparities between both Chinese street-skateboarding and Western street culture, and professional skateboarding.

“Chinese and Western street-skateboarding are definitely not the same because of our upbringings. In China, there were many restrictions growing up where parents don’t want their kids to be in a street culture. This has to do with the education we received as well. Many of us learned how to skateboard much later on. There was also a lack of opportunities and resources to compete in contests like GM at the start. But we’ve always been trying to skate our own feelings and styles. I think there is a unique street culture in China and skaters have their thoughts about how to push it forward. We’re not trying to just copy Western street culture.”

When asked about the differences between street and professional skateboarding, Kunkun expressed mixed feelings.

“I think that skateboarding can be a competitive sport, but skateboarding [as a professional sport] is a different branch from street-skateboarding. Street-skateboarders like me skate for a special sense of joy and a feeling of excitement. Of course, it does help the street culture as the sport becomes more and more well-known, but the extent of it is limited. I mean we have our own way of skating and we don’t need others to advertise it using their methods.”

I was intrigued by his response and asked what he thinks the reason is for such a difference.

“They are different because we are playing the sport for fun, but they are working. There’s a fundamental difference. When you’re working very hard for something, the ideas and thoughts you have about the activity are different from when you’re simply enjoying it, especially when it comes to skateboarding where there’s much more than the technique.”

Nonetheless, one thing that can be observed in both street and professional skateboarding is the goal of building an environment without gender discrimination. Unlike many professional sports in China where both the audience and officials pay much more attention to the men’s category, skateboarding seems to be the opposite. Since skateboarding’s inception in Asian and Olympics games, many of the successes in the field over the past few years have been achieved by young girls such as Cui and Zheng. Their popularity has fueled healthy TV and streaming viewership figures for women’s events.

Back at this year’s Grand Masters at Aranya, not only were there many girls participating in events, but the differences between skaters’ backgrounds were acknowledged and celebrated. As the bowl contest got started the host announced “Our bowl style skateboarding contest welcomes everyone. Men, women, elders, and kids. Let me hear some cheers for the girls here today!”

Over the past few decades, Chinese street culture has experienced a dynamic shift from initially imitating Western urban culture to seeking its own idiosyncratic style. Since its early days in the late 1980s, Chinese skateboarding has had a close relationship with other youth subcultures, from hip hop to graffiti and avant-garde fashion. Today, it still is driving the movement forward, inspiring everything from rap songs to streetwear, while also putting down roots and gradually evolving into a distinctly Chinese form of skate culture.

Though more street-oriented skaters may be doubtful, skateboarding’s admission into the Asian Games and Olympics has led it into a new role that could change the status quo of the Chinese sport scene. Even if skateboarding might be drifting slightly away from its original ethos, right now it has a chance to bridge the gap between street culture and the more formalized Chinese sports scene.

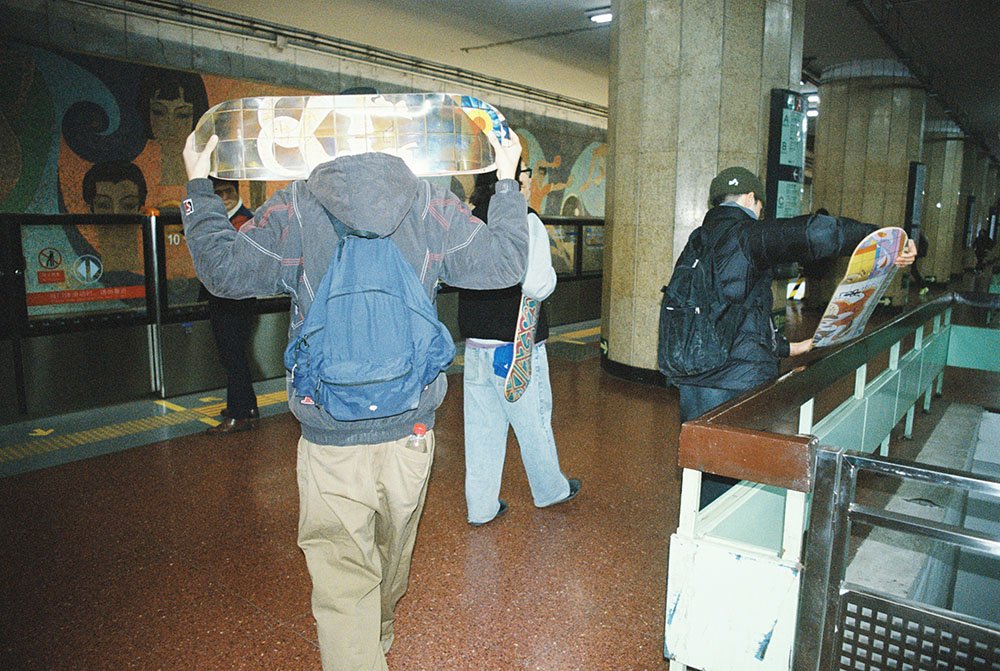

Banner image by Haedi Yue.