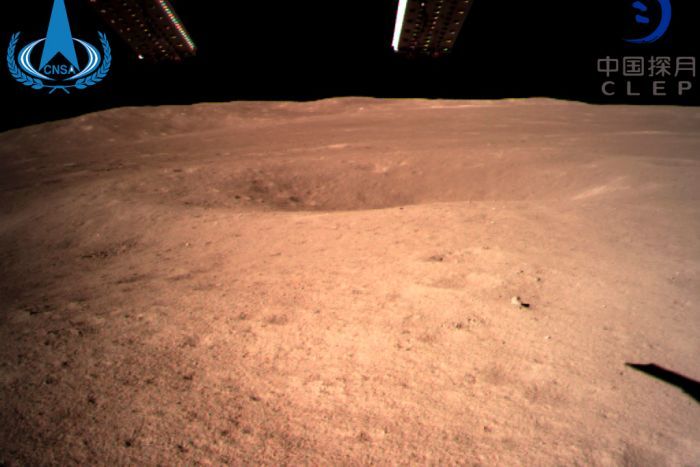

China is aiming high with its lunar exploration program. The upcoming Chang’e-6 mission, slated for 2024, will make history by returning the first samples from the mysterious far side of the moon — but this milestone is just one step in China’s journey to become a major space power by 2030.

The unmanned Chang’e-8 expedition, scheduled for 2028, is taking an international, collaborative approach. The China National Space Administration (CNSA) is inviting partners worldwide to jointly operate explorations on the moon’s surface, allowing other countries to “piggyback” off the mission. The data from these missions will support China’s goal of building a permanent international research station at the moon’s south pole.

These missions signal a shift in space exploration dynamics. China’s open invitation to global partners for Chang’e-8 is a big step forward in advancing space science through cooperation, in an era where lunar activities are no longer the domain of only a few space powers.

The China National Space Administration (CNSA) is offering opportunities for international cooperation on payloads that will piggyback on the country’s Chang’e-8 #LunarExploration mission, slated for launch around 2028, in order to encourage more major original discoveries. pic.twitter.com/Bk59vn5EoJ

— People’s Daily, China (@PDChina) October 3, 2023

China’s bold lunar initiatives are the source of both excitement and controversy. Recently, Chinese scientists may have been getting a bit competitive, or even petty, after India’s Vikram lander claimed to touch down on the moon’s south pole.

Ouyang Ziyuan, the chief scientist of China’s first lunar mission, challenged the claimed landing site of India’s Vikram module, suggesting it fell short of the lunar south pole.

He told the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Science Times newspaper that the landing site of India’s mission “was not at the moon’s south pole, not in the polar region of the moon’s south pole, nor was it ‘near the Antarctic polar region.’”

The region is coveted for potential water ice deposits, making it a high priority for multiple space agencies.

That being said, there’s significant truth to these critiques. Vikram, now frozen in place, landed at a latitude of 69.5 degrees south. While Ouyang’s definition of the moon’s polar region (between 88.5 and 90 degrees) is stricter than NASA’s (anywhere between 80 and 90 degrees), 69.5 degrees definitely falls short of both ranges.

China’s space ambitions are also tied into popular culture, particularly Chinese science fiction — themes of space exploration are particularly appealing to the public imagination in the wake of a sci-fi renaissance initiated by Liu Cixin, author of works like The Three-Body Problem and The Wandering Earth.

With each successive mission, China is rewriting the playbook for space exploration. The upcoming Chang’e-7 rover will scout lunar resources at the south pole, laying groundwork for the International Lunar Research Station in the 2030s.

Cover image via Unsplash