Building China is a monthly series on RADII in which Lauren Teixeira examines China’s built environment, placing some of the features of Chinese architecture into their socio-political context.

The thing that most struck me about Beijing when I first visited in 2014 was the scale: the roads, buildings, and parks were all enormous. Everything seemed about three times the size as New York City (and in fact Beijing’s population is about three times that of New York). But Beijing didn’t look like New York.

Gazing out to the east from my room on the 30-somethingth floor of a hotel near Olympic Stadium, I thought the city looked more like a huge exurb. Featureless office towers ran along impossibly wide boulevards — highways really — uncrossable without the periodic intervention of pedestrian overpasses. This was not what I had been expecting.

Picture of Beijing taken by the author on her first visit in 2014

Soon enough I learned to think of urban China in terms of two distinct modes. The first, which I experienced in the historic Nanjing neighborhood where I lived, was more along the lines of what I had been expecting: narrow alleys, pedestrians and bicycles, chaotic street life. One of my greatest pleasures was to stroll around my neighborhood at dusk, sampling street food and enjoying the sights and sounds of the evening rush. But stray outside the imprint of the old city walls and that urban China evaporated, replaced abruptly by the kind of scene I observed from the hotel room window in Beijing: residential towers and arterial highways ad infinitum. Walking through these areas was a little bit like the visual equivalent of a hangover: laborious and vaguely headache inducing.

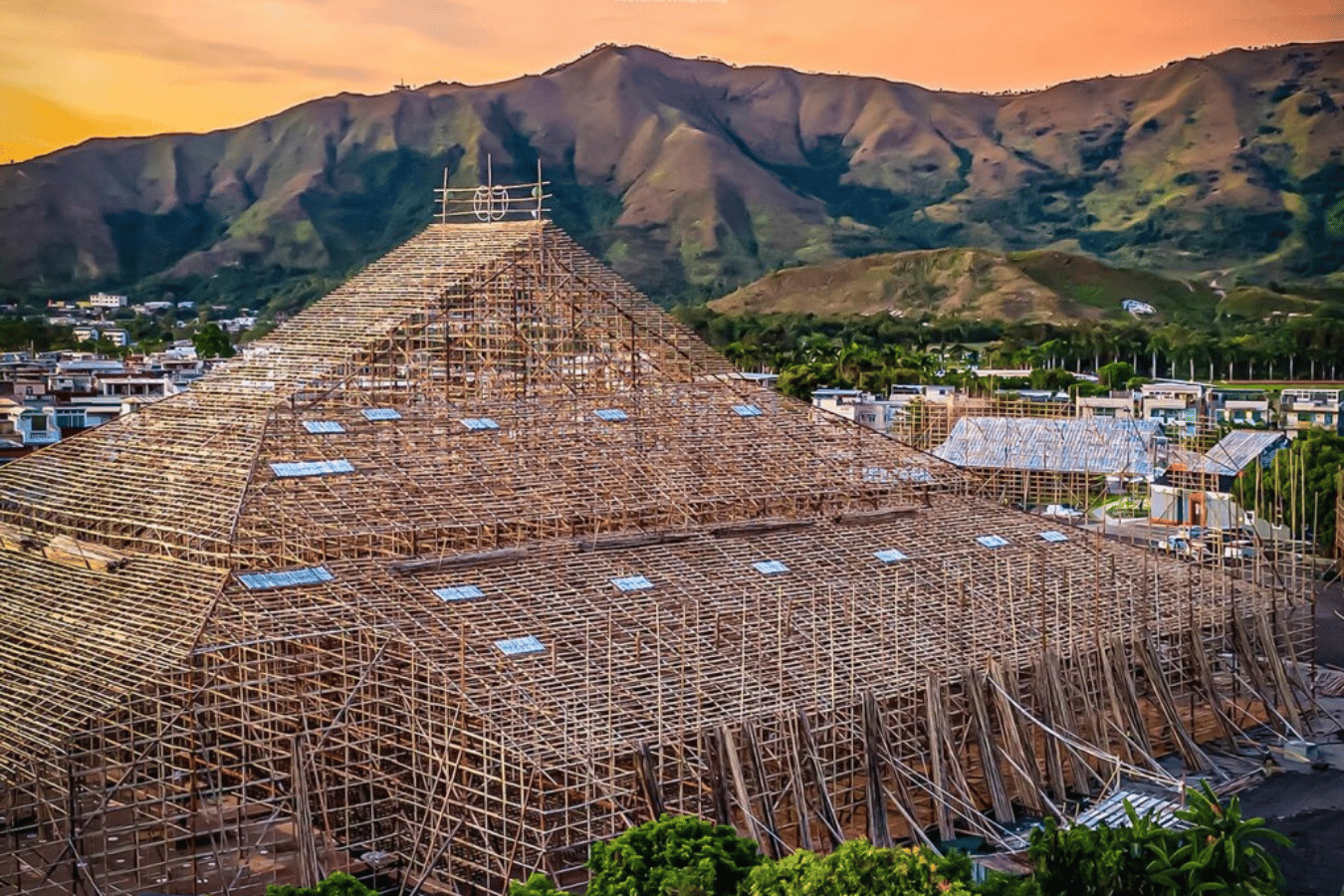

Chinese cities weren’t always like this, of course. The “tombstone urbanism” that we’ve come to accept as an inevitable feature of the modern Chinese city has its roots in the 1990s and the opening up of China’s market economy. While as you have probably guessed I’m not a fan of this mode of urban development, it’s understandable why superblock planning — as it’s called — was initially adopted. With an already critical housing shortage exacerbated by blindingly rapid urbanization, Chinese officials in the 1990s were under pressure to expand the housing supply, and fast. The most expedient way of accomplishing this was to parcel out enormous plots of land to private developers, who quickly filled them with 30-story residential towers. The city planning authorities, meanwhile, obligingly built eight-lane highways between the blocks to service inevitable car traffic.

Shenzhen roads (photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash)

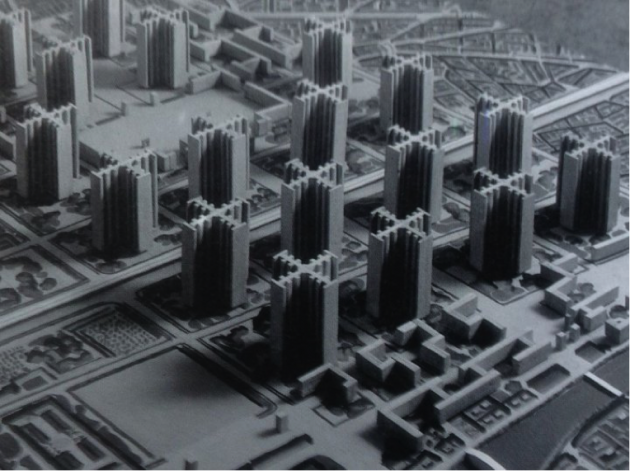

By the time superblock planning was adopted in China, the model was widely discredited in Europe and the US. Urban planning villains like Le Corbusier and Robert Moses had spent the first half of the twentieth century pushing for exactly the kind of model we see in China today, but for reasons of ideology rather than expediency: they saw the “tower in the park” as the very embodiment of order and efficiency, the logical antidote to the grimy and crowded industrial city of the 19th century.

Moses in particular worshipped cars and plowed over as much of New York City with highways as he could. Corbusier and Moses are famously two of the major targets of Jane Jacob’s classic 1960 manifesto against high modernist urban planning, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In the book, Jacobs convincingly showed that the “tower in the park” projects advocated by Corbusier and Moses actually encouraged crime, facilitated social segregation, and destroyed community and neighborhood life.

Le Corbusier’s infamous 1929 “Plan Voisin”

By the 1990s Jacobs’ ideas about mixed use, walkable neighborhoods that encourage social integration and discourage the use of cars had become the mainstream in Western urban planning, advocated for by a group of planners called the New Urbanists (I have my problems with them but we’ll get to that another time). The Chinese government was not unaware of their ideas, either. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Chinese and Western planners — horrified at the cityscapes popping up that resembled something out of Corbusier’s most sinister fantasies — begged the Chinese government to not repeat the mistakes that the West, especially America, had made by building cities around cars and segregating residential and commercial space. In a 2014 column in The Guardian in which she recounts this heartbreaking phenomenon in excruciating detail, Bianca Bosker writes:

Over the past decade and a half, the nation’s developers and government officials have replicated discredited urban planning templates, importing ideas that were tested, failed and long since abandoned in places like Europe and the US. Planning authorities have committed “essentially all the mistakes that have been made in the western world before”, says Yan Song, director of the programme on Chinese cities at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

She recalls how 10 years ago, a delegation of planners from the US convened with Chinese officials, who were then working on eliminating Beijing’s cycle lanes to make room for more cars. “The American planners were saying, ‘Don’t do that, please! We’ve done that, we have made that mistake. Don’t follow us,’” says Song. “But at the time, when you have that kind of modernisation, people love cars – so unfortunately the planners there didn’t listen.”

It’s hard not to grind one’s teeth in frustration when reading about this slow-mo car crash (pardon my metaphor) of an urban planning disaster. It’s tempting, too, to imagine what could have been: what if local officials had learned from America’s mistakes and initiated the kind of mixed use, public transit oriented development that’s cutting edge in the West only now?

I think about this often, and while it’s extremely frustrating, I agree with most people who write about this issue that this alternate reality was probably never a real possibility. One reason for this, hinted at by the planner Yan Song in the above passage, is the symbolic importance of cars and highways. Chinese officials obsessed with projecting a “modern, world-class” facade would of course seek to emulate the American city model, no matter how badly that model has been discredited. For ordinary Chinese people, too, car ownership was a crucial indicator of socioeconomic status (think of the refrain on the Chinese marriage market that men have “a car, a house, and savings”) and driving a car represented individualism and freedom associated with America.

Shanghai roads (photo by Denys Nevozhai on Unsplash)

But an even more important reason behind the continued insistence on superblock planning is the reliance of Chinese city governments on land lease revenue. Since the tax-sharing reform of 1994, cities have been obliged to fork over an enormous percentage of their tax revenue to the central government. In order to generate enough revenue to cover social services and other costs, cities have come to rely heavily on China’s land-lease mechanism that allows the city to rent parcels of land to private developers for a period of 70 years.

Superblock planning therefore was irresistible to Chinese officials, who could quickly expand the housing supply and generate a massive amount of tax revenue in the process. Although it’s changing, it’s still the case that Chinese cities generate an astonishing percentage of their revenue from land leases — more than half by most estimates. (The tax sharing reform is also one of the major factors behind China’s abysmal record when it comes to preserving historic architecture — local officials are eager to lease out the valuable inner city land on which the historic homes lie).

Related:

Photos: Inside the Disappearing Alleyways of Shanghai’s LaoximenArticle May 21, 2018

Photos: Inside the Disappearing Alleyways of Shanghai’s LaoximenArticle May 21, 2018

The effects of superblock development in China have been, quite simply put, disastrous. In 2006 it was estimated that China was building 10 to 15 superblocks per day. Between construction and car usage, superblocks are probably one of the most under-appreciated culprits behind China’s pollution problem: a 2006 study by planners from Berkeley found that 30 percent of China’s CO2 emissions could be directly attributed to superblock development. Essentially, the environmental problems with superblocks are the same as those related to suburbanization in America — when you live in a sprawling, exclusively residential area, you have to drive a car to go anywhere, whether it’s to go to work or go grocery shopping.

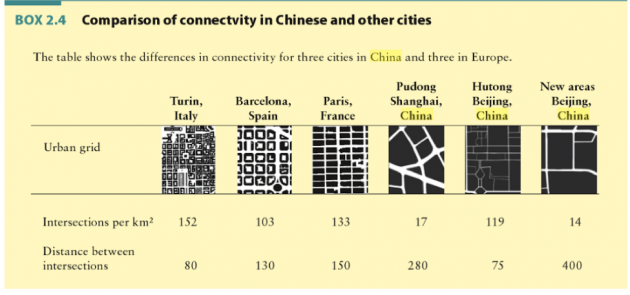

And the average Chinese superblock is really, really big — a World Bank report puts it at anywhere from 400 meters to 800 meters a side. Even the smaller 400 meter/side superblock, the report points out, is equivalent to 11 blocks in London, Manhattan, or Hong Kong, or 64 blocks in Tokyo. Indeed, the New Urbanist Peter Calthorpe has referred to the Chinese model as “high density sprawl” (he’s also called the superblock a “weapon of mass urban destruction.”)

From the World Bank Development Research Center report, “Urban China: Toward Efficient, Inclusive and Sustainable Urbanization”

The Chinese superblock also suffers from another problem associated with American suburbs — segregation. American suburbs, which flourished during the era of “white flight” in the mid century, are a famously racist form of planning which in both indirect (income sorting) and direct (neighborhood covenants) ways allowed whites to live exclusively among other whites of similar socioeconomic status.

Chinese superblocks obviously don’t have the race problem, but as they’re comprised of many identical residential towers they do necessarily sort people according to what level of housing they are able to afford. It’s hard not to believe that gated superblock developments, which nauseatingly often include daycare centers, cram schools and other amenities for residents’ children within the superblock gates, have benefited from the obliteration of social trust in China’s Reform era.

Some people who study this last issue have argued that gated superblocks are actually a logical evolution of the Chinese urban form, consistent with earlier traditions like courtyard housing, lilong (lanehouses) and danwei (work units). I will address this in my next column on gating, enclosure and the Chinese urban form. After that, I’ll finish up this trio of articles with a column on China’s “new urbanism.” Although superblock development is still rampant, China’s highest planning authorities are finally admitting that they’ve made a mistake, and some efforts are now being made to rectify the superblock and redress earlier urban planning sins. But are these reforms too little, too late for the Chinese city?