China has seen one of the fastest urbanization periods in human history. Its population of city dwellers had swelled from 13% in 1950 to over 60% by the end of 2019, the latter representing an estimated 800 million plus people. As a result, its wilderness is fast disappearing — and due to its link to natural resources and a healthy environment, becoming all the more vital to protect.

That is why a team of Chinese scientists made it their mission to map the last remaining pockets of wilderness within the country — using data from people’s cellphones.

WeChat in the Wild

Researchers at Tsinghua University’s Beijing City Lab utilized location-based services (LBS) data from some of the country’s most widely-used social applications — including messaging app WeChat — to map areas of potential wilderness in China.

Smartphone usage in China is currently the highest in the world, outstripping second-place India by more than 500 million active users in 2019. Of the smartphone apps available to them, WeChat is the most popular in China at 1.17 billion active users, and is so deeply ingrained into modern life that it is nearly impossible to delete.

Related:

Why We Can’t #DeleteWeChatOnline privacy issues continue to dominate headlines in the West following the Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal. But a similar boycott of WeChat is unlikely to emerge in China any time soonArticle Apr 15, 2018

Why We Can’t #DeleteWeChatOnline privacy issues continue to dominate headlines in the West following the Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal. But a similar boycott of WeChat is unlikely to emerge in China any time soonArticle Apr 15, 2018

Due to their apps’ ubiquity, the two researchers behind the project felt that the data from Chinese tech giant Tencent — which owns WeChat — could present perhaps the most accurate representation of human activity throughout all of mainland China.

“We already had the data,” explains Long Ying, research professor and founder of Beijing City Lab. Together with Ma Shuang, currently Project Assistant Professor at the University of Tokyo, Long led and co-authored the study published in 2019.

The logic is that if a Tencent app makes a location request, people are present in the area. By that same logic, large swaths of land with little to no location requests could mean that these areas are potentially wilderness. In order to map this hypothesis out, the scientists divided all of mainland China into a grid of one-kilometer squares, and over the month of February 2016, tagged areas that had less than one location request per day from each square — or fewer than 29 location requests for the whole month — as potentially having wilderness.

Where the Wild Things Are

Though this is the first project in the world to employ LBS data — an increasingly reliable indicator of human activity especially in China, as cellphone service becomes more widely available — equally ambitious attempts have been made to map China’s remaining wilderness in recent years.

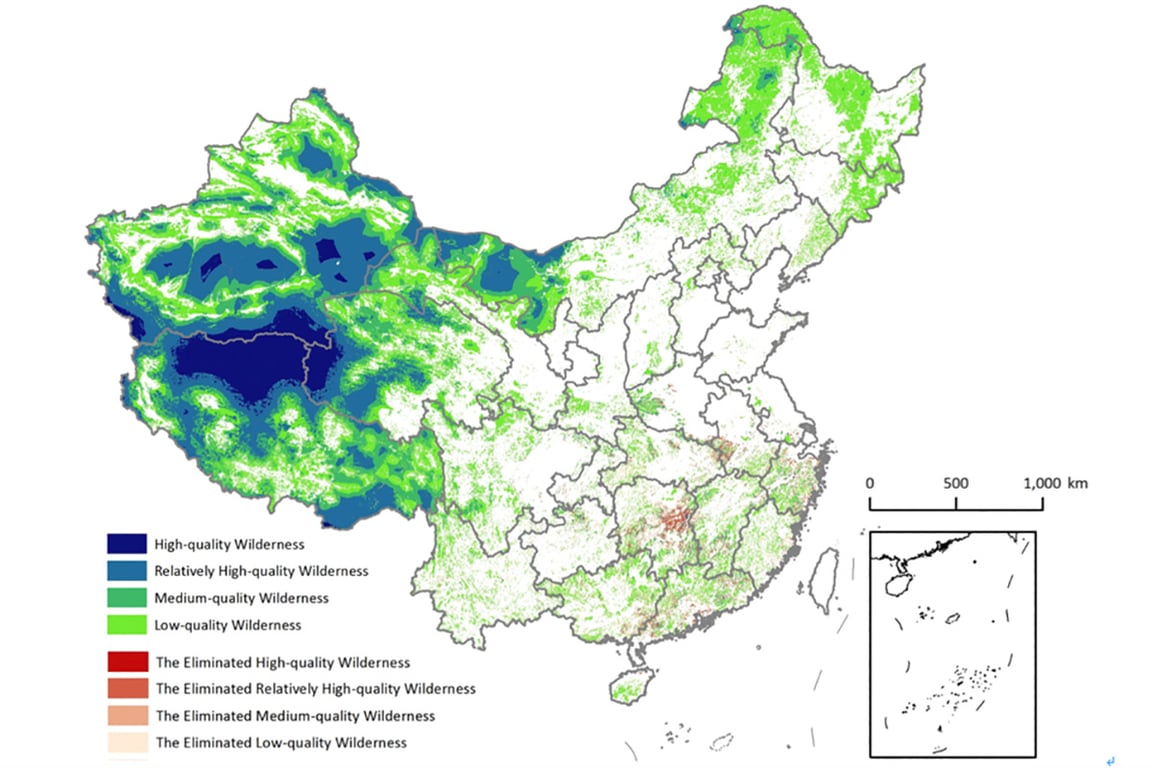

In 2017, researchers Cao Yue, Yang Rui, Long Ying, and Steve Carver set out to document China’s wilderness using the multi-criteria evaluation (MCE) approach to define and grade wilderness.

This approach determines an area’s remoteness from settlements, remoteness from vehicular access, biophysical naturalness (a lack of disturbance by modern society), and apparent naturalness (a lack of modern facilities). From this, Cao and his colleagues derived the Chinese Wilderness Index, which was then used to grade the wilderness quality of different areas on a grid of one-kilometer squares.

But the problem with MCE, says Ma, is that it’s “subjective,” relying heavily on researchers’ judgment to assess remoteness and naturalness. She adds that LBS data is more objective in the sense that it directly reflects human mobility based on how many location requests there are.

“Our use of Tencent data is intended to expand on MCE methods,” Ma explains. The paper combines two different aspects — MCE for ecological, and LBS data for observed wilderness — to create a more comprehensive map of China’s wilderness.

Ma and Long’s map of potential wilderness in China

Why Mapping Matters

Wilderness mapping is perhaps most valuable for wildlife conservation because it gives policy planners an overview of which areas might require more protection.

China has over 11,800 protected areas to date, which make up almost 20 percent of its land mass. These areas are categorized as national parks, nature reserves, wetland parks, and so on, that each have their own ecological protection schemes.

In their paper, Ma and Long evaluated the wilderness percentage of existing nature reserves, in the hope that policymakers can use the data to outline better conservation policies for nature reserves that require more protection, or identify new potential nature reserves. The team also found that nature reserves in western parts of China are better protected — i.e. have more “high grade wilderness” — than nature reserves in the more populated east.

For example, Ma and Long found that Rongcheng Swan Nature Reserve in eastern China’s Shandong province only had a wilderness percentage of 23.6%, whereas Qiangtang Nature Reserve, which stretches from the Tibetan plateau in Qinghai into Xinjiang, scored 99.3%.

Though China has been building up its protected areas over the past 60 years and has implemented a variety of different sustainability programs, Ma and Long’s study provides an avenue for policymakers to focus on the conservation and management of wilderness specifically.

In addition, the Chinese government has spent more than 378.5 billion USD on improving land sustainability since 1998. It has also taken active steps to conserve biodiversity, the most notable example being the research and breeding centers for endangered giant pandas in Chengdu. In recent years, researchers have also started to increasingly focus on conservation and sustainability, sometimes also crossing disciplinary lines to make protected area management recommendations.

Though these measures may not seem relevant to wilderness preservation at first glance, such efforts can have a positive impact on the conservation of wilderness. Improving land sustainability, for example, preserves natural ecosystems, which may in turn help preserve the wilderness of an area.

Aside from policymakers, Long says that their map has also been used by ordinary people. He explains that an American tourist had recently contacted the team about their map, having wanted to take photos of China’s wilderness.

“Generally, more people are paying attention to wilderness [these days],” Ma observes.

Related:

“The speed of the engine spinning”: WildChina Founder Zhang Mei on China’s Shifting Tourist LandscapeArticle Sep 13, 2017

“The speed of the engine spinning”: WildChina Founder Zhang Mei on China’s Shifting Tourist LandscapeArticle Sep 13, 2017

Protecting wilderness not only protects natural resources, such as clean air and fresh water, but also provides recreational spaces for people to take part in. For Long, one of the reasons he conducted this study was because he personally enjoys outdoor activities such as hiking, and therefore understands the importance of being able to do so in places untouched by human activity.

Conservation and Coexistence

With China’s rapid urbanization, conservation work may become threatened, as seen by the diminishing percentage of wilderness across nature reserves.

But Ma and Long firmly believe that urban development can coexist with wilderness conservation, as long as proper support schemes are in place. Long’s Beijing City Lab focuses on just that — by studying the capital city using different disciplines, researchers at the lab aim to produce a “science of cities” that will make urban development sustainable.

Related:

Meet the Architect Whose Revolutionary “Sponge Cities” are Helping Combat Climate ChangeDr. Yu Kongjian and his “sponge city” model have helped change how we think of landscape architecture but also seen him branded a “US spy” by someArticle May 28, 2020

Meet the Architect Whose Revolutionary “Sponge Cities” are Helping Combat Climate ChangeDr. Yu Kongjian and his “sponge city” model have helped change how we think of landscape architecture but also seen him branded a “US spy” by someArticle May 28, 2020

The lab is currently working with the Tencent Research Institute and Tencent Cloud on WeSpace, a project to develop future urban spaces sustainably by integrating smart technologies such as artificial intelligence. “Technology and nature are both important for future societies,” says Long. “We must embrace both.”

While China’s rate of urbanization seem unlikely to slow in the short-term, it must go hand in hand with conservation of natural spaces in order to ensure long-term sustainability. Achieving this balance requires the cooperation of multiple parties — researchers, policymakers, and citizens alike.

Header image: Namcha Barwa, a mountain in the Tibetan Himalayas

All images: courtesy Beijing City Lab