Ask folks in Bangkok or Kuala Lumpur about what they think about durian, and it’s likely they will fall into one of two camps: hate it or love it. However, at the moment in China, it seems the passion outweighs the hate. Viral scenes of crowds queuing for hours to buy premium Malaysian Musang King at exorbitant prices have become both conversation starters and serious business. But the real story isn’t just about fruit. It’s a window into how Chinese tastes are shifting, what that means for Southeast Asia, and why the next export boom may be defined less by volume and more by cultural relevance.

A Durian Love Affair

China is the world’s largest durian market by a considerable margin. In 2024 alone, the country imported durians worth nearly 6.99 billion USD, with volumes reaching 15.6 million tonnes, both figures setting new records and intensifying competition among exporters across Southeast Asia. Thailand remains the largest supplier, but Vietnam and Malaysia have rapidly increased their market shares. What might look like an internet curiosity (think two-hour queues and sold-out shipments) is in fact a clear signal of sustained demand in a market that increasingly values novelty, scarcity, and quality.

A New Challenger Enters the Orchard

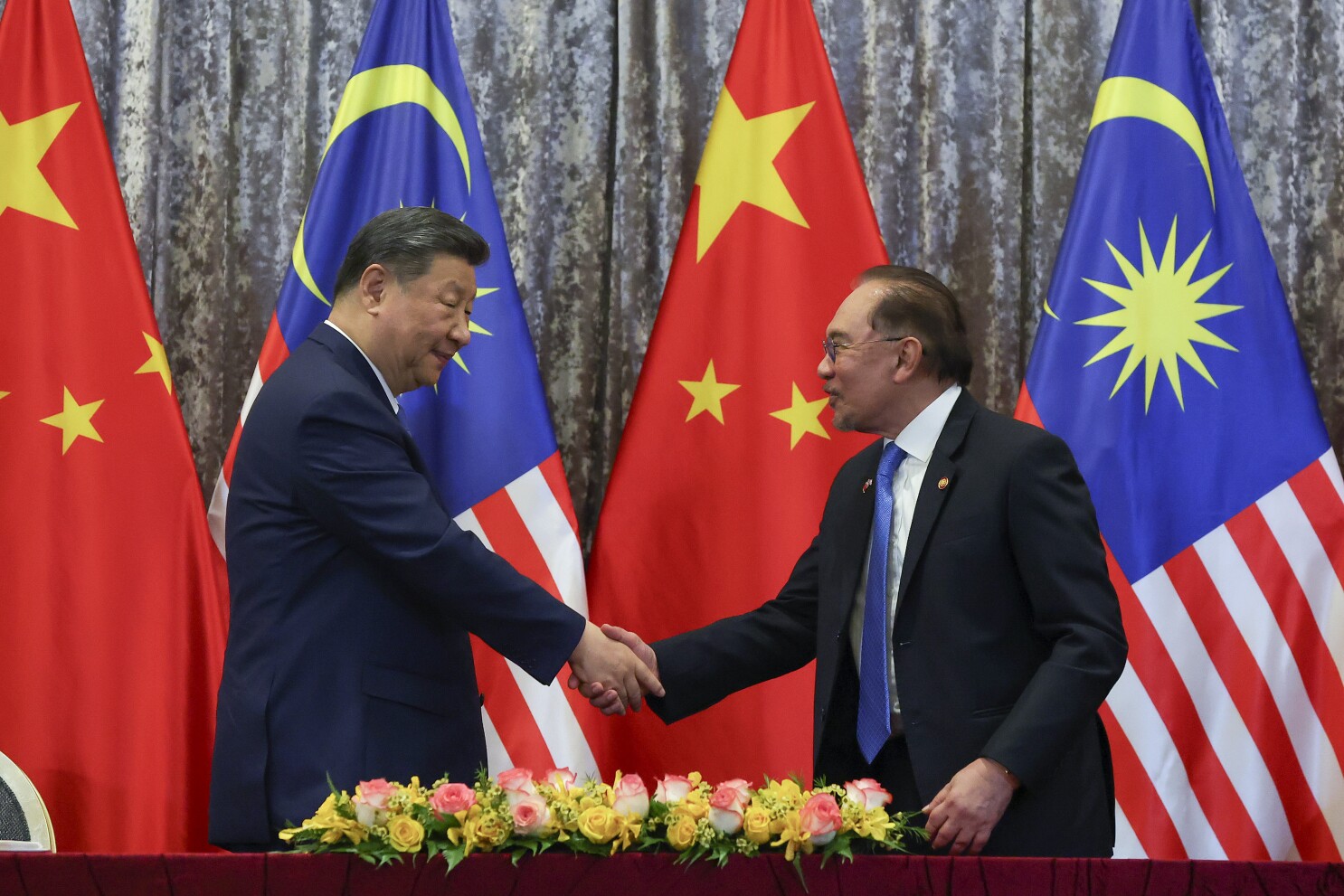

Now, Laos has officially entered the race. In late 2025, China’s General Administration of Customs cleared Laos to begin exporting fresh durians to the Chinese market, as long as shipments comply with local requirements. For Laos, this approval represents more than just agricultural access. It marks entry into one of the world’s most lucrative consumer markets at a time when appetite for the fruit continues to grow.

Part of Laos’ appeal lies in logistics. The China–Laos Railway has dramatically shortened delivery times to southern China, enabling fruit to reach markets faster and fresher while keeping costs down. Combined with relatively cheap land and labor, Laos is emerging as a formidable competitor to established exporters like Malaysia and Thailand—not necessarily by out-branding them, but by undercutting on speed and supply.

Durian Is Just the Start

Yet durian’s popularity points to something larger than agricultural competition. It reflects a broader shift in China’s consumer culture, one increasingly shaped by novelty and lifestyle identity rather than sheer necessity or price sensitivity.

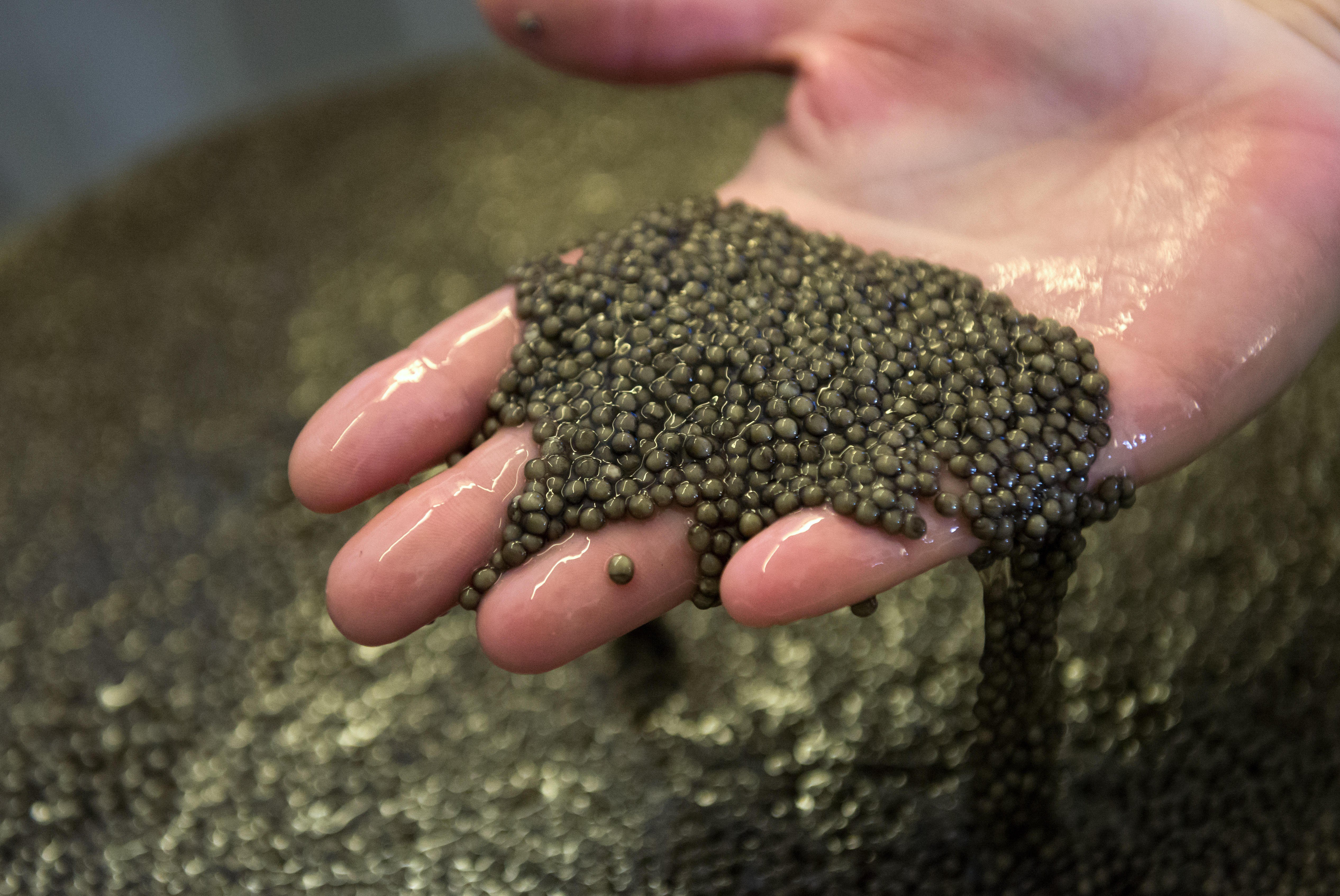

China is no longer just a destination for imported luxury foods; it is becoming a producer in its own right. The country has rapidly expanded production of once-rare items such as caviar, cherries, truffles, macadamia nuts, and even foie gras, with domestic output increasingly catering to Chinese tastes. The aim is not only to achieve self-sufficiency in these categories but also to cultivate a domestic premium food ecosystem that mirrors global markets.

Southeast Asia’s Next Test

For Southeast Asia, this evolving landscape presents both opportunity and pressure. Infrastructure developments like the China–Laos Railway are reshaping how perishable goods move across borders, reducing spoilage and enabling faster market access not only for durians but potentially for other tropical fruits such as mangosteen and longan. At the same time, China’s increasingly strict quality controls have already disrupted certain shipments from the region, underscoring that access to the market now depends as much on standards, traceability, and compliance.

This is where branding begins to matter. Malaysian durians, especially the Musang King, are often positioned as luxury products rather than mass-market staples, a distinction that may help them weather competition from lower-cost producers. Think of it this way: Musang Kings are basically the LVs of the durian world.

Looking Beyond the Fruit

Looking ahead, the next decade could see Southeast Asian exporters widening their focus well beyond durian as China’s appetite for lifestyle-linked and interest-based goods continues to grow. This opens up space for Southeast Asian exports that sit outside traditional commodity lanes. Pet food and accessories, outdoor and fitness equipment, designer toys, collectibles, modest fashion, wellness products, and even niche beauty and personal-care brands are all categories that align with China’s broader shift toward identity-driven spending. Many of these products already circulate through cross-border e-commerce platforms, where Southeast Asian brands can test demand without the scale required by traditional retail.

Perhaps most importantly, cultural relevance will be key. As China builds its own premium industries, simply supplying raw materials or generic goods may no longer be enough. Products that connect with lifestyle, experience, and aspiration are more likely to endure, whether they arrive in the form of fruit, fashion, toys, or pet products.

Cover image via VnExpress International.