Building China is a monthly series on RADII in which Lauren Teixeira examines China’s built environment, placing some of the features of Chinese architecture into their socio-political context.

In the previous Building China, we established that the superblock — an enormous gated development of residential towers enclosed on four sides by arterial roads — is the basic unit of Reform-era urban development. I argued in my column that superblocks are a fundamentally bad mode of development because of the way in which they induce car dependence and damage community. Furthermore, they enact socioeconomic segregation in that they necessarily sort residents by income.

Toward the end of my piece I mentioned that in response to this issue, Western planners led by new Peter Calthorpe have prescribed a New Urbanist solution for China of cutting down block size to make walkable and mixed use, mixed income neighborhoods.

Building China: Rise of the SuperblockHow China came to repeat the urban development mistakes of the US and Europe, resulting in colossal building projects and car-centric livingArticle Mar 04, 2019

Building China: Rise of the SuperblockHow China came to repeat the urban development mistakes of the US and Europe, resulting in colossal building projects and car-centric livingArticle Mar 04, 2019

But will such an approach work in the Chinese context? A number of planning scholars including but not limited to Fulong Wu, Youqin Huang and Steven Gajer (all of whom I draw heavily from in this article) have treated the gated superblock as the logical evolution of Chinese built form starting with the enclosed courtyard (四合院 siheyuan) and going through the lanehouses (里弄 lilong) and work unit compounds (单位 danwei).

Are superblocks actually a culturally Chinese form, more so than they are in the Europe or the US? The scholars I just mentioned seem to think so, and Gajer has argued that New Urbanism solutions are inappropriate for the superblock because of the cultural sympathy for this form which is “consistent with cultural values of security and collectivism.”

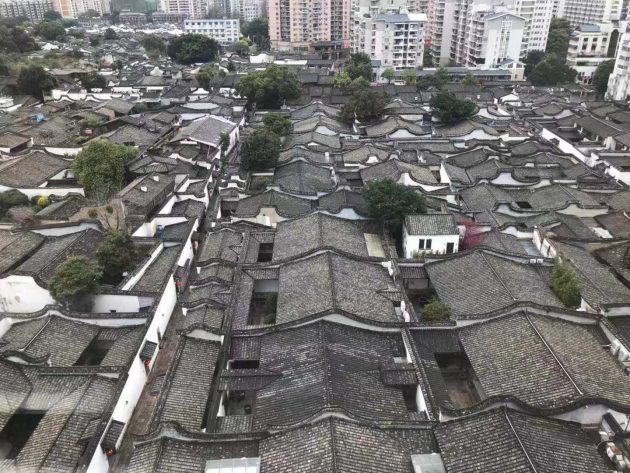

Looking over the alleyways, lanes, and courtyards of the “Three Lanes Seven Alleys” district of Fuzhou

In order to answer this question it will help to go through the history of gating and enclosure in China. Very broadly, it is true that enclosure has always been a characteristic of the Chinese built environment.

The basic unit of Chinese settlement is the courtyard house, which consists of four buildings (although sometimes three) surrounding an open space. Of course, most Chinese peasants did not have the resources for a courtyard house, instead dwelling in a single-room hut. But it’s true that the ideal form was introverted rather than street facing. Some people who study this issue have explained the Chinese preference for the courtyard home as a reflection of Daoist principles about the entity and void. Personally I will refrain from speculation — but it is pretty incredible that Chinese started living in courtyard houses several thousand years ago and that practice remained pretty much unchanged up until the fall of the Qing dynasty.

The Ancient Chinese City

Made up of many adjacent courtyard homes, the ancient Chinese city was cellular in form. Residents were enclosed not only at the level of the home but at the level of the ward or fang, which was walled and gated along the surrounding arterial road (see below image). Under the jiefang system, which was instituted as early as the Shang dynasty (which followed the supposed “first dynasty”, the Xia c. 2070–c. 1600 bce), city residents lived in a fang with people of the same or similar occupation.

Unlike the gated superblock, however, the fang was not socioeconomically homogenous as merchants and artisans of varying degrees of wealth all lived in the same ward. The jiefang system was, above all, a method of political control. The walls existed less to keep undesirables out than to keep residents in: residents had to obey a strict curfew and were not allowed to leave the fang at night — a method, presumably, of maintaining social stability.

The example par excellence of the cellular city is Tang dynasty Chang’an (now Xi’an), which was rigidly segregated into 108 wards (see below). This physical “unit-ization” also enabled the implementation of the baojia system, which divided the population into units of 10 households or bao and was used to efficiently collect taxes, draft men into the army, and generally maintain surveillance.

Tang dynasty Chang’an (photo: chaz.org)

Projection of the upperleft hand corner of Yongning Ward of Tang dynasty Chang’an. Notice the arterial roads enclosing the ward to the west and north (source: chaz.org)

Shanghai Lilong

Arising out of industrialization in treaty port Shanghai, lilong or lane housing was the first significant departure from the landscape of courtyard homes and walled wards that had dominated Chinese urban history. The lilong shared some similarities with fang: the entrance to the lilong neighborhood was typically gated at the edge facing the arterial road. While people did not live in courtyard homes, the tributary lanes along the main lane did serve as a communal space where people would do washing and cooking.

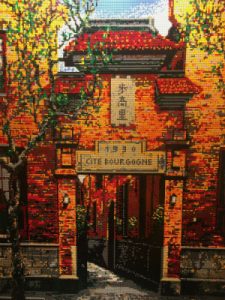

Shanghai’s shikumen are so iconic, one key example has even been rendered in LEGO

Like the fang, the lilong neighborhood contained a fairly high level of economic heterogeneity. Originally intended for a single working class (or in fancier neighborhoods, middle class) family, by the turn of the century Shanghai shikumen (literally “stone gate”, a common feature of lilong architecture and a term often used to refer to lilong that incorporated European architectural features) were being subdivided and rented out to many families and individuals. The small space between the first and second floor (tingzijian), for example, was famously the favored living spot of bohemian intellectuals and literati in the Shanghai of the 1920s and 30s.

For a taste of cramped but sociable pre-Liberation shikumen life I highly recommend the 1949 film Crows and Sparrows, made on the eve of the Communist victory, which tells the story of a diverse group of shikumen tenants who must band together to resist their evil Nationalist landlord (it becomes a propaganda film toward the end but it’s still a great depiction of lilong life).

Work Unit Compounds (Danwei)

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Communists set to work reshaping the built environment in a manner benefitting a workers republic. By the late 1950s, all housing had been nationalized and allocated either by municipal public housing bureau or by the work-unit (danwei).

Work-unit compounds (danwei xiaoqu) were typically walled and gated, but except in the case of high ranking government and military compounds, the gating wasn’t really to keep people out, but to define the unit and encourage collectivity. In this period the work-unit would encompass not only housing units but also a canteen, a daycare and other facilities. As the residents worked and lived together, the feeling of community within the work-unit compound was strong. For an account of “big-compound culture” (dayuan wenhua) at the highest level I highly recommend Jung Chang’s classic memoir Wild Swans, in which the author recounts what it was like to grow up in a compound for high Party officials in Chengdu.

A compact housing block in modern day Chengdu (Photo by Daisy Chen on Unsplash)

As the Mao era grew more paranoid, the work-unit compound increasingly served as the site and means of surveillance. Residents were monitored not only by the collective’s leaders, but by their neighbors. This played out tragically in the Cultural Revolution as people reported each other for so-called crimes and the utopian collective took a vicious turn.

And I think the legacy of this period is an under-discussed reason behind the desire of so many Chinese to move into superblock developments. As Fulong Wu convincingly shows in a 2005 paper, residents of new commodity housing in the late ’90s and early 2000s relished the opportunity to finally enjoy some anonymity; to know nothing about their neighbors and have their neighbors know nothing about them. Rather than escaping proximity to poor people (as we imagine is the case with gated communities in America), the residents of commodity housing were escaping surveillance.

Worker Unit-style housing (pink buildings in foreground) surrounded by new developments, and a golf course, in Tianjin (© Bonandbon DW | Dreamstime.com)

The anonymizing nature of commodity housing was soon seen as a potential problem by the Chinese government. Almost as soon as the housing market took off in the late ’90s, authorities began efforts to “re-unitize” the Chinese urban landscape. As Huang notes, in 2000 the Beijing government issued an order requiring all residential quarters to be developed with gates. At the same time, local authorities were installing gates, cordons and other forms of physical separation in existing residential communities throughout cities.

The late ’90s and early 2000s also saw the rise of the 社区 shequ as the Ministry of Civil Affairs launched a “community building campaign” in which the city was partitioned into shequ with local Party committee-run community centers at their hearts.

A propaganda poster displayed in a shequ reading “Promote and deepen governance of the shequ; build a high quality and harmonious shequ” (photo: author’s own)

Huang argues that this movement is directly related to the decline of the work-unit compound and the need to re-assert social control at the local level: under the new system, she writes, “residents should now consider shequ as opposed to the danwei the basis of their new collective home. It is clear that the government wants to promote territorial collectives to serve and control its population, when the strong foundation for collectives in previous areas disappears.”

A typical shequ “community center” (photo: author’s own)

As we have seen, the Chinese built environment has indeed always been characterized by gating and enclosure. However, this tendency toward inward-facing gated developments should not be understood solely as an expression of Chinese cultural preferences for security and collectivism. In fact, Chinese people started to gravitate to these developments in part because of their desire to escape the panopticon of the danwei.

The gating of superblock developments is therefore less a reflection of a cultural desire to be insulated than a reflection of the Chinese government’s desire to exercise social control and surveillance through the “unitization” of the built environment, much as the rulers of China have done since ancient times.